Giving government procurement officers more leeway in decision-making over expenses could save billions

Governments buy a lot of stuff. In 2015, for example, general government procurement spending in OECD countries represented an average of 29% of total general government expenditures or 12% of GDP (OECD 2016). The figure for developing countries is often at least as high; Pakistan, for example, spends around 20% of GDP on public procurement. As a result, weak and poorly designed procurement systems can substantially reduce the amount of money that governments have left to spend on other priorities. Ensuring value-for-money in all government purchases is a vital part of its mission to serve – and maintain the trust of – its citizens.

Optimum procurement policy: Strict rules or autonomy?

There are two main sides to the debate around optimum procurement policy. International organisations such as the OECD and World Bank tend to advocate for a policy of strict rules, combined with the development of strong monitoring and oversight institutions to ensure compliance. This may discourage egregious misuse of government funds, but it also means that procurement officers (POs) must deal with a lot of red tape and may be discouraged from innovating – or even punished for doing so – even when there is the potential for savings.

Procurement is also an important function in the private sector, however, where businesses tend to take the opposite approach; they generally grant considerable autonomy to POs, and trust them to use their discretion to seek out value for money. This philosophy is well summed up by Netflix’s five-word policy for expensing: “Act in Netflix’s best interest”. This approach calls for lighter monitoring during procurement and is often accompanied by pay-for-performance schemes that reward efficiency.

Researchers at the London School of Economics and Columbia have found an innovative way to adjudicate the merits of these two positions. They worked with the Government of Punjab in Pakistan to measure value-for-money around the purchase of generic goods,1 and to assess the impacts of giving POs either greater autonomy or financial incentives.

The price paid for generic goods varies considerably

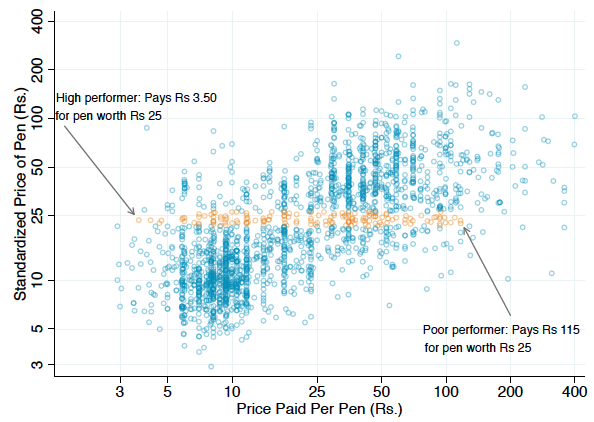

Data collected over the course of the study shows that there is considerable variation in the price paid by different public bodies for exactly the same good. Each point in Figure 1, for example, is a purchase of pens. The x-axis shows the price the public body actually paid for the pens and the y-axis shows what the item is actually worth. As the orange line indicates, POs paid anything between PKR 3.5 and 115 for pens that were worth PKR 25.

Figure 1 The standard cost of—and amount paid for—pens

While the cost of each individual item is small – PKR 115 is less than USD 1 – the volumes are large; the purchase of generic items such as these accounted for over half of non-salary expenditures in many of the offices that were a part of the study.

