Removing barriers to internal migration can boost a country’s productivity, albeit modestly and with heterogonous effects on original populations

As is well known, most people in developing countries work in rural areas, primarily in agriculture. Less well known is that the gap between rural/agricultural productivity and urban/manufacturing and services productivity is much larger in developing countries than developed countries. In short, most people in the developing world work in the places where they are least productive. Given these facts, it is natural to ask whether there could be large development gains from encouraging workers to move to productive locations and sectors. We explore this question with data from Indonesia.

Within-country productivity gaps

An important fact when thinking about poverty reduction is the presence of large within-country productivity gaps. One manifestation of this fact is the well-known urban rural productivity gap: within the same country, urban (or non-agricultural) productivity is often two to three times higher than rural productivity (Caselli 2005, Gollin et al. 2014). Observing these gaps naturally leads to a question: is it possible to increase productivity and incomes and to grow out of poverty simply by moving people across space? If so, why is this not happening faster?

Figure 1 shows that the potential for spatial arbitrage extends beyond the usual rural urban example. The figure plots the average wage across different regions in Indonesia. The data, taken from the 2011 SUSENAS survey (National Socio-Economic Survey), show clearly that even within the same country, there are areas with high wages (for example, the eastern parts of Kalimantan, where there is a lot of mining) as well as areas with low wages, such as central Java.

Figure 1 Distribution nominal wages, 2011

In a recent working paper (Bryan and Morten 2018) we ask whether increasing migration would lead to higher aggregate productivity by allowing people to work where they are most productive.

Why do wage gaps exist?

To make progress, we first need to understand why the wage gaps exist in the first place. We can distinguish between exploitable productivity gaps and unexploitable productivity gaps. On one hand, a productivity gap is exploitable if a policy could increase migration and hence productivity. For instance, if potential migrants have high returns but are deterred by the costs associated with movement, for example cultural differences, discrimination against migrants, or high costs of communicating with family at home, then policies that reduce these costs can encourage migration and improve productivity. Similarly, if high productivity locations are characterised by low amenities due to pollution, crime, high home prices or lack of access to public goods, then improving these amenities can lead to increases in productivity.

On the other hand, the gap is not exploitable if it is caused by selection. If cities are more productive because more productive people choose to live in them, then potential migrants will not be as productive as current city dwellers, and encouraging movement through any of the above policies will not increase productivity. Our work seeks to quantify the extent to which spatial productivity gaps are exploitable. We ask: what is the extent of possible productivity gains from the suite of policies that could encourage spatial relocation?

Using data from Indonesia

To address this question, we first present evidence that is consistent with the existence of both exploitable and unexploitable gaps. Using microdata spanning 40 years from Indonesia, we start by showing five facts: (i) people migrate to places that are closer; (ii) within a destination, and controlling for origin differences, those who have come from further away earn a higher wage; (iii) within a destination, those who come from areas with a larger share of their population living in the destination earn lower wages; (iv) within a destination, those who come from areas with a larger share of their population living in the destination earn lower wages, even after controlling for distance; and (v) among those from the same origin, people who move to locations with lower amenities earn higher wages.

Fact (i) is suggestive of a cost to migrating longer distances and suggests a role for policy. Facts (ii) and (iii) are suggestive of selection, and caution that policy probably cannot extract all the productivity gains suggested by a naive interpretation of the urban rural gap. Fact (iv) suggests that the migration cost drives the selection effect meaning that worker sorting may be improved through migration. Finally, fact (vi) suggests that relative amenities matter for worker location choices, implying that policies aimed at improving amenities will affect worker choices.

Making progress on estimating what portion of productivity gaps is exploitable

These facts are interesting, but they are equivocal, they leave caution that selection is important, but do not answer what portion of the spatial productivity gaps is exploitable. To make progress on this question we write down a model that can explain the above facts using the following elements: migration is costly, locations differ in their amenities and productivities, and workers sort into locations according to their comparative advantage. Finally, we allow for general equilibrium effects through a downward sloping labour demand curve, as well as endogenous amenities and agglomeration effects. We then estimate this model using the microdata.

Using this model, we consider the likely impact of several types of policy. The first question we ask is, what would happen to productivity if policies were able to remove all migration costs? Examples of this type of policy might include migration subsidies (Bryan et al. 2014), migrant welcome centres, language training, and road building (Asher and Novosad 2016, Morten and Oliveira 2018). The second counterfactual we consider reduces the dispersion of amenities. Again, this corresponds to the aggregate impacts of a set of possible policies. For example, encouraging home building in high-demand locations (Harari 2017, Hsieh and Moretti 2018), reducing pollution in cities, and providing equal access to schooling and hospitals.

