Electronic tax filing lowers compliance costs for firms while reducing the gap in tax revenues between those firms more likely vs less likely to evade

Editor's Note: For more on ways to increase tax compliance read the VoxDevLit on Taxation and Development.

E-government is a growing phenomenon

Technology is transforming the way governments function and interact with citizens. From electronic public financial management systems to digital delivery of social programmes and many other functions, these e-government initiatives typically seek to improve service delivery and efficiency. Often, they also aim to combat corruption by automating systems and reducing officials’ discretion (Lewis-Faupel et al. 2016, Muralidharan et al. 2016, Banerjee et al. 2020).

Tax administration is an important application of e-government in developing countries. Traditional tax systems in these countries are often characterised by high compliance costs for taxpayers, inefficient data processing, and frequent interactions between tax officials and taxpayers that present opportunities for collusion and/or extortion. This may contribute to their low fiscal capacity (Gordon and Li 2009, Besley and Persson 2014). As of 2015, 126 countries had adopted electronic filing (henceforth, e-filing) of taxes to replace in-person submission to tax officials as a way of addressing these problems, and this number continues to grow.

E-filing has ambiguous theoretical effects

However, e-filing may not deliver its expected benefits or may even lead to worse outcomes for some taxpayers. For example, when third-party reporting or other means of verifying income are limited, tax officials may use information gathered through frequent interactions with taxpayers to verify filing submissions. Since e-filing removes this ex-ante check, it could lower tax revenues. Given the rising prevalence of e-filing and its ambiguous potential effects, it is important to understand its impact.

Measuring the impact of e-filing

In a recent paper (Okunogbe and Pouliquen 2022), we examine the impact of e-filing adoption on compliance costs, tax payments, and bribe payments using data from small and medium-sized businesses in Dushanbe, the capital city of Tajikistan.

Tajikistan introduced e-filing for firms in 2012 to address tax administration challenges such as high compliance costs and corruption. However, due to a lack of awareness, and initial high registration costs, less than 30% of small- and medium-sized firms were registered in 2014. We worked with the tax administration to design a programme to increase e-filing adoption and measure its impact.

