Production delays, sudden windfalls, and political reactions after discoveries create major challenges for local governments in Brazil

Over 300 giant oil or gas discoveries (greater than 500 million barrels) have been made across 39 countries since 2000, with the largest number occurring in Brazil. Resource discoveries often provoke euphoria and grand development promises by leaders – but these promises prove difficult to fulfill. While discoveries attract foreign direct investment (Toews and Vézina 2022), they can also intensify rent-seeking and corruption (Vicente 2010), increase weapons imports (Vézina 2021), and trigger armed conflict (Lei and Michaels 2014). Furthermore, the road from discovery to commercial production is highly uncertain: discoveries often suffer long delays or never produce at all (Mihalyi and Scurfield 2020, Mihalyi 2020).

Governments affected by natural resource discoveries must manage political reactions in their aftermath, adjust to frequent production delays and disappointment, and spend resource windfalls effectively – if and when they arrive. In recent research (Katovich 2024), I study the subnational impacts of offshore oil and gas discoveries in Brazil, focusing on local public finances, public goods provision, development outcomes, and politics. I find that post-discovery production realisations are highly heterogeneous, and that affected local governments struggle to convert windfall revenues into meaningful development gains.

Offshore oil discoveries and revenue sharing rules create a natural experiment

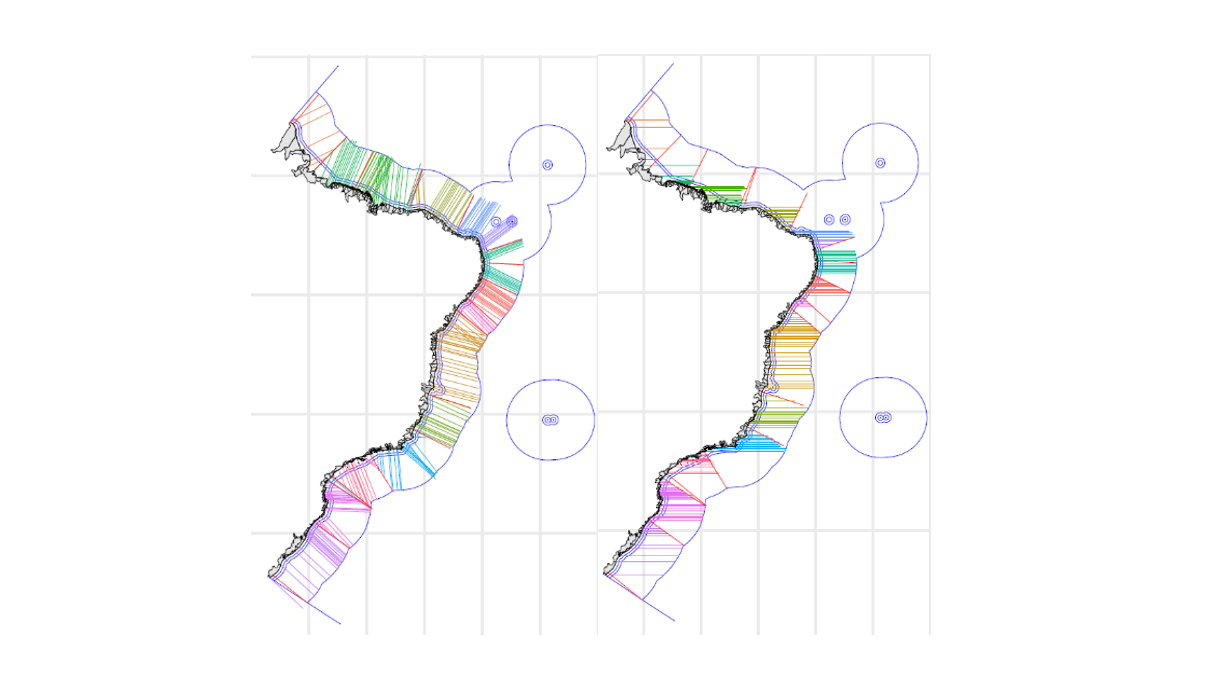

Brazil experienced a wave of major offshore oil and gas discoveries between 2000 and 2017. Discoveries have virtually no connection to neighboring coastal municipalities since they are made by multinational corporations operating hundreds of kilometers offshore and servicing installations from distant ports. Nevertheless, formulaic revenue sharing rules guarantee that a significant share of revenues from oil and gas production goes to geographically aligned municipalities. I reconstruct catchment zones formed by projections of coastal municipal boundaries in Figure 1.

This setup allows local governments to predict whether they will benefit from an offshore discovery, and creates a quasi-experimental context for me to estimate the causal effects of discovery announcements and subsequent revenue realisations on local governance. To ensure comparability between discovery-treated municipalities and controls, I restrict my sample to the subset of coastal municipalities that experienced exploratory oil and gas drilling between 2000-2017. Conditional on the presence of exploratory drilling, the occurrence of discoveries is as-if-random (Cavalcanti et al. 2019).

