Cities can be engines of growth. How can policymakers realise the benefits of cities while minimising the drawbacks of urbanisation?

This episode of VoxDevTalks is the first in a mini-series of podcast episodes covering the BREAD-IGC virtual PhD-level course on urban economics.

In this episode of VoxDevTalks, Tim Phillips speaks to Edward Glaeser and Diego Puga who discuss why studying the dynamics of cities is essential for understanding economic development, the challenges cities face, and the areas that still require further attention.

The future of the developing world is urban

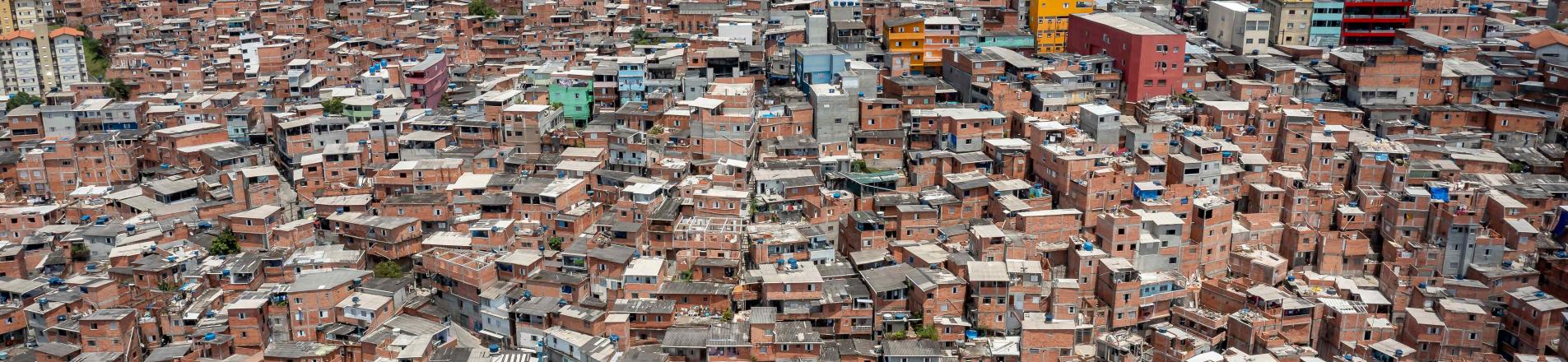

For much of the history of development economics, research has been focused on rural areas and subsistence agriculture. However, across the developing world, cities are growing rapidly.

‘Cities create promise, as well as enormous difficulties.’

This topic is critical for economists to study as it holds the potential to make the lives of urbanites better across the world. Additionally, most of the existing research on cities has not focused on low- and middle-income countries. Edward and Diego hope that BREAD-IGC's new lecture series can help boost a new wave of research.

The earnings gap between rural and urban areas

Universally people earn more in cities than in rural areas and the wedge between rural and urban areas is larger for LMICs. A similar gap between earnings exists between bigger and smaller cities, except there is not such a large difference between developed and developing countries.

'Those advantages of big cities tend to be greater for more skilled workers and that we can see very clearly in rich countries. In poorer countries, that's not so much the case. if anything the premium is smaller for more skilled workers.'

Glaeser reflects on his work in Brazil comparing the cities of the north and the cities of the south (Barza et al. 2024). In the south, cities support higher wages and wage growth, in contrast to cities in the north. He explains that the difference between the two can be explained predominantly by segregated workplaces; in the north low skilled workers are working with other low skilled workers in low skilled jobs.

The learning effect of cities

Cities can be engines of growth in part due to their potential to act as learning hubs, where individuals can improve their skills through face-to-face activity. Cities also enable people to interact with those with different skills and backgrounds. Segregation, whereby skilled and unskilled workers do not mix, can prevent these learning benefits from being realised.

A corollary to this is the challenge of making smaller cities attractive to skilled workers. Workers demand certain public goods, such as good schools and safer neighbourhoods, that are harder to find in smaller cities.

The gender gap in cities

With regards to learning, Glaeser comments on his work in Zambia on female entrepreneurship (Ashraf et al. 2019), which asks entrepreneurs where they are learning their skills from. Male entrepreneurs learn from other entrepreneurs whereas women learn from formal training, suggesting that they find it hard taking advantage of the benefits of urban interaction. This can be partly explained by their reported difficulty in dealing with male entrepreneurs.

Although cities remain a powerful force for female entrepreneurship there remains a significant gap by gender. Women entrepreneurs are often segregated into a few sectors such as food and apparel and choose to work in areas where they can partner with other women to not be expropriated by men.

