Electronic payment cards leave a digital trail that can be used for tax enforcement, but tax compliance may not increase if firms also trade in cash

Editor's Note: For more on tax compliance read the VoxDevLit on Taxation and Development.

The adoption of electronic payment technologies (EPTs) like credit cards, debit cards, mobile money, and payment apps has long been hailed as a way to formalise transactions, increase tax compliance, and strengthen state capacity (e.g. Rogoff 2017, Das et al. 2023). EPTs generate an electronic trail that governments can potentially leverage to detect unreported income (Kleven et al. 2011, Pomeranz 2015, Naritomi 2019). However, whether the digitisation of transactions actually increases tax compliance crucially depends on how both firms and consumers use EPTs, and on the share of transactions that are conducted digitally.

In our new research, (Brockmeyer and Somarriba 2024), we leverage variation from Uruguay’s financial inclusion reforms to examine the effect of financial incentives on the take-up of EPTs among firms and consumers, and on the tax compliance behaviour of firms.

Uruguay’s financial inclusion reforms

Uruguay is an ideal context for our study. The country long lagged behind peer countries in key financial inclusions measures. It also faced tax compliance challenges, with VAT evasion estimated to be twice as high as in advanced economies. Policymakers thus saw potential for a “big-push” financial inclusion reform that could also help combat evasion and strengthen tax capacity.

In 2014, the government adopted a set of measures to deepen financial inclusion, including the provisions of free bank accounts with payment cards, reduced commissions and fees for electronic payments, and an improved policy environment for payment network companies. Our study examines the effect of a rebate on the value-added tax (VAT) that was offered from August 2014 to all consumers paying with a debit or credit card. The rebate rate was 2-4 percentage points, depending on the type of payment card used and the transaction amount. Given the moderate VAT rates of 10% and 22%, these rebates represent a tax reduction of up to 40% for consumers. The rebates were also highly salient and hassle-free. Consumers paid the discounted price upfront and obtained the rebate instantly at the point of sale.

Combining the timing of the introduction of the rebates on August 1, 2014, with daily transaction-level data and firm-level VAT records allows us to examine the impact of the rebates on consumers’ use of payment cards, firms’ use of POS machines, and firms’ tax compliance.