Figure 1: Projections of municipal boundaries determine offshore catchment zones

In Brazil, discoveries led to feast or famine for local governments

Forty-eight Brazilian municipalities experienced major offshore oil and gas discoveries between 2000-2017. Of these, less than half received 50% or more of the revenues they could have expected based on standard offshore production assumptions, announced discovery volumes, and Brazil’s revenue sharing rules. Figure 2 plots post-discovery oil revenue forecasts versus realised revenues for select municipalities, illustrating how some communities were “satisfied” by post-discovery realisations, while others were left “disappointed.” These variations in post-discovery revenue realisation are also exogenous to municipalities – driven by undersea geology, global price fluctuations, and oil companies’ internal decision-making.

Figure 2: Examples of municipal revenue forecasts (red) vs realised revenues (black)

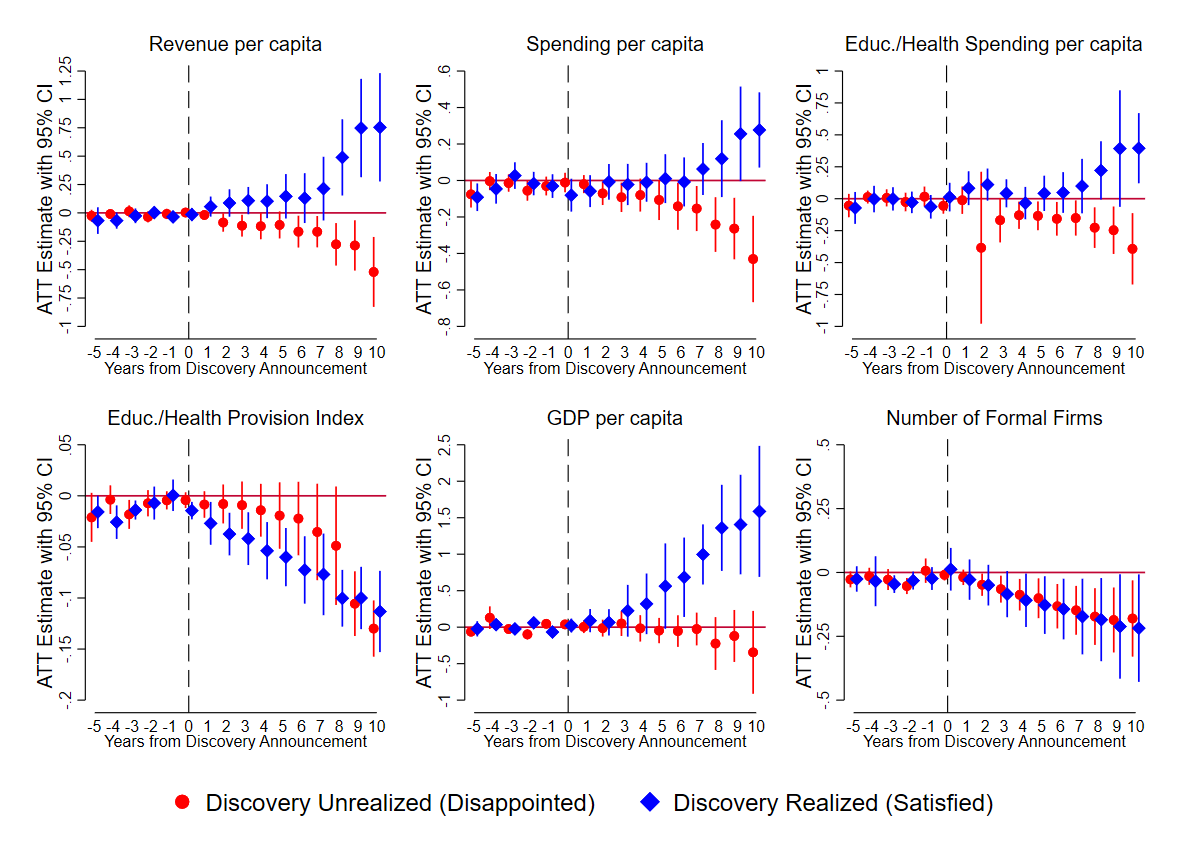

Municipal public finances do not react immediately to discovery announcements, likely due to constraints imposed by a fiscal responsibility law that limits deficit spending. As production ramps up 5-10 years after a discovery announcement, municipalities’ type emerges (i.e. ‘‘disappointed’’ or ‘‘satisfied’’) and outcomes for the two groups diverge sharply (Figure 3). In places where discoveries produce, per capita revenues increase by 88% after ten years relative to control municipalities. Per capita oil revenues increase by a striking 6,800% (growing from 1% to 42% of baseline average annual income). Per capita spending increases by 20%; spending on health and education increases by 27%.

