Highly competitive examinations for public service recruitment in India have detrimental economic effects

This article was posted in collaboration with Ideas for India.

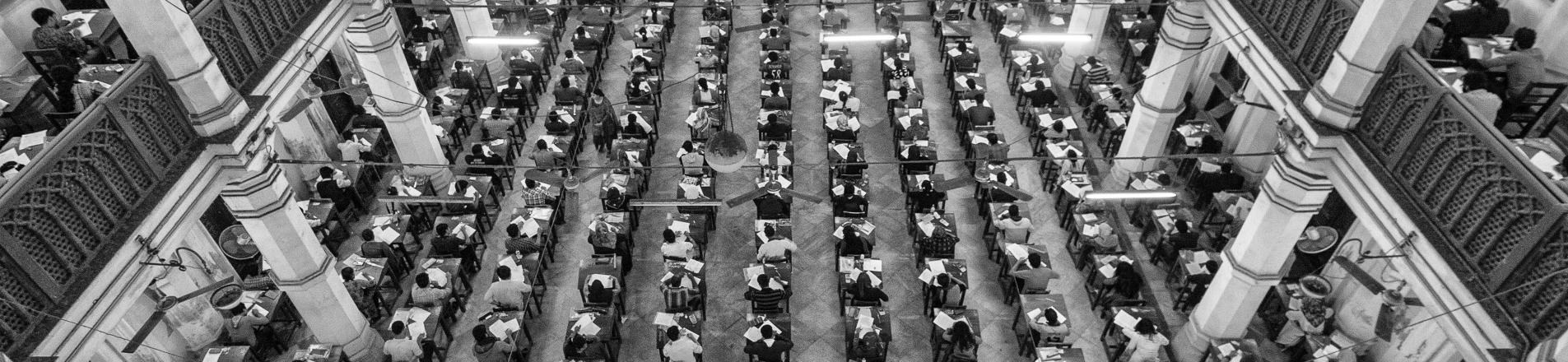

Each state in India has a Public Service Commission, which is a constitutional body that is independent of the government, and is responsible for filling state-level bureaucratic posts through a system of exams1. In Tamil Nadu, more than 300 candidates apply for each vacancy advertised through the state’s civil service exam system (that is, through the Tamil Nadu Public Service Commission, also known as TNPSC). Application rates are so high that, in 2013, more than one in four recent college graduates appeared for one of these exams. To remain competitive against so many applicants, over 100,000 individuals across the state stay unemployed and study full-time for these exams. To provide context, this is more than the number of people who participate in the state’s vocational training programmes every year.2

In a way, the fact that so many candidates participate in civil service exams is a victory for the reformers of public administration in the 19th and 20th centuries. For the longest time, the main problem with public sector recruitment was that it was not nearly competitive enough. Instead, government officials around the world would allocate bureaucratic jobs thorough patronage, which often had negative consequences for the productivity of the public sector workforce (Xu 2018, Colonnelli et al. 2020).

However, now that merit-based competition has reached extreme levels, the pressing question for public sector recruitment in India is whether these extreme levels of competition engender their own kind of negative side effects; and if so, how the unintended costs of the competition for government jobs can be successfully mitigated.

Does extreme competition impose long-term costs on candidates who participate in these exams but who are not ultimately selected? Theoretically, the answer is ambiguous. On the one hand, by studying for the exam candidates may build general human capital that improves their labour market outcomes even if they are not selected. On the other hand, the time spent out of employment and the disappointment of not getting selected may have long-term economic and social scarring effects. Identifying the net effect is an empirical question which remains to be answered.

Learning from the Tamil Nadu hiring freeze

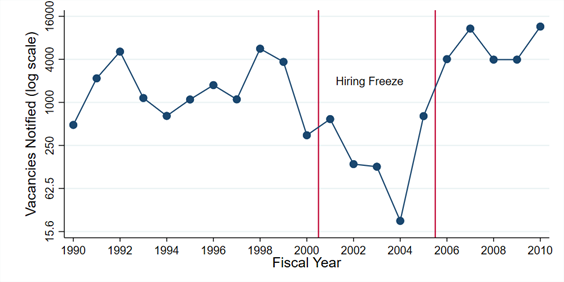

To address this question, in recent work (Mangal 2022) I study the socio-economic impacts of a policy that increased the competitiveness of public sector recruitment exams. Between 2001 and 2006, the government of Tamil Nadu implemented a partial hiring freeze, which reduced vacancy availability by 85% (see Figure 1), but otherwise left aggregate demand intact.

