Evidence from a decade of International Growth Centre research projects sheds light on the types of research that have policy impact, and when impact is maximised.

Key takeaways

- Co-creation enhances policy impact: Collaborative projects with policymakers are more likely to influence policy without sacrificing academic impact.

- Election timing matters: Research projects that were initiated early in the political term, when policymakers are more receptive, were more likely to have policy impact.

- Institutional affiliation advantage: Researchers from elite institutions can consistently engage in impactful partnerships throughout the political cycle.

Modern development economics has increasingly focused on policy relevance, aiming to identify interventions and innovations that deliver the highest impact on poverty reduction and growth. Yet, empirical scholarship on the research-to-policy pipeline remains limited in the discipline - some exceptions include Hjort et al. (2021), Vivalt and Coville (2023), DellaVigna et al. (2023), Mehmood et al. (2024). What are the design features of projects that achieve policy impact? Who are the researchers conducting these projects? Does policy success come at the cost of academic achievement? These questions are essential for guiding the funding and production of research but remain mostly unexplored due to a lack of data on the policy outcomes of these projects.

To address this issue, I collaborated with the International Growth Centre to build a large dataset of research projects conducted in the field of development economics over the past decade, tracking policy decisions occurring after completion. Using this novel dataset, I explore whether projects designed in partnership with policymakers, in a process often called co-creation, deliver on their promise to achieve policy impact while maintaining academic relevance (Bonargent 2024).

Central to the construction of the dataset is the organisation’s dual mandate to achieve both policy impact and academic performance, along with its commitment to report on these objectives to its main donor. This ensures that funded projects are academic in nature and has led the organisation to invest in a data collection infrastructure to track the uptake of research. This infrastructure relies on country office staff, located in regions where research is funded, and a dedicated team responsible for compiling information on impact. To obtain quantitative variables capturing co-creation and evidence uptake by policymakers, I manually coded thousands of internal records, including project proposals, implementation reports, and data from the monitoring, evaluation, and learning team. The final dataset consists of over 500 research projects initiated between 2009 and 2018, conducted primarily in West, East, and Southern Africa, and South Asia.

Fact 1: Co-creation is associated with higher policy impact

The primary measure of policy impact captures any instances of change in programmatic or operational decisions by local policymakers after project completion, as well as the decision to commission additional research. Policymakers in the sample are mostly government actors and public administrators, but also include some social enterprises and non-governmental organisations operating at the national level.

Active engagement in the design and implementation of a research project by a policymaker can take many forms, including shaping research questions, commissioning studies aimed at addressing specific policy challenges, facilitating access to internal data, building data management infrastructures, and, in the context of randomised experiments, participating in the design and delivery of interventions.

Designing and implementing a research project with a policymaker increases the likelihood of policy change by 17 to 20 percentage points. This magnitude is substantial when compared to the mere 3% of non-partnership projects that resulted in evidence uptake. The relationship between co-creation and evidence uptake is homogenous across different characteristics of the research teams, including career stage and local affiliation.

Importantly, these results are not driven by a sorting of policymakers into policy-oriented projects of limited academic value. The publication rates are similar between projects implemented in partnership and those conducted by researchers alone, across different journal rankings. The relationship between partnerships and evidence uptake is in fact stronger for projects that produced published articles.

While the findings do not rule out the possibility that collaborations with policymakers could negatively influence research outcomes—the sample comprises projects chosen for their academic value and likely omits those that are entirely policy-oriented—they do highlight the existence of a class of projects that achieve both academic and policy impact through the process of co-creation.

Fact 2: The election cycle affects the timing and quality of co-created projects

While working with policymakers improves evidence uptake, it also makes academics dependent on their availability and willingness to collaborate, and subjects them to the influence of local political events. I explore this dynamic by using the election cycle in the country of implementation to capture the intensity of political constraints faced by researchers seeking to engage with local policymakers.