Despite growth in spending, real public goods provision in “satisfied” places worsens relative to controls following a discovery announcement. Further highlighting the disconnect between resource windfalls and real development outcomes, municipal GDP per capita (which includes oil revenues mechanically) increases by 289% ten years on from a discovery, yet formal employment and firm registrations stagnate or decline. These disconnects may be the result of limited capacity to spend sudden, large windfalls effectively.

In contrast, “disappointed” municipalities that experience dud discoveries see revenues decline by 27% after 10 years – largely due to falling tax revenues (-37%) and federal/state transfers (-9%). Consequently, per capita spending declines by 24%, per capita investment by 57%, and education and health spending by 26%. Public goods provision worsens significantly relative to never-treated controls.

Figure 3: Public finance, public goods provision, and economic outcomes after discoveries

Political reactions to oil discoveries

Since local politicians control how oil revenues are spent, discovery announcements increase the perceived value of holding office. Following a discovery, I measure significant increases in the number of candidates running for municipal council and the number and value of campaign donations to local candidates. Besides increasing political competition, discoveries attract less-educated candidates: average schooling levels of elected politicians fall by 18% after a discovery announcement, which is indicative of rent-seeking (Melo and Tigre 2022).

I also find that voters punish incumbent politicians for disappointing discovery realisations: mayors are 12% less likely to win reelection when a municipality’s discovery payoff is less than expected at the time of an election. Politicians may over-promise after discovery announcements, and voters may interpret subsequent shortfalls as evidence of corruption or incompetence. Increased political turnover in disappointed places could disrupt public service delivery and governing capacity (Akhtari et al. 2022, Toral 2023).

Policy implications

Countries including China, Côte d'Ivoire, Egypt, Guyana, Mozambique, Namibia, Turkey, and Vietnam have recently made giant oil and gas discoveries, and seek to convert this natural capital into economic development. Yet many contend with symptoms of the resource curse – including exposure to discovery uncertainty and political disruptions after discovery announcements.

At the subnational level, revenue allocation rules that concentrate resource revenues in specific places make local governance more difficult and exacerbate regional inequalities. Spreading risk over a wider exploration portfolio would smooth idiosyncratic outcomes in individual fields, dilute disappointment, and avoid overwhelming local administrative capacity in places that ultimately receive windfalls. National leaders should manage discovery expectations and actively communicate with local leaders in affected areas to support capacity-building in preparation for windfalls and appropriate place-based policies in case of delay or disappointment. In Brazil, enterprising local governments have introduced innovative policies to manage uncertain oil revenues, including sovereign wealth funds and a universal basic income programme (Waltenberg and Katz 2023).

Conclusion

The literature on discovery impacts has traditionally treated discoveries as homogeneous events. In reality, the scale and timing of post-discovery production is highly uncertain, leading to radically different experiences – and policy prescriptions – in satisfied versus disappointed places. As resource exploration moves into deeper waters and more remote locations, production delays are likely to grow, and efforts to contain climate change increase the likelihood that discoveries will become stranded assets (Welsby et al. 2021). These trends highlight the importance of understanding governance and development dynamics in the context of resource uncertainty, shortfalls, and shocks.

References

Akhtari, M, D Moreira and L Trucco (2022), "Political turnover, bureaucratic turnover, and the quality of public services." American Economic Review, 112(2): 442–493.

Cavalcanti, T, D Da Mata and F Toscani (2019), "Winning the oil lottery: the impact of natural resource extraction on growth." Journal of Economic Growth, 1:79–115.

Katovich, E (2024), "Winning and losing the resource lottery: governance after uncertain oil

discoveries." Journal of Development Economics, 166(103204).

Lei, Y and G Michaels (2014) "Do giant oilfield discoveries fuel internal armed conflicts?" Journal of Development Economics, 110:139-157.

Melo, C and R Tigre (2022), "Are educated candidates less corrupt bureaucrats? evidence from randomized audits in Brazil." Economic Development and Cultural Change, forthcoming.

Mihalyi, D (2020), "The long road to first oil." Working Paper.

Mihalyi, D and T Scurfield (2020), "How Africa’s prospective petroleum producers fell victim to the presource curse." Extractive Industries and Society, 8(1):220-232.

Toews, G and P L Vézina (2020), "Resource discoveries, FDI bonanzas, and local multipliers: evidence from Mozambique." The Review of Economics and Statistics, 104(5):1046–1058.

Toral, G (2023), "Turnover: how lame-duck governments disrupt the bureaucracy and service delivery before leaving office." Working Paper.

Vézina, P L (2021), "The oil nouveau-riche and arms imports." Journal of African Economies, 349–369

Vicente, P C (2010), "Does oil corrupt? Evidence from a natural experiment in West Africa." Journal of Development Economics, 92(1):28–38.

Waltenburg, F and P Katz (2023), "Renda básica e economia solidária: o exemplo de Maricá." Cortez Editora.

Welsby, D, J Price, S Pye and P Ekins (2021), "Unextractable fossil fuels in a 1.5 °C world." Nature, 597(7875):230–234.