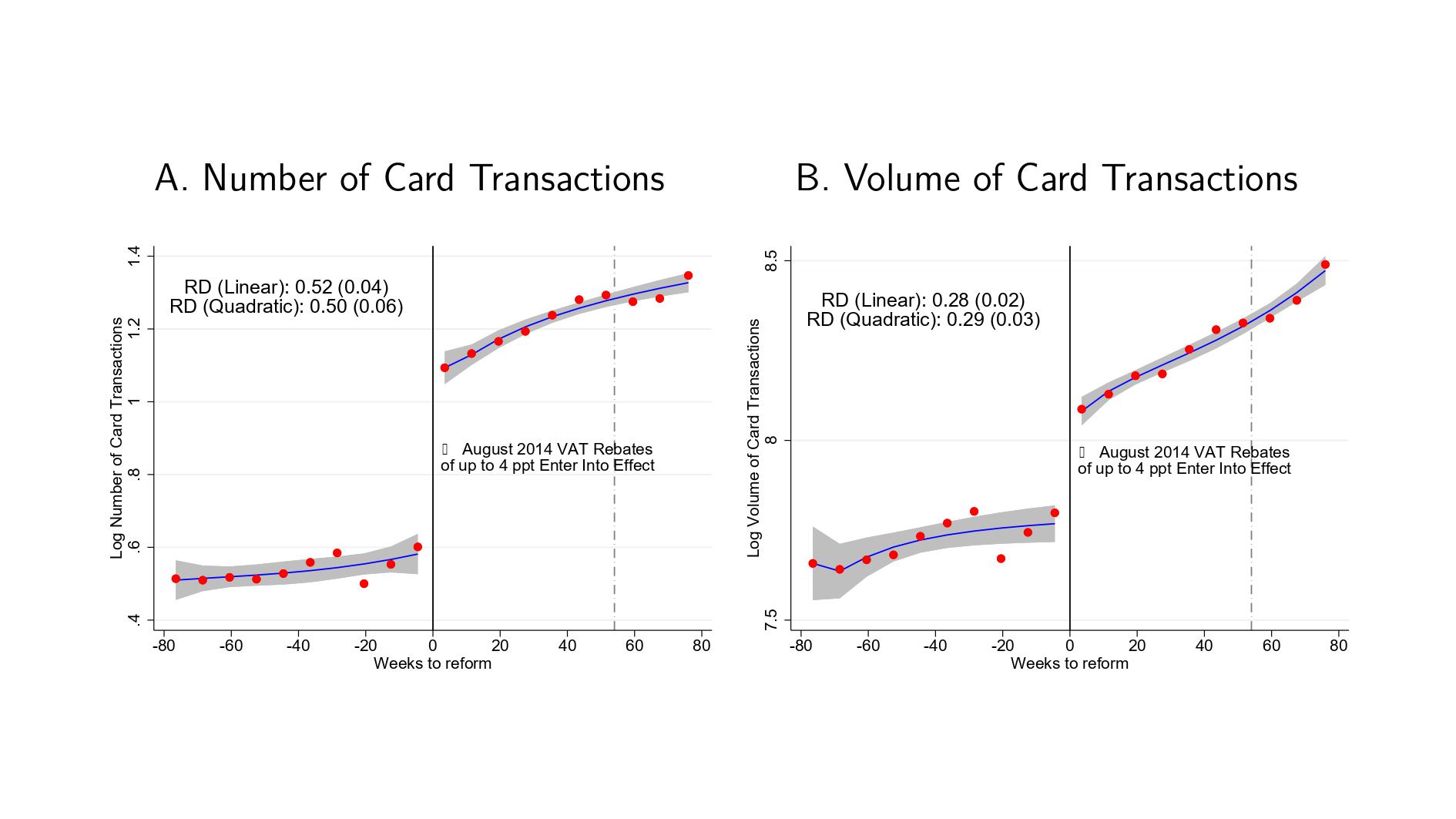

Figure 1: Consumers’ response to the introduction of VAT rebates

Note: The figure shows results of a regression discontinuity estimation in time around August 1, 2014 (time=0, solid vertical line) when the VAT rebates were introduced. The dotted vertical line marks August 1, 2015, when the VAT rebate rates were reduced.

Consumers increased the use of debit and credit cards

We first demonstrate (using a regression discontinuity in time) that consumers responded very strongly to the introduction of VAT rebates. The number of debit and credit card transactions jumped by 50% in August 2014 compared to the previous trend. The volume of card transactions increased by about 30%. Consumers hence appear highly sensitive to financial incentives for the use of electronic payments (Figure 1). The effect emerges precisely when rebates are introduced in August 2014, after stable pre-reform trends. The immediate response is consistent with the salient nature of the incentives.

When the rebate rates were lowered in August 2015, there was no decline in card use. This suggests that temporary incentives can have a lasting impact on consumer behaviour.

Firms’ use of point-of-sales terminals did not increase

As consumers increased the use of payment cards, one might in turn expect firms to increase the use of point-of-sales terminals, to ensure they can offer their consumers the option of paying by card. Using the same regression discontinuity design as in the consumer analysis, we find that little evidence for POS adoption by firms. The number of firms with at least one point-of-sale (POS) terminal did not increase when the rebates were introduced. Only firms that already had a POS prior to the reform increased POS usage, by using a larger number of POS terminals.

These results are consistent with the fact that using a POS is costly for firms that are not yet fully tax compliant. Previously unreported cash transactions can be revealed through the POS’s digital paper trail. Indeed, in monthly event studies, we find that VAT liabilities increase sharply when firms use a POS terminal for the first time.

We also show that small subsidies for POS usage and reductions in card fees did little to incentivise POS adoption. The results imply that much larger financial incentives, or a mandate may be needed to spur extensive margin POS adoption.