It is not just female entrepreneurs who may be disadvantaged relative to men. Increasing security in cities and investing in public transport can have powerful effects for women, helping girls stay in school for longer and reach jobs that are further away. This is not just a problem faced by women in developing countries but also in rich countries. After having children, women are more likely to choose to work closer to home, thus giving up interesting opportunities more than men.

Are cities just different to begin with?

There are many alternative explanations for why we see greater growth in cities. Are the people in big cities just different? Do cities have intrinsic features about their location making them productive, thus incentivising people to move there, which then makes the city more productive?

There also may be static advantages from working in cities, learning advantages or competitive differentials that mean it is beneficial for a firm to locate in a city for reasons other than agglomeration economies.

To disentangle the positive relationship between size and productivity we require rich data that follows workers over time. Even without panel data, researchers have come up with inventive ways to analyse this relationship, such as by comparing workers who recently arrived to those who arrived earlier.

Overall, it seems reverse causality is not the issue and that cities drive greater productivity, rather than visa versa. Sorting may also be an important factor, but this may be a different form of sorting than first expected.

‘It may not be so much that workers that are very able for some kind of intrinsic characteristic go to big cities, but it is precisely the fact they go to big cities, that they spend time there and learn, that really raises their human capital and gives them skills and they end up doing better.’

Can cities be poverty traps?

In the US, those that grow up in high density urban neighbourhoods tend to have worse outcomes, even when holding family incomes constant. This relationship exists along other lines as well, including attending a school that is closer to the centre. Glaeser hypothesises that this story is one of segregation. Additionally, people living in poorer areas have more limited lives due to limited mobility through the city.

Research from Marx et al. (2013) shows that people living in slums for long periods of time in developing countries are not better off than those who just arrived. There are two potential explanations for this relationship, a poverty trap and the selection of who remains in the slum.

Infrastructure is lagging behind city growth

There is no single template to solve this problem. Different countries have addressed this challenge in many ways, including whether infrastructure is provided by the public or private sector, or some mix of the two. Different institutional models prevail in different regions.

Some things are ubiquitous between countries, however, such as the presence of minibuses throughout the developing world as a nimble and cheap way to navigate a city. Clean water is a fundamental challenge that needs to be addressed by a city council, including its maintenance and the necessary infrastructure.

Slow traffic speeds and long travel times are a prevailing feature of cities in LMICs. There seems to be a general intuition in advanced economies that simply fixing congestion will resolve this problem. Evidence suggests this is not in fact the case and that other factors are at play including road quality.

What is the last mile problem?

The last mile problem is, for example, when a benevolent investor creates a water main but that requires poor families to pay a considerable amount to connect to the main. Due to the high cost of doing so the poor family would rather stick with their worse technology. A key question for policymakers, in this scenario, is how families can be incentivised to connect to the mains.

Evidence from the US found that to get landlords to connect, they had to introduce a Pigouvian tax. Work by Glaeser and co-authors (Ashraf et al. 2016) examine what the right level of such taxation should be - any fine or tax needs to be sufficiently small not to incentivise extortion.

Building regulations in LMICs

Regulation in many developing countries is excessive, limiting urban expansion. For example, Mumbai’s land use regulation was particularly stringent, with a floor ratio of 1.25 that means houses could only be built to an average of one and a quarter stories. Regulation should support city growth as dense cities enable people to live close to their work and to each other.

‘Limiting height is making it difficult for developing world cities.’

Density is important but integration is also important. People of all skills and backgrounds convening together is what enables the productivity and skill benefits of cities to be realised. Placing too much emphasis on ensuring high-density and proximity could lead to segregation, as suggested by evidence on 15-minute cities (where essential services and amenities are within a 15-minute walk from any location).

What areas in urban economics require more research?

As cities become increasingly important in the development path of LMICs, the research remit grows, including on how incentives can impact how institutions provide water in cities, transportation research that uses new models and public health in cities given the past experience of the Covid-19 pandemic.

References

Ashraf, N, A Delfino, and E L Glaeser (2019), “Rule of law and female entrepreneurship,” Working Paper No. 26366, National Bureau of Economic Research. http://www.nber.org/papers/w26366.

Ashraf, N, E L Glaeser, and G A M Ponzetto (2016), “Infrastructure, incentives, and institutions,” American Economic Review, 106(5): 77–82.

Barza, R, E L Glaeser, C A Hidalgo, and M Viarengo (2024), “Cities as engines of opportunities: Evidence from Brazil,” Working Paper 32426. https://doi.org/10.3386/w32426.

Marx, B, T Stoker, and T Suri (2013), “The economics of slums in the developing world,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27(4): 187–210.