Households are willing to pay for public health insurance, but those who pay to enrol have higher average costs than those who enrol when insurance is free. How then should governments set premiums for health insurance given the high costs of raising revenue?

A basic tenet of economics is that, because people are risk averse, reducing risk (from health, weather, unemployment, etc.) can generate significant value. This is particularly true in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where income can be highly variable. Health is a particularly salient source of risk, and one which has large consequences for both well-being and income (e.g. Gertler and Gruber 2002). In response, many LMICs – including China, India, Mexico, Thailand and others – have moved in recent years to provide free health insurance to the poorest individuals and households.

However, public subsidies for insurance come at a cost, either in future taxes or in cuts to other needed government programmes. As governments consider expanding eligibility for public insurance beyond the poorest households to those in the middle of the income distribution, it is important to consider how public insurance should be priced. Should it be fully subsidised (i.e. free), partly subsidised, or completely unsubsidised?

The case for charging for health insurance

Middle-income households may have a higher willingness to pay (WTP) for insurance than the very poor. In addition, providing insurance (or other services) for free to middle-income households may create significant economic distortions in LMICs if raising revenue has a high cost — either because there are many other compelling uses of government funds, or because raising taxes distorts economic activity, or both. Asking households to bear some or all of the cost of insurance can reduce the pressure that safety net expansions put on public finances.

The case for subsidising health insurance in India

While there may be a case for charging households for insurance, there is also a case for using government resources to make it partly or fully subsidised. In our setting (rural and peri-urban Karnataka, India), even households who are above the poverty line have incomes that are quite low (the poverty line in Karnataka at the time of the study was a monthly household income of 900-1100INR or US$52-64 at PPP) and accessing loans or drawing on savings may be difficult. So, asking households to pay positive premiums for insurance coverage could mean that many, even those who value it, may be unable to pay, due to insufficient cash in hand and other pressing needs (see Casaburi and Willis 2018 and the accompanying VoxDev article).

Moreover, charging for insurance raises the prospect of “adverse selection.” When households know more about their likely health costs than the insurer does, it makes it infeasible for the insurer to charge households prices which fully reflect their individual risk. In theory, at a certain price of insurance, only households whose expected health costs are higher than the price will buy insurance. If adverse selection is present, charging higher prices raises average costs for the insurer as only those with higher expected health costs will buy insurance, which in turn reduces the financial gain to the government of charging premiums (e.g. Einav and Finkelstein 2011).

Who buys health insurance at different prices in India?

To inform optimal prices for insurance, policymakers need answers to two questions. What share of people choose to enrol in insurance at different prices, i.e. what is the demand curve for insurance? Do those who buy insurance at higher prices have higher costs than those who do not, i.e. how severe is adverse selection?

We conducted a large-scale randomised controlled trial (RCT) in Karnataka, India, to answer these questions. We offered an at-scale government insurance product, RSBY - the National Health Insurance Programme - to above poverty-line households, a category of people not eligible for RSBY outside the study. RSBY covered inpatient care and some outpatient surgeries at participating hospitals, subject to an annual cap of INR 30,000 per household. This cap would cover roughly 10 times the price of an MRI, twice the price of an appendectomy, or 4 times that of a c-section delivery.

To understand the causal effect of price on demand, we randomised the price households faced, which allows us to overcome the concern that, in a non-randomised setting, the price households pay may be correlated with other characteristics such as initial health, wealth and location. Households were randomly assigned to a price of 0 (“free insurance”), a price of roughly INR 200 (“paid insurance”), or a price of roughly INR 200 plus an equal-value unconditional cash transfer (“paid insurance plus transfer”). The third group allows us to understand whether consumers might be willing to pay for insurance even if unable to pay due to limited liquidity. Our study design also allows us to test for the effects of insurance on health, out of pocket spending and other outcomes, which we discuss in our working paper (Malani et al. 2024) and a companion VoxDev article.

Do consumers in India take up health insurance?