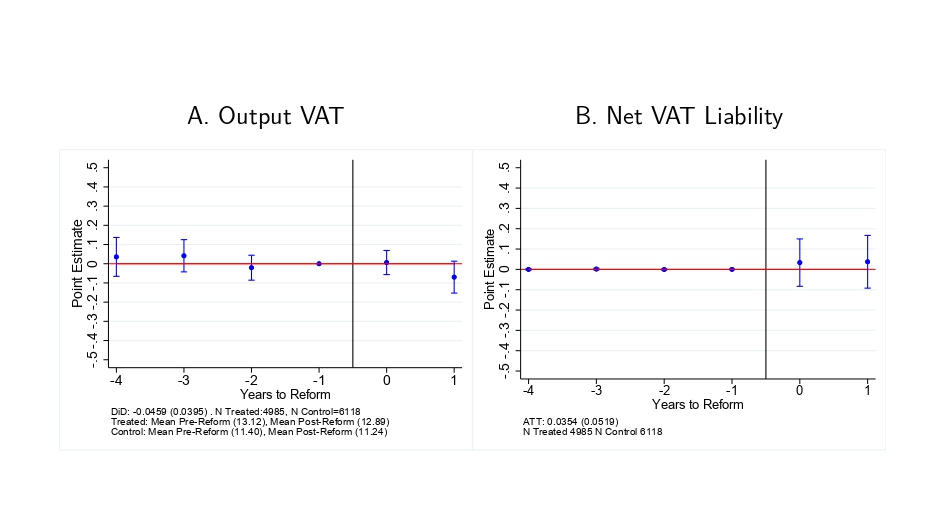

Tax compliance was not affected

To assess the effect of the VAT rebates on tax compliance, we compare retail firms with a POS, who benefited directly from the rebates, to wholesale firms (using a difference-in-difference design). Retailers are usually among the least tax compliant segments of the formal sector, and they are directly affected by the reform as their consumers switch from paying in cash to paying by debit or credit card. Wholesale firms, however, should be unaffected by the reform.

We find that wholesale firms are indeed a good control group for retailers, as their trend in totals sales and tax liability over time is very similar to the trend for retailers. Contrary to the hypothesis that a digitixation of transactions improves tax compliance, we find no increase in compliance among retailers after the reform (Figure 2). We estimate precise zero effects of the introduction of VAT rebates on our key outcome variables – the output VAT and the net VAT liability. As the government granted VAT rebates to consumers while firms did not increase their reported taxable transactions or income, the incentives generated a net fiscal cost of 1.5% of VAT revenue.

Figure 2: Tax compliance effect of VAT rebates

Notes: The figure shows point estimates from a difference-in-difference estimation comparing retail firms with a POS to wholesale firms without a POS, around the year of the introduction of VAT rebates, marked by the vertical line. The panel titles show the outcome variables.

What explains the zero effect on tax compliance?