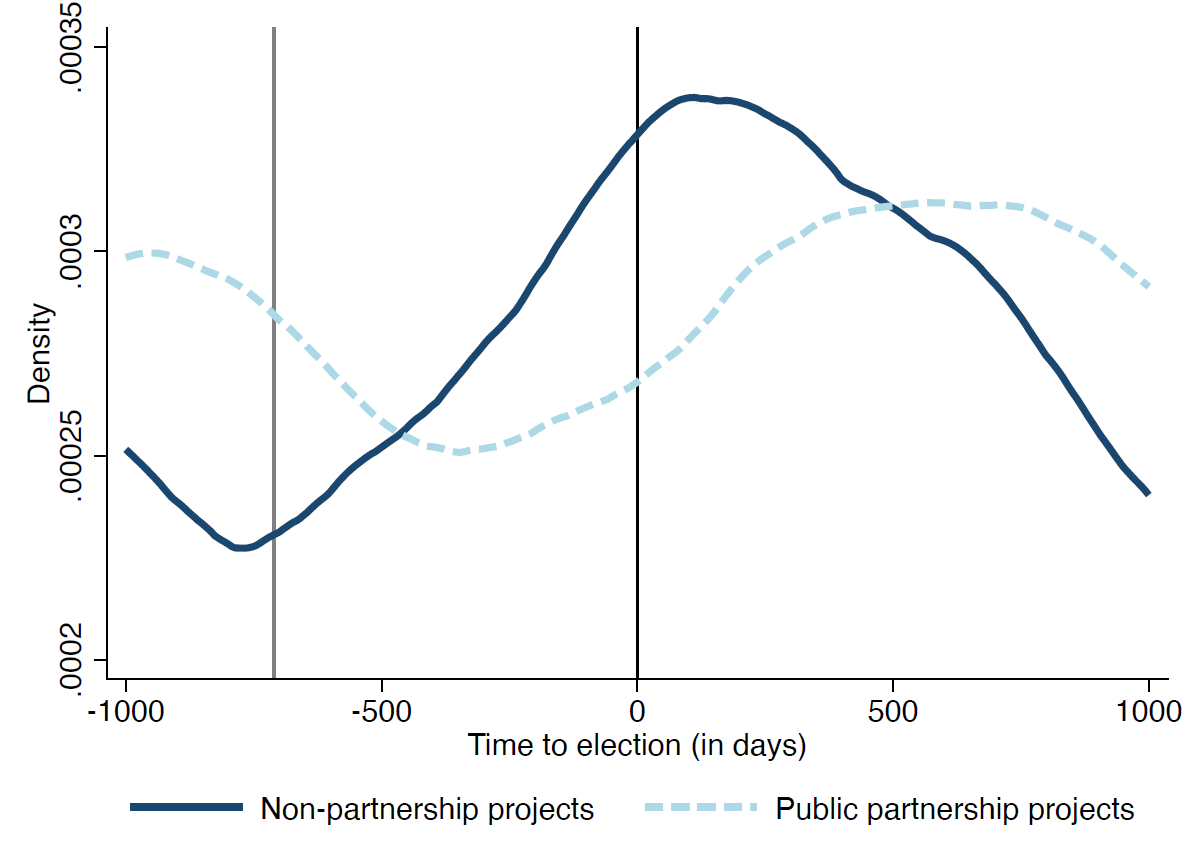

Figure 1: Seasonality of partnership formation around the election cycle

Note: This figure displays the kernel density estimates for the duration (in days) between two key dates: the deadline of the funding call for which a proposal is submitted, and the nearest general election in the country where the research project is implemented. The estimates are shown separately for projects co-created with public policymakers and for those not co-created. For this figure, 'public policymakers' are defined as governments, public administrations, and private sector institutions that are mandated to deliver public services through public-private partnerships.

Projects funded within two years of an election are 10 percentage points less likely to be co-created. To test that these results are driven by policymakers’ willingness to engage rather than to other factors coinciding with elections, I consider a subsample of projects implemented in countries with relatively stronger democratic institutions, as captured by the Polity V democracy index. The coefficient increases from 10 to 15 percentage points, supporting the notion that political constraints account for the observed seasonality of partnership formation.

The election cycle also affects the policy outcomes of co-created projects: these projects are 15 percentage points less likely to result in policy change when initiated in the two years prior to an election compared to those started earlier in the term. The same result is obtained when considering only elections without party transitions, suggesting that this decrease is due to the nature and quality of the projects rather than new incumbents systematically dismissing efforts from previous administrations.

Fact 3: Researchers’ affiliation determines exposure to political constraints

The rank of the researcher’s affiliated institution plays an important role in mitigating the effects of the political cycle. Using RePEC rankings from 2009, I identify elite institutions (top 15 economics departments) and mid-tier institutions (remaining top 200 economics institutions).