We find substantial demand (60% uptake) even when consumers were charged a price equal to the premium the government paid for insurance. (Under RSBY’s normal procedure, the government paid private insurance companies to provide a fixed amount of coverage to beneficiaries. In our study, households charged a premium had to pay this premium to enrol in RSBY). As expected, free insurance attracts higher demand: when consumers can enrol in insurance for free, approximately 79% of households take it up.

To test for adverse selection, we estimate the cost of the care that a given household would consume through RSBY. We find evidence of adverse selection: households who pay to enrol have higher average costs than those who enrol when insurance is free. Enrolled households who were charged the government’s cost to insure them had nearly three times greater utilisation rates vs enrolled households offered free insurance.

Finding the optimal price for health insurance

How, then, should the government set the price of insurance for above poverty line households—namely, the premium it charges a household in order to enrol in RSBY? Intuitively, the government should set the price at the point that the marginal benefit of spending one additional rupee on insurance equals the marginal cost of that additional rupee. The benefit of spending one more rupee comes from the fact that individuals value insurance, and consumer surplus increases when the government subsidises it. The cost of spending one more rupee has three parts. The first is mechanical: the government must pay the subsidy for each household who enrols, so higher subsidies directly raise costs. The second part captures how the per-enrolled-household cost changes when the price increases. If there is adverse selection, subsidising insurance will bring in lower cost individuals, so that the fiscal burden of subsidies goes up more slowly as the subsidy rises. Third, there is the government’s cost of financing, which can capture either the opportunity cost (if insurance subsidies crowd out other forms of beneficial spending) or the economic distortions involved in raising tax revenue (see e.g. Okunogbe and Tourek (2024) and the accompanying VoxDev podcast on the challenges LMICs face in collecting tax revenue).

Our experiment allows us to estimate the benefit from insurance – revealed by the demand curve – as well as how the government’s cost of offering insurance varies with price. For the government’s cost of financing, we follow other studies for LMICs and assume a marginal cost of public funds of 1.25 (e.g. the marginal cost of funds estimates from Ahmad and Stern (1987), Auriol and Warlters (2012) and Basri et al. (2021) lie between 1 and 2). This implies that raising one rupee of revenue costs a loss of 2.25 rupees, one rupee from the transfer and an extra 1.25 rupees from economic distortions, for example.

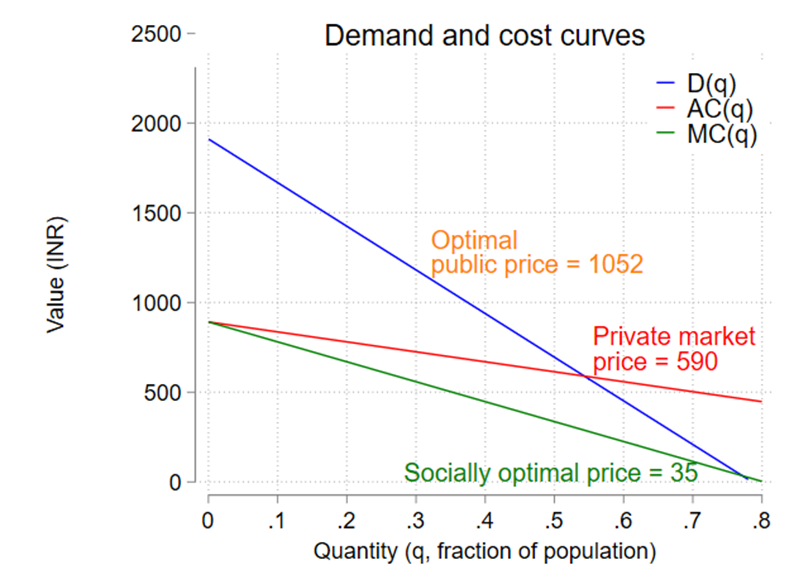

Our conclusions are shown in the figure below. In the (infeasible) social optimum, where there is no adverse selection and price could be set equal to marginal cost (i.e. the demand curve intersects the marginal cost curve), the socially optimal price would be just INR 35. In a private market, where adverse selection is present but there is no distortion from raising revenue, the optimal price would be set where demand equals average cost, at INR. 590. However, a public funder (i.e. a government), which faces both adverse selection and distortions from raising revenue would optimally charge a price of INR 1052.