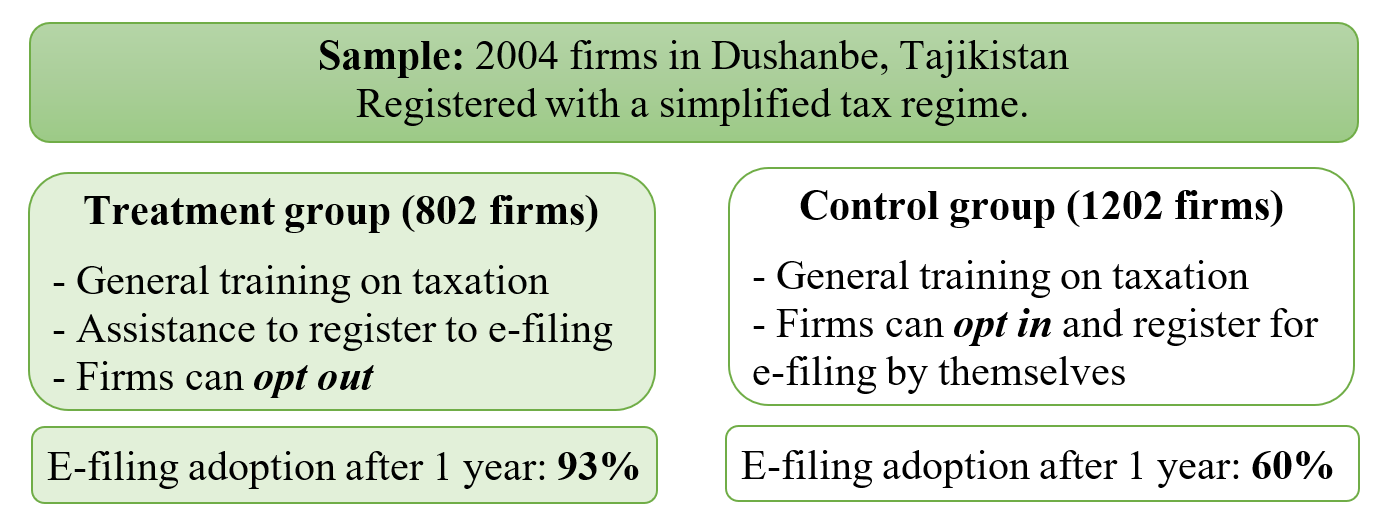

We implemented a randomised experiment whereby we provided a randomly selected group of firms with in-depth training on e-filing and assistance completing extensive e-filing registration requirements. Firms in this group must explicitly opt out of e-filing if they do not want to use it. 93% of firms in this group adopt e-filing, versus 60% in the comparison group, where firms must opt in and complete the registration process by themselves. We use this difference in adoption rates to estimate the impact of e-filing adoption on firms.

Figure 1: A randomised experiment with an encouragement design to promote e-filing adoption

E-filing reduces tax compliance costs by 40%

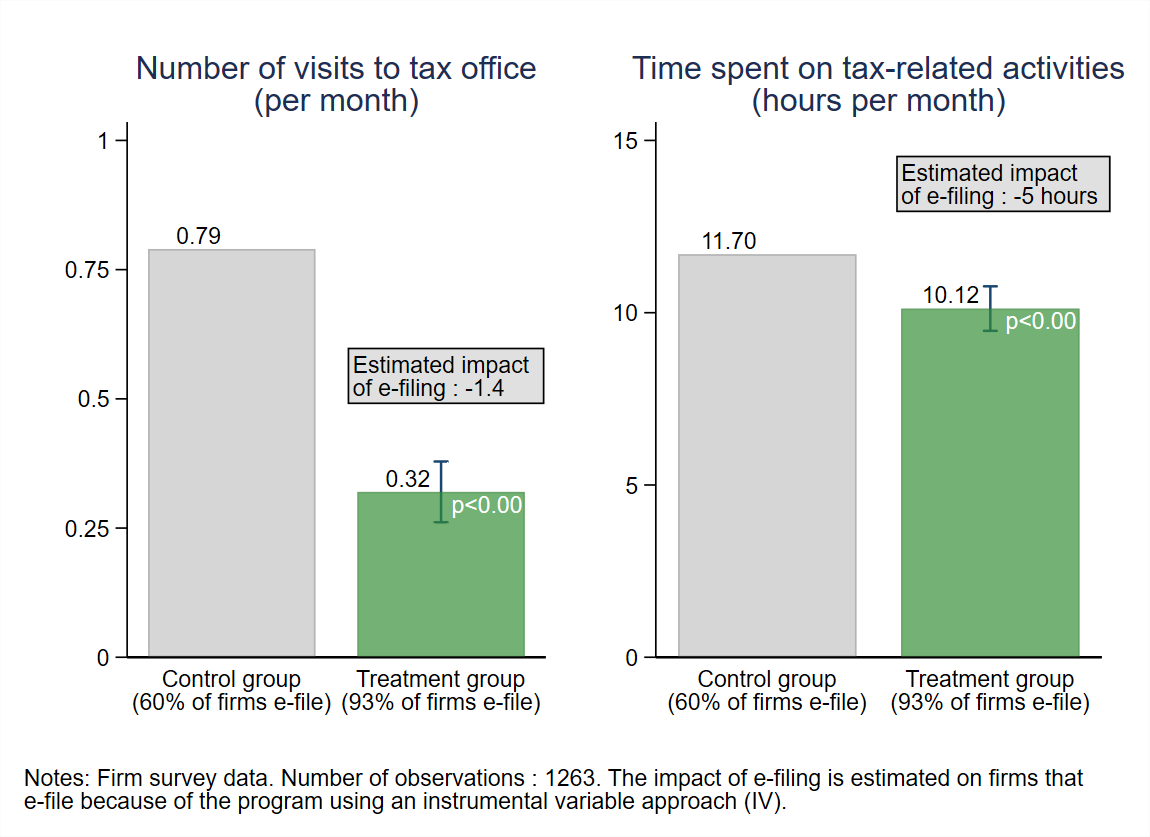

Firms in the treatment group visit the tax office 0.47 fewer times each month. Adjusting this for the difference in adoption rates in treatment and control groups, we find that firms that e-file as a result of the programme visit the tax authority 1.4 times fewer in a year. Similarly, firms in the treatment group spend 1.58 fewer hours on tax-related activities, amounting to savings of almost five hours a month for firms that e-file due to the programme – a 40% reduction.