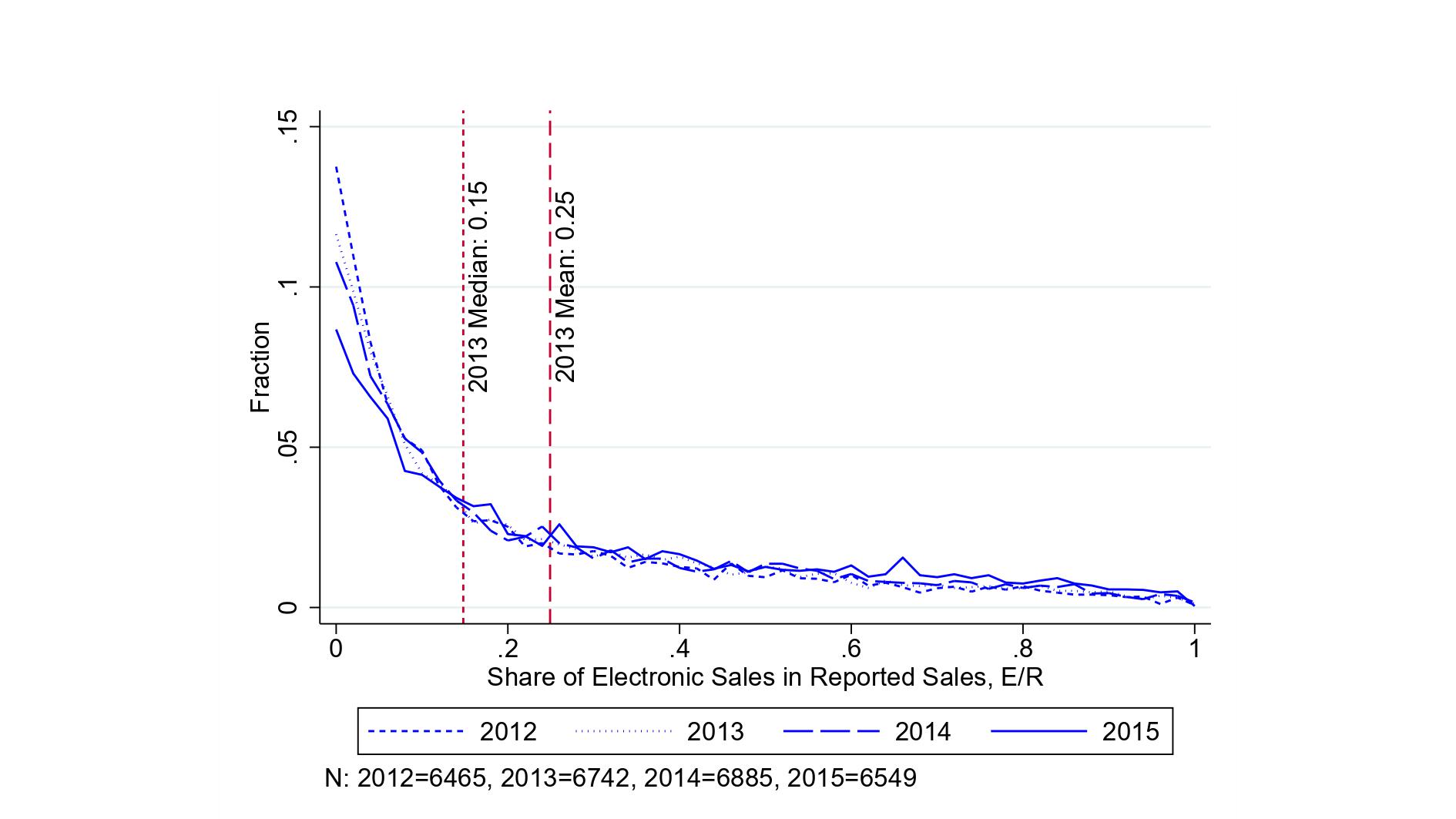

Zooming in on firm behaviour helps rationalise the results. First, self-selection into POS adoption meant that only relatively compliant firms had a POS and hence experienced an increased in card transactions when the VAT rebates where introduced. Second, among firms with a POS, card sales covered only 15-25% of total reported sales before rebates (Figure 3). So firms seemed to have already reported a large share of cash transactions, leaving room to increase card transactions without raising reported sales.

Figure 3: Distribution of the share of card transactions in total sales

Notes: This figure shows the distribution of the share of card transactions in total sales among firms with a POS. The mean and median displayed with the red lines are for the year 2013.

What are the wider lessons from Uruguay’s experience with VAT rebates? The results demonstrate that consumers readily increase their usage of EPTs in response to financial incentives. The policy is hence successful in fostering digitalisation. However, EPT-based VAT rebates on their own are a regressive policy, as richer households are more likely to hold EPTs and shop at retailers with POS terminals. More research is needed to design temporary, targeted incentives that maximise EPT use at minimal fiscal cost and in a progressive manner. New ideas and analysis are also needed to identify policies that can encourage POS adoption among firms.

Our study does not deny that the digitalisation of payments has the potential for strengthening tax capacity. But it highlights that the actual impact of digitalisation depends on behavioural responses on both the supply and the demand side of the market, and crucially hinges on the share of transactions covered by digital paper trails.

References

Brockmeyer, A and M Saenz Somarriba (2024), “Electronic Payment Technology and Tax Compliance: Evidence from Uruguay’s Financial Inclusion Reform”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, forthcoming.

Das, S, Gadenne, L, Nandi, T, and R Warwick (2023), "Does going cashless make you tax-rich? Evidence from India’s demonetization experiment", Journal of Public Economics, 224: 104907.

Kleven, H J, Knudsen, M B, Kreiner, C T, Pedersen, S, E and Saez (2011), "Unwilling or unable to cheat? Evidence from a tax audit experiment in Denmark", Econometrica, 79(3): 651-692.

Naritomi, J (2019), "Consumers as tax auditors", American Economic Review, 109(9): 3031–3072.

Pomeranz, D (2015), "No Taxation without Information: Deterrence and Self-Enforcement in the Value Added Tax", American Economic Review, 105(8): 2539–2569.

Rogoff, K (2017), "The curse of cash: How large-denomination bills aid crime and tax evasion and constrain monetary policy", Princeton University Press.