The savings from greater autonomy were considerable

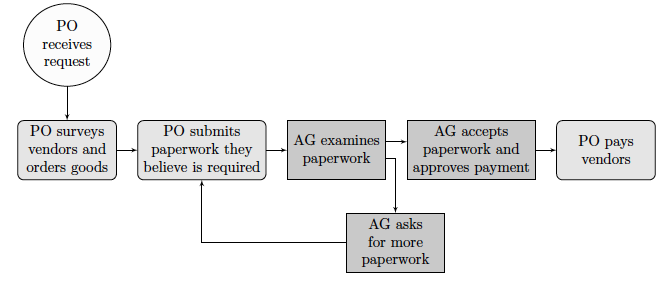

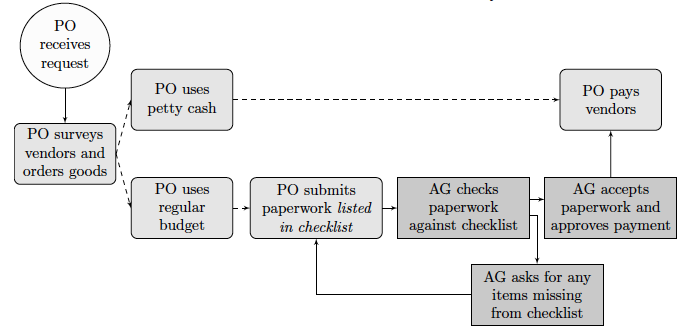

The study tried two different approaches to increasing procurement efficiency. The spending of each PO is monitored by an Accountant General (AG). The ‘autonomy’ treatment simplified or bypassed much of the pre-audit monitoring POs are subject to when procuring generic goods. As shown in Figure 2, a strict limit was placed on the types of documents AGs could ask for as part of the spending approval process, and POs were given full discretion over how they spent a portion of their budget.

Figure 2 Procurement process summary

Panel A Status quo procurement process

Panel B Procurement process under autonomy treatment

Intuitively, this increase in PO autonomy is likely to have two effects that work in different directions:

- Removing red tape and increasing autonomy to achieve value-for-money should decrease prices paid for goods;

- Lower oversight might increase wastefulness in either an active way (i.e. corruption) or a passive way (i.e. laziness).

The study found that providing procurement officers with additional autonomy led to a reduction in the average unit prices paid by 8–9%, indicating that the removal of waste caused by complying with the monitoring activities more than offsets the loss of benefits that monitoring provides. Even in the relatively small group of offices included in this experiment, this virtually costless intervention led to savings that were enough to fund the annual operation of an additional five schools or to add 75 hospital beds.

Incentives were less effective, though still offered value for money

The second ‘incentives’ treatment introduced performance pay for procurement officers, rewarding them financially for achieving greater value-for-money. The study found that the average impact of these incentives hovered just above zero. It seems that where monitoring is onerous, POs are too tangled up in red tape to do anything to improve their performance.

Despite the low per-unit savings, however, the rate of return on this treatment was substantial. The comparatively low cost of implementing the incentive scheme and the large volumes purchased meant that the government saved $1.45 for every $1 it gave out in bonuses.

Procurement in this context is highly demand-led and the items tracked in this study are highly generic, so neither treatment had any discernible effect on the variety, amount or composition of goods purchased, or the timing of procurement expenditure.

The effect of both treatments depended on the ‘type’ of monitor

The impact of these treatments varied considerably across participants. An important determinant of the success of the two treatments was the ‘type’ of AG assigned to monitor each PO. The autonomy treatment worked best – delivering around 15% in savings – when the AG was extractive (as measured by the extent to which they delayed approvals),2 while the incentives treatment worked best – delivering around 6% in savings – when the AG was effective. The fact that the autonomy treatment was more effective overall indicates that, in this context, the average AG is relatively extractive.

This is an important result; it implies that optimum allocation of authority between agents at different levels of a hierarchy will depend on their relative degrees of wastefulness. Other things being equal, the more wasteful the managers, the more savings that can be realised by shifting authority and providing frontline personnel more autonomy.

The appropriate response to inefficiency and corruption may sometimes be less monitoring, not more

More work is needed to understand whether this result holds in other contexts, and how these policies would affect the calibre of personnel attracted to procurement jobs in the long-term. For example, it may be that greater autonomy attracts dishonest POs, though it might also improve the quality of supervision; giving more autonomy to officers implies taking it away from the monitors, which may change the nature of AG applicants for the better.

Overall, this study indicates that we need to check our instinct to react to government inefficiency and corruption with increased monitoring; in many places, the elaborate system of pre-audit monitoring facing bureaucrats is probably doing more harm than good. Greater autonomy (and rigorous post-audit of purchases) may, counterintuitively, be a key part of the solution.

Editors’ note: This article was published in collaboration with VoxEU.

References

Bandiera, O, M C Best, A Q Khan and A Prat (2020), “The allocation of authority in organizations: A field experiment with bureaucrats”. Latest version available at: https://bit.ly/2UItDXP

OECD (2016), General government procurement as a percentage of GDP (2015). Data available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888933533131

Endnotes

1 Procurement officers were trained to enter detailed data on the attributes of the items they were purchasing into a web-based platform, and were audited to physically verify that the data was accurate.

2 Again, the authors are agnostic as to whether these delays are caused by active obstruction (i.e. corruption) or passive obstruction (i.e. laziness)