On the part of the tax authority, back-of-the-envelope calculations indicate that, at current e-filing rates, the tax authority frees up over 5,800 tax-official-hours each month that can be reallocated to other activities likely higher in marginal productivity than receiving tax declarations.

A ‘naïve’ cost-effectiveness analysis comparing programme costs to the amount of money firms save from lower compliance costs (using the average wage of an accountant in our sample) shows that potential benefits from reducing compliance costs more than compensate programme costs after seven months.

Figure 2: Impact of e-filing on tax compliance costs

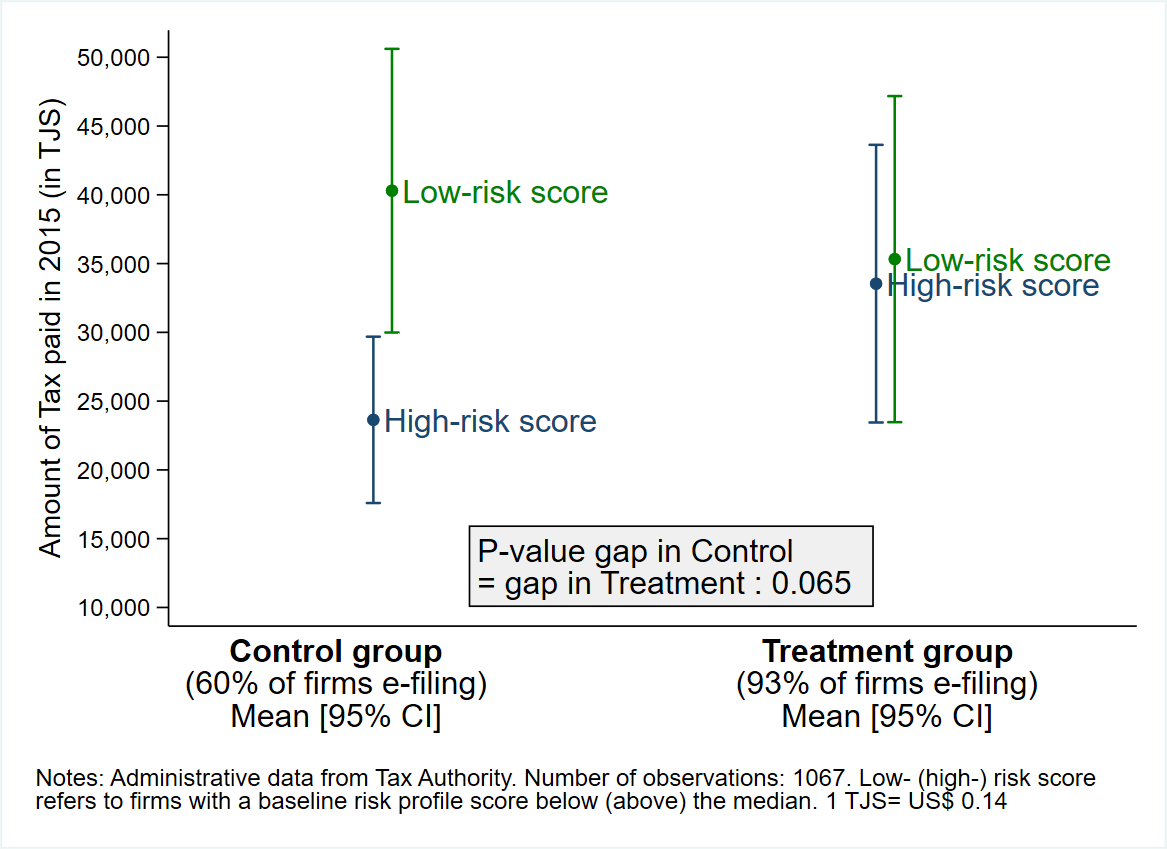

E-filing does not meaningfully change the total amount of taxes paid, but it does change the distribution of tax payments across firms by their likelihood of tax evasion at baseline

Firms flagged by the tax administration as likely evaders before the programme, measured using a risk profile score, pay more taxes. Administrative data on the total amount of tax paid for the year reveals an increase of TJS 25,737 (US$3,680) as a result of e-filing among firms with above-median risk scores for tax evasion – a 108% increase relative to the control group. In contrast, among firms with below-median risk scores, e-filing adoption results in firms paying TJS 15,930 (US$2,280) less in taxes (a 40% reduction). E-filing thus closes the tax payment gap between firms with below-median risk scores and those with above-median risk scores (see Figure 3), and this result is robust to adjusting for other firm characteristics besides the risk profile score.