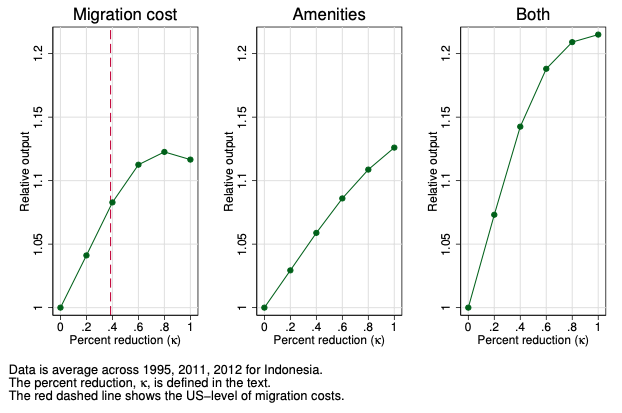

Figure 2 Output gain from reducing barriers to movement

We find important but not transformative, aggregate, impacts of these policies. The left-hand panel of Figure 2 shows the effects of percentage reductions in movement cost, the middle panel shows the effects of reducing amenity differentials, and the left-hand panel shows the effect of removing both amenity differences and migration costs. We find that output increases when migration costs are reduced, but the gains are modest. We predict an 8% output gain from reducing migration costs to the US level (indicated by the dashed red line in the figure), and a 12% gain from reducing migration costs to zero. The US is usually considered the archetype of a spatially mobile economy, so the 8% figure is probably the maximum attainable.

For the second experiment, we find that completely equalising amenities would lead to an increase in output of 12.6%. Finally, completely removing all migration costs and amenity dispersion together would lead to 21.5% output gain. The effect of reducing both barriers is slightly smaller than the sum of their independent effects, suggesting the policies are very mild substitutes.

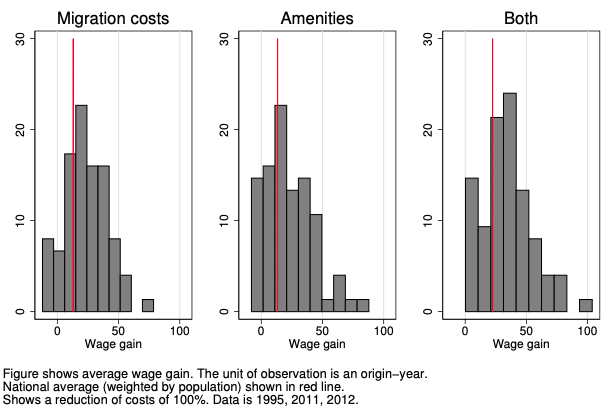

These averages, however, hide substantial heterogeneity across origin populations. While the average increase from eliminating all migration costs is 12%, the effect ranges from -12% to 79%. That is, the people born in some provinces may see a 79% increase in their average wage. We illustrate this heterogeneity in Figure 3. We also find substantial heterogeneity for the amenity counterfactual and the counterfactual of removing all frictions. The effects are strongly heterogeneous because some locations face much larger barriers to migration than others.

Figure 3 Distributional impacts, Indonesia

Limitations of our study

It is important to note some limitations of our efforts. First, we consider only static gains from migration, adding dynamic considerations may potentially increase the size of effects. Second, while our model is consistent with the aggregate data, a firmer microeconomic understanding of the mechanics of migrant selection would help to make more certain predictions. Finally, while we think it is useful to highlight the potential gains from suites of policy, real world impacts will only be had if definite and effective policies can be found.

Concluding remarks

Our results suggest that removing barriers to internal migration can lead to aggregate gains in productivity, albeit modest ones. Admittedly, the average gain we find hides substantial heterogeneity across origin populations. Policymakers must bear this mind if they target reducing barriers to internal migration as a means of improving productivity and thereby promoting economic growth. One important avenue of future research is deepening the mechanisms through which migration affects poverty.

References

Asher, S and P Novosad (2016), "Rural roads and local economic development", Darrmouth University.

Bryan, G, S Chowdhury and A Mobarak (2014), "Under-investment in a profitable technology : The case of seasonal migration in Bangladesh", Econometrica 82(5): 1671–1748.

Bryan, G and M Morten (2018), "The aggregate productivity effects of internal migration: Evidence from Indonesia", Journal of Political Economy (forthcoming).

Caselli, F (2005), "Accounting for cross-country income differences", in Handbook of Economic Growth 1: 679–741, Elsevier.

Gollin, D, D Lagakos and M Waugh (2014), "The agricultural productivity gap in developing countries", The Quarterly Journal of Economics 129(2): 939–993.

Harari, M (2017), "Cities in bad shape: Urban geometry in India", University of Pennsylvania.

Hsieh, C and E Moretti (2018), "Housing constraints and spatial misallocation", American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics (forthcoming).

Morten, M and J Oliveira (2018), "The effects of roads on trade and migration: Evidence from a planned capital city", Stanford Univeristy.