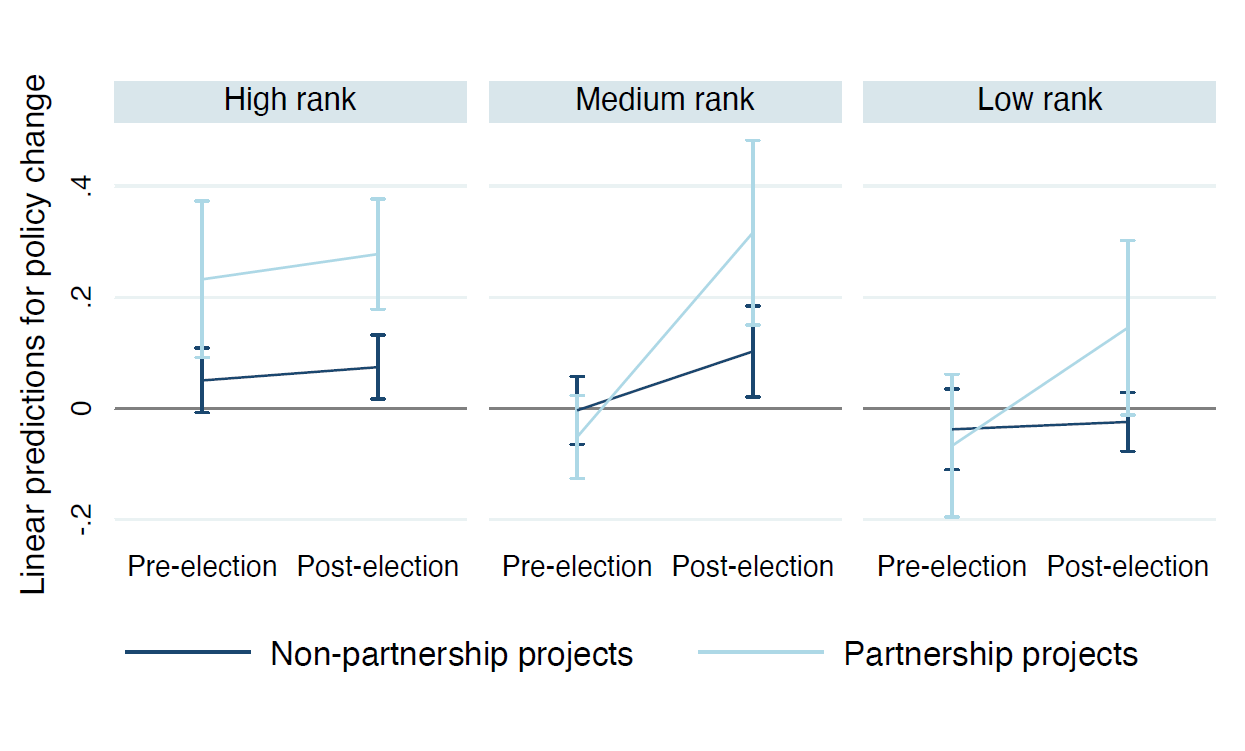

Figure 2: Quality of partnership around the election cycle by institution rank

Note: This figure illustrates the linear predictions from an OLS regression of 'Observed Policy Change' on the pre-election period (i.e., projects funded within two years of an election), including controls for research team characteristics and project scale, and election-specific fixed effects. Predictions are shown by the highest institution rank within the project team for both pre- and post-election periods. Estimates are presented with 95% confidence intervals, with robust standard errors.

Researchers from elite institutions are generally unaffected by elections: they have the capacity to establish partnerships and consistently achieve policy impact throughout the cycle. Those from mid-tier institutions engage in partnerships both before and after elections, yet it is only the post-election collaborations that yield a high rate of evidence uptake. Researchers from other institutions find themselves sidelined during the pre-election phase but are able to form effective partnerships after the elections.

Why do researchers from top institutions have such an advantage? According to qualitative evidence from the IGC’s records, it is likely due to their greater ability to mobilise funding. First, they lead projects with larger budgets and can afford to hire staff to work directly within governmental structures. These staff members can substitute their efforts for those of their counterparts during times when attention is diverted to political objectives. These projects often result in repeated "embedded" partnerships that grant significant autonomy to academics.

Second, policymakers might choose to work with top academics to leverage their networks among institutional donors: many projects in the sample that resulted in policy change were characterised by continued support from research teams post-completion, including fundraising for scaling-up interventions.

Key takeaways for policymakers and researchers

Partnering with policymakers to design and implement research projects can significantly increase policy impact without compromising academic success. However, such collaboration opportunities can be scarce, particularly for researchers not affiliated with elite institutions.

For researchers facing political constraints, this study identifies a window of opportunity for co-creation opening early in the term, when policymakers are less focused on political objectives and have more time to engage in policy-relevant research projects.

Are the observed patterns of partnership formation desirable in terms of achieving the best possible policy outcomes in the country of implementation? Evidence uptake levels for projects initiated in the post-election period are comparable across institutional ranks, suggesting no intrinsic differences in the ability to conduct high-impact projects. Further investigation is needed to determine whether matching between academics and policymakers could be improved through better funding allocation across researchers.

References

Bonargent, A (2024) "Can Research with Policymakers Change the World?"

DellaVigna, S, W Kim, and E Linos (2023), Bottlenecks for Evidence Adoption.

Hjort, J, D Moreira, G Rao and J F Santini (2021), How research affects policy: Experimental evidence from 2,150 brazilian municipalities. American Economic Review, 111(5): 1442-1480.

Mehmood, S, S Naseer and D Chen (2024), "Training Policymakers in Econometrics."

Vivalt, E and A Coville (2023), "How do policymakers update their beliefs?" Journal of Development Economics, 165: 103121.