Figure 1: The hiring freeze

Notes: i) The figure plots measures of recruitment intensity for posts that were not exempted by the hiring freeze (that is, it includes all posts recruited through merit-based exams in the state government except police/firefighters, medical staff, and teachers). ii) The x-axis is the state government's fiscal year, which runs from April to March of the following calendar year. iii) The red lines mark the beginning and end of the hiring freeze. Fiscal year 2006 is not included in the hiring freeze since most of this fiscal year was not covered by the freeze, which ended in July 2006.

Candidates could have responded to the freeze by giving up on their dream of a government job and pursuing options in the private sector instead. However, during this time period, applications for the remaining vacancies increased by about 7%.

The most likely explanation for the increase in applications is that candidates spent more time on the ‘exam track’. My analysis focuses on male college graduates, a demographic group with both stable employment patterns across time and high labour force participation rates, which allows me to detect changes in their outcomes in response to the hiring freeze policy. Using data from the National Sample Survey, I find that the cohorts of male college graduates in Tamil Nadu who were most exposed to the policy were on average 9 percentage points less likely to be employed during the hiring freeze.

This is a sizeable effect, considering that the policy resulted in only 900 fewer jobs per exposed cohort across the entire state. For an economy as large as Tamil Nadu, this should be an otherwise imperceptible change in labour market tightness; and if the government were like any other employer, it is unlikely that we would have seen any effect. However, because government jobs receive such sustained and exclusive focus from candidates, changes in public sector recruitment policy can coordinate the behavior of a sizeable share of the labour market. As a result, we see swings in aggregate unemployment rates.

I measure how the same cohorts of college-educated men who spent more time out of employment during the hiring freeze fared in the labour market in the long-run. To do so, I use data from CMIE’s Consumer Pyramids Household Survey (CPHS), which tracks a panel of over 160,000 households. About 10 years after the hiring freeze ended, these cohorts appeared to be worse off on a wide range of indicators. They had lower employment rates; lower earning capacities; and delayed forming their own households. Moreover, the negative effects on candidates appeared to spill over to other household members: for example, elder members of the household appeared to delay retirement in order to compensate for the income shock.

The tendency towards excess competition

Why are candidates willing to invest so much in exam preparation? What can policy do to curb excessive competition? These are some of the questions I take up in a recently released report (Mangal 2023), which uses TNPSC’s internal administrative data to shed light on why candidates apply, why they persist, and what kinds of policies may affect candidate application behaviour.

Part of the problem is that tournaments, such as civil service exams, exhibit some of the classic features of a prisoner’s dilemma, a type of strategic interaction where what is individual rationality is at odds with social efficiency. For individual candidates, it may make sense to invest more in exam preparation (for example, by dedicating more time to exam preparation, and by paying for more sophisticated coaching classes) in order to beat the competition. However, when candidates study more, they force others to invest more so that they can keep up. These “rat race” effects can lead to an ever-increasing spiral of investment in exam preparation – even when that additional investment has zero to negative social value.

Implementing hard brakes on exam participation or investment is politically challenging. Many candidates see public sector employment as the only viable means of upward mobility. As a result, public sector recruitment is a highly charged subject. If candidates perceive that the government is shutting the door on this dream---such as by imposing a binding age limit---it is likely that the reaction will be explosive.