Figure 3: Impact of e-filing on tax paid, by risk profile score (Intent-to-treat results)

Firms flagged as less likely to evade tax pay fewer bribes, presumably because e-filing reduces extortion opportunities

We use a list experiment to measure bribe payments in our endline survey to minimise reporting bias by guaranteeing anonymity (Kuklinski et al. 1997). We find opposite results for firms in the two risk score categories. We find a large and statistically significant reduction in bribes (59 percentage points) for firms with below-median risk scores. However, for firms with above-median risk scores, estimates are imprecise, and we cannot rule out large positive or negative effects.

Mechanisms

These results on tax payments and bribes are consistent with differential treatment of firms by tax officials prior to e-filing. Our interpretation, supported by interviews, is that under paper filing, high-risk firms collude with tax officials to reduce tax liabilities. On shifting to e-filing, they lose this benefit, and their tax payments increase. This interpretation is supported by striking patterns in the selection of firms into e-filing adoption. Among the control group, after adjusting for firm characteristics, we find that a one standard deviation increase in a firm’s risk score is associated with a seven percentage point decrease in its likelihood of adopting e-filing. Firms with higher risk score are also prone to revert to paper filing after e-filing adoption.

For firms with a lower risk score, there are two potential explanations for the lower payments. First, under paper filing, officials may have used private information to enforce compliance of firms’ true liability; with e-filing, firms experience less direct monitoring and evade more. Second, as some firms claim, officials may have required firms to pay beyond their true liability to meet their revenue targets; e-filing relieves this pressure.

Policy implications

These findings offer valuable insights for other technologies designed to increase efficiency and reduce corruption:

- Selection among potential users is a crucial determinant of the outcome. Those anticipating negative effects from new technology due to expected behaviour constraints may be the least likely to adopt. However, this may be the population of greatest interest. As a result, when deciding whether to make new technologies mandatory, governments should carefully weigh the capacity constraints of potential users in adopting new technology, with the potential of those with a high risk of non-compliance opting out.

- Technology can produce heterogeneous effects. The impact of technology introduced to replace human discretion depends on how discretion was previously exercised. If discretion produces worse outcomes, technology may improve outcomes (as we find with increased tax payments among firms with higher risk scores and lower bribe payments among firms with lower risk scores). However, if discretion produces desirable outcomes (such as the monitoring of firms), technology may inadvertently produce less desirable outcomes.

Editor’s note: This paper received the 2023 American Economic Association's Best Paper of the Year Award in American Economic Journal: Economic Policy.

References

Banerjee, A, E Duflo, C Imbert, S Mathew, and R Pande (2020), “E-governance, Accountability, and Leakage in Public Programs: Experimental Evidence from a Financial Management Reform in India”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 12(4): 39–72.

Besley, T, and T Persson (2014), “Why Do Developing Countries Tax So Little?”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 28(4): 99–120.

Gordon, R, and W Li (2009), “Tax Structures in Developing Countries: Many Puzzles and a Possible Explanation”, Journal of Public Economics 93(7–8): 855–66.

Kuklinski, J H, P M Sniderman, K Knight, T Piazza, P E Tetlock, G R Lawrence, and B Mellers (1997), “Racial Prejudice and Attitudes toward Affirmative Action”, American Journal of Political Science 41(2): 402–19.

Lewis-Faupel, S, Y Neggers, B A Olken, and R Pande (2016), “Can Electronic Procurement Improve Infrastructure Provision? Evidence from Public Works in India and Indonesia”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 8(3): 258–83.

Muralidharan, K, P Niehaus, and S Sukhtankar (2016), “Building State Capacity: Evidence from Biometric Smartcards in India”, American Economic Review 106(10): 2895–2929.

Okunogbe, O, and V Pouliquen (2022), "Technology, Taxation, and Corruption: Evidence from the Introduction of Electronic Tax Filing", American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 14(1): 341-72.