Chile’s OECD-aligned tax reform did not shift transfer pricing behaviour or generate additional tax revenues.

It has long been shown that multinational corporations reduce their global tax payments by shifting profits to low-tax countries (e.g. Jenkins and Wright 1975, Grubert and Mutti 1991, Hines and Rice 1994). Such tax avoidance and evasion significantly affects the public revenues collected around the world (Clausing 2016, Blouin and Robinson 2020, Torslov et al. forthcoming). According to the OECD, tax revenue lost due to international profit shifting could range between USD 100–240 billion (OECD 2021).

In light of this, many countries have put in place standardised regulations that aim at curbing international profit shifting. However, little is known about the effectiveness of these policies, since their gradual introduction and limited access to the required data make rigorous evaluations difficult.

A natural experiment on transfer pricing

In a new paper (Bustos et al. 2022), we shed new light on the effectiveness of international regulations to limit profit shifting. Following Chile’s accession to the OECD, the country implemented a major tax reform in 2011, which introduced the OECD transfer pricing standards of the time. The reform introduced extensive reporting requirements for multinational firms to justify their international intra-firm transfers.

Through legal changes and increased resources, the tax authority was equipped with the tools necessary to enforce the new transfer pricing rules. While Chile had previously lagged behind other countries in the adoption of such policies, the country was viewed as a leader in the regulation of international profit shifting shortly after the reform (Mescall and Klassen 2018).

This unique natural experiment, together with access to micro-level administrative tax and customs data, enable us to provide an extensive evaluation of the OECD regulations on profit shifting at the time. We combine our quantitative analysis with in-depth interviews carried out with Chilean transfer pricing experts, accountants at multinational firms, and officers at the tax authority. We also iterate back-and-forth between the quantitative and qualitative analysis testing insights from the interviews in the data and vice versa.

Assessing success of the reform: Understanding multinationals’ payment patterns at baseline

To understand if the reform was effective, we first need to take a step back and ask if subsidiaries of multinationals in Chile are engaging in international profit shifting to begin with. We can address this question by comparing the payments a multinational makes to its foreign affiliates to the payments the same multinational makes to unrelated firms in the same destination country.

Specifically, we assess how transactions with affiliates abroad vs. transactions with other firms in the same destination country respond to changes in the tax rate of that country. Indeed, we find that multinationals active in Chile seem to make tax-motivated payments to their foreign affiliates (i.e. intra-group payments) that are suggestive of profit shifting. A one percentage point reduction in the tax rate of the destination country is associated with a 5.5% increase in payments to affiliates in that country.

We can then use a difference-in-differences event study design to investigate how these tax-motivated payments evolve over time. This provides a direct insight into the effectiveness of the 2011 reform in reducing the profit shifting behaviour of multinationals active in Chile at the time.

The reform had no observable impact on transfer payments by multinationals

Contrary to the government’s expectations, we find that the reform had no effect on any of the key profit shifting channels by multinationals.

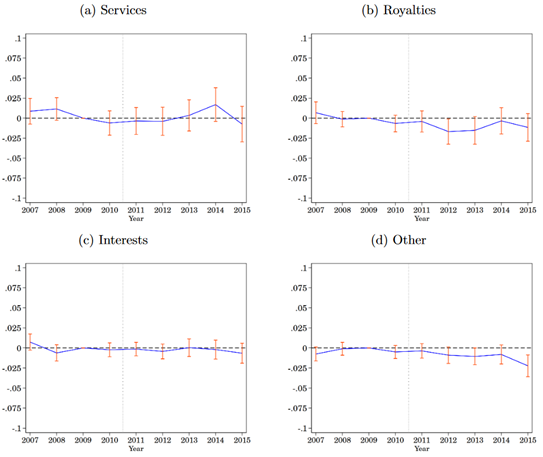

- There is no reduction in the responsiveness of intra-group payments to destination country tax rates (Figure 1). (If this were the case, the point estimates would be positive in the post-treatment period.)

- We also find no effects on unit-prices in intra-group trade of goods.

- Since we see no impact on any of these margins of transfer pricing, it is not surprising that there is also no effect on overall tax payments by multinational firms in Chile.

Figure 1: Impact of the reform on the sensitivity of international payments to changes in the destination country tax rate

Notes: The figure shows the sensitivity of international payments to changes in the destination country tax rates, for payments to affiliates compared to payments to non-affiliates in the same destination country. Standard errors clustered at the firm level. Vertical bars represent 90% confidence intervals. Year 2009 is normalised to zero.

How can one reconcile the ineffectiveness of the reform with the widely held view that the reform was a sea-change in the taxation of multinationals in Chile? One key answer lies in the dynamic which unfolded in the tax consulting industry.

The role of the tax advisory industry

The combination of quantitative analyses and qualitative analysis reveals one great beneficiary of the reform: the tax consulting industry.

- Seeking compliance support with the new regulation, multinationals newly availed themselves of international transfer pricing experts from the ‘Big 4’ consulting firms (i.e. Deloitte, EY, KPMG and PWC).

- Given the internationally standardised nature of transfer pricing regulations, these consulting firms were able to adapt quickly to the demand shock, by flying in experts from countries like Argentina, Colombia, Spain or Venezuela.