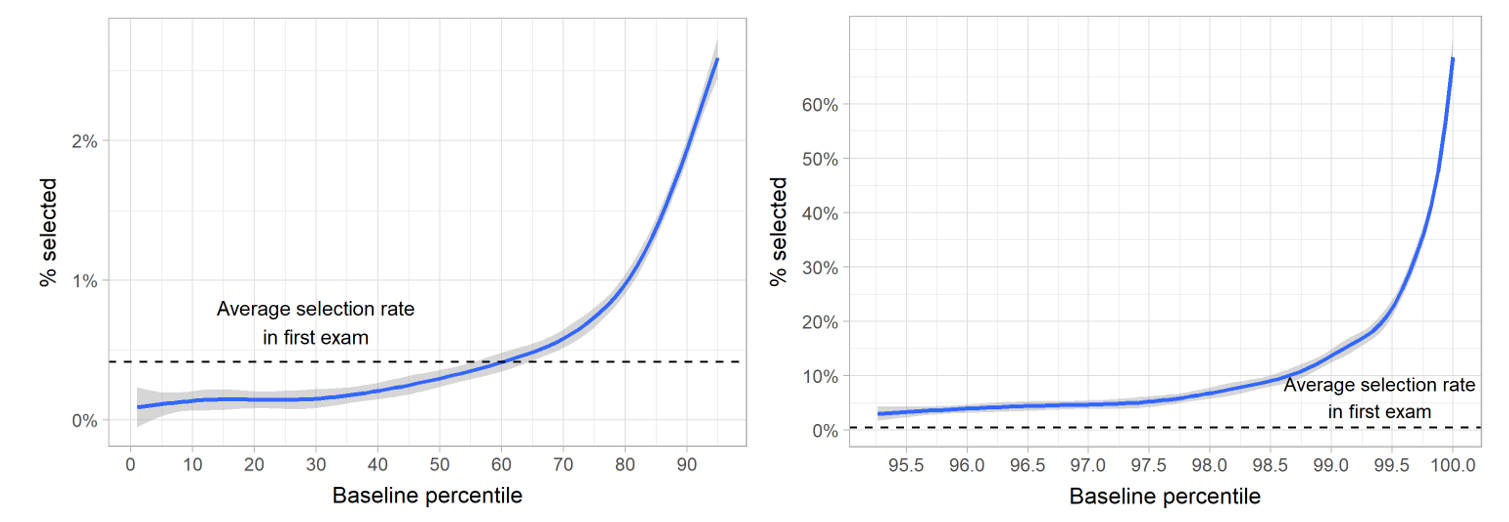

Other, more nuanced policies may accomplish the same goal in a more politically palatable way. For example, public service commissions may want to consider implementing conditional limits on the number of attempts. TNPSC’s internal data shows that the scores that candidates obtain on their first attempt is highly predictive of their ultimate chance of selection (see Figure 2). This tells us that candidates who have consistently failed to land in the top deciles of the distribution are unlikely to ever be selected. Governments can therefore make a reasonable case that a conditional limit policy would not take away opportunities from people who are making sufficient progress towards their goal.

Figure 2: Candidates’ initial score and probability of selection for the bottom 95% (left) and top 5% (right)

Notes: i) This figure uses a sample of candidates who: a) applied to any TNPSC exam for the first time in the 2016 “Group 4” exam; b) were not selected in that exam; and c) reapplied in some TNPSC exam (including non-Group 4 exams) after 2016. ii) The vertical axis measures the probability of selection in any subsequent TNPSC exam. iii) The grey band indicates the 95% confidence interval of the estimate. A 95% confidence interval is a measure of the uncertainty of the estimate: if one were to draw repeated samples from this population, 95% of the time the calculated confidence interval would contain the true effect.

Another way to reduce the costs of highly competitive exams is to increase the social value of exam preparation for candidates who are not successful. For example, there is potential for the recruitment process to double as a public skill certification exercise. After all, the government already goes through a great deal of difficulty to measure the ability of over 1.5 million candidates who appear for the exams each year. Why wouldn’t at least some firms in the private sector benefit from seeing the score information when they are trying to decide who to hire? If there are no firms that benefit from this information, the government should seriously reconsider its own rubric; but if the information is useful, there is an opportunity to use it to help the thousands of candidates who score very well, but are not selected, find employment.

A new way to tackle unemployment among educated youth

The problem of unemployment among educated youth is terribly stubborn. However, public sector recruitment policy provides a set of relatively unexplored mechanisms that we may able to use to make a dent in the problem. In my report, I lay out many more ideas for how public sector recruitment policy can be used to improve the functioning of the labour market. Even then, I believe we have only begun to explore the possibilities. There is scope for more research, debate, and discussion around how public sector recruitment policy can be enlisted to tackle some of the key challenges in the Indian labour market.

References

Colonnelli, E, M Prem and E Teso (2020), “Patronage and selection in public sector organizations”, American Economic Review, 110(10): 3071-3099.

Jeffrey, C (2010). "Timepass: Youth, class, and the politics of waiting in India", Stanford University Press.

Mangal, K (2022), "The Long-Run Costs of Highly Competitive Exams for Government Jobs", Unpublished manuscript.

Mangal, K (2023), "The Indian Labor Market Through the Lens of Public Sector Recruitment", Working Paper, Centre for Sustainable Employment, Azim Premji University.

Xu, Guo (2018), “The costs of Patronage: Evidence from the British Empire”, American Economic Review, 108(11): 3170-98.