Figure 1

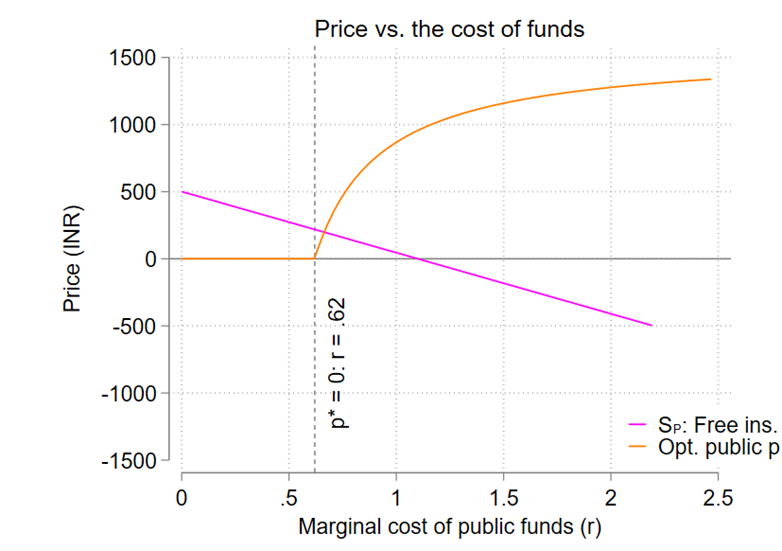

Given that there is considerable uncertainty in our estimate of the government’s cost of financing, we repeat our calculation of the optimal public price for a range of values. As can be seen in the orange line below, the optimal price is above zero when the government’s cost of financing is above 0.62 (meaning that raising a rupee of revenue creates a distortion of over 0.62 rupees). The figure also calculates whether offering free insurance is a net positive use of public funds. The value of free insurance is positive when the cost of financing is below roughly 1.1.

Figure 2

Takeaways for health insurance prices in India

Many households in our sample were willing to pay for public health insurance, underscoring that insurance can be valuable along many dimensions. Although, as we discuss in our paper, we do not find evidence that insurance improves health, insurance may contribute to peace of mind and/or protect households from catastrophic health costs. Nonetheless, in a context such as India, where it is costly for the government to raise revenue, providing health insurance for free to above-poverty line households does not appear to be an optimal use of government funds. Improvements in the ability of LMICs to collect tax revenue without distorting economic activity may strengthen the case for free public health insurance for middle-income households.

References

Ahmad, E., and Stern, N. (1987), “Alternative Sources of Government Revenue: Illustrations from India,” The Theory of Taxation for Developing Countries.

Auriol, E., and Warlters, M. (2012), "The Marginal Cost of Public Funds and Tax Reform in Africa," Journal of Development Economics, 97(1): 58-72.

Basri, M. C., Felix, M., Hanna, R., and Olken, B. A. (2021), "Tax Administration versus Tax Rates: Evidence from Corporate Taxation in Indonesia," American Economic Review, 111(12): 3827-3871.

Casaburi, L., and Willis, J. (2018), "Time versus State in Insurance: Experimental Evidence from Contract Farming in Kenya," American Economic Review, 108(12): 3778-3813.

Einav, L., and Finkelstein, A. (2011), "Selection in Insurance Markets: Theory and Empirics in Pictures," Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25(1): 115-138.

Gertler, P., and Gruber, J. (2002), "Insuring Consumption Against Illness," American Economic Review, 92(1): 51-70.

Malani, A., Kinnan, C., Conti, G., Imai, K., Miller, M., Swaminathan, S., Voena, A., and Woda, B. (2024), Evaluating and Pricing Health Insurance in Lower-Income Countries: A Field Experiment in India. National Bureau of Economic Research, No. w32239.

Okunogbe, O., and Tourek, G. (2024), "How Can Lower-Income Countries Collect More Taxes? The Role of Technology, Tax Agents, and Politics," Journal of Economic Perspectives, 38(1): 81-106.