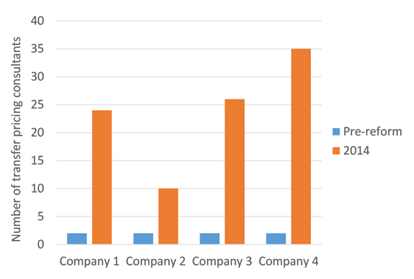

- Our consultations reveal that the number of transfer pricing consultants at the ‘Big 4’ consulting firms in Chile increased 12-fold in response to the reform (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Number of transfer pricing consultants in ‘Big 4’ consulting firms in Chile

Notes: Data obtained from interviews with representatives from the Big 4 consulting firms in Chile.

While the multinationals usually approached the consulting firms for compliance support, consultants then leveraged these relationships by up-selling these clients. This led many multinationals to engage in more complex tax planning after the reform. Through such tax planning, consultants helped multinational firms “optimise” their tax payments.

The quick response of the tax consulting industry in Chile highlights a broader issue beyond the Chilean case. Namely, tax authorities fall short of the resources (in the tax consulting industry) which corporations can deploy to reduce their global tax bill. A report from the British Parliament (Public Accounts Committee, 2013) puts it as follows:

HMRC [the British tax authority] appears to be fighting a battle it cannot win in tackling tax avoidance. Companies can devote considerable resource to ensure that they minimise their tax liability. There is a large market for advising companies on how to take advantage of international tax law, and on the tax implications of different global structures. The four firms employ nearly 9,000 people and earn £2 billion from their tax work in the UK. In the area of transfer pricing alone, there are four times as many staff working for the four firms than for HMRC.

This quote reveals the imbalances in the resources available for tax enforcement vs. those utilized for tax planning in the private sector. If even the fiscal authority of a large, high-income country like the United Kingdom is so outnumbered by transfer pricing professionals on the firm side, then it is easy to imagine that the problem is even more challenging for low- and middle-income countries with fewer resources.

Qualitative insights in the data: Consolidation of cost centres emerges as a key recommendation

One key aspect of tax planning advice uncovered in the interviews is the consolidation of cost centres to fewer countries. This finding illustrates our ability to iterate between qualitative and quantitative analysis, testing hypotheses generated from the interviews in the administrative data.

In fact, multinationals appear to have followed this advice. After the reform in 2011, multinationals concentrated their payments to affiliates abroad in fewer countries (Figure 3). This reduction happens only for non-tax haven countries and—in line with the mechanisms described in the interviews—is concentrated in payments for services. These intra-group service payments usually comprise payments on marketing, HR, or sales — for which it is particularly challenging for a tax authority to ascertain whether they are priced in accordance with transfer pricing standards.

Figure 3: Effects of the reform on the consolidation of cost centres (Affiliate vs. Non-affiliate Payments)

Notes: The figure shows the impact estimates on the number of countries to which multinational firms make payments, obtained in a difference-in-differences event study design comparing affiliate to non-affiliate payments. Estimation includes multinational firms only. 2009 is normalised to zero; 2010 serves as a placebo year. Standard errors clustered at the firm level. Outcomes winsorised at the 99th percentile of non-zero values. Vertical bars represent 90% confidence intervals.

Implications for policy: Reforms benefiting tax planning rather than tax collection

Overall, these results suggest that accounting for the tax advisory sector is key to understanding the effects of tax regimes. New reporting and compliance requirements can create an incentive to purchase external tax preparation services, which may in turn facilitate the adoption of more sophisticated tax planning strategies.

Given that the Chilean reform increased both compliance and enforcement costs, but did not result in additional public revenue collections, our combined evidence suggests that the reform benefited the tax advisory industry while decreasing overall welfare. In the race between enforcement and tax planning, in this case, tax planning seems to have won.

Editor's Note: This article was previously published under the title "Fighting a losing battle: How the tax planning industry undermines tax enforcement efforts"

References

Blouin, J and L Robinson (2020), "Double counting accounting: How much profit of multinational enterprises is really in tax havens?", Available at SSRN 3491451.

Bustos, S, D Pomeranz, J C S Serrato, J Vila-Belda, and G Zucman (2022), "The race between tax enforcement and tax planning: Evidence from a natural experiment in Chile", National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper No. 30114.

Clausing, K (2016), “The effect of profit shifting on the corporate tax base in the United States and beyond”, National Tax Journal 69(4): 905-934.

Grubert, H and J Mutti (1991), “Taxes, tariffs, and transfer pricing in multinational corporate decision making”, The Review of Economics and Statistics 285-293.

Hines Jr., J and E Rice (1994), “Fiscal paradise: Foreign tax havens and American business”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 109(1): 149-182.

Jenkins, G and B Wright (1975), “Taxation of income of multinational corporations: The case of the United States petroleum industry”, The Review of Economics and Statistics 1-11.

Mescall, D and K Klassen (2018), “How does transfer pricing risk affect premiums in cross‐border mergers and acquisitions?”, Contemporary Accounting Research 35(2): 830-865.

OECD (2021), Addressing the tax challenges arising from the digitalisation of the economy.

Tørsløv, T, L Wier, and G Zucman (forthcoming), “The missing profits of nations”, Review of Economic Studies.