Firms displayed considerable agility in reshoring domestic trade across states following the closure of state borders in India during the COVID-19 pandemic. Those more affected by the shock persistently increased sales and input procurement within their home state.

Recently, global supply chains have been increasingly hit by a series of shocks (Baldwin et al. 2023a, 2023b) such as the pandemic, wars, closure of trading routes and tariffs. Input sourcing gets delayed, and sales are frequently affected by these disruptions (Bai et al. 2024a, 2024b). How do firms deal with this rising uncertainty in both upstream and downstream markets? Do they scale down production, or adapt to the shock by finding new markets and suppliers? How persistent are these changes?

Our recent research (Chakrabarti et al. 2024) sheds light on how firms respond to such unexpected shocks in the context of the COVID-19 lockdown in India, which led to the closure of state borders in the country. Specifically, we find that (a) firms more affected by the shock persistently increase sales and input procurement within their state, and (b) the extent to which this reshoring is possible depends on a novel product-level measure, Scope for Home Expansion (SHE).

Disruption of inter-state trade in India during COVID-19

We exploit the state border closures implemented during the first national lockdown at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in India. The closures were announced by the central government on March 24, 2020 with immediate effect. Transportation of all non-essential commodities across the states (other than food and pharma products) was completely curtailed during the lockdown. The timing and stringency of these measures were unanticipated by firms. Due to the border closures, both input sourcing and sales to regions outside the home state were disrupted until April 2020. We examine how firms responded to this temporary closure of state borders after the restrictions were removed.

To do this, we use novel administrative data collected by the Goods and Services Tax Network in India, namely the E-Way Bills, for the period 2019-2020. This data is reported at monthly frequency with information on sales and input sourcing by firms located in 35 regions (or states) across India. For each state, we observe sales and input-sourcing data at firm-level, both inside the home state (intra-state) and outside the home state (inter-state). Similar data is available for products across all states at HSN 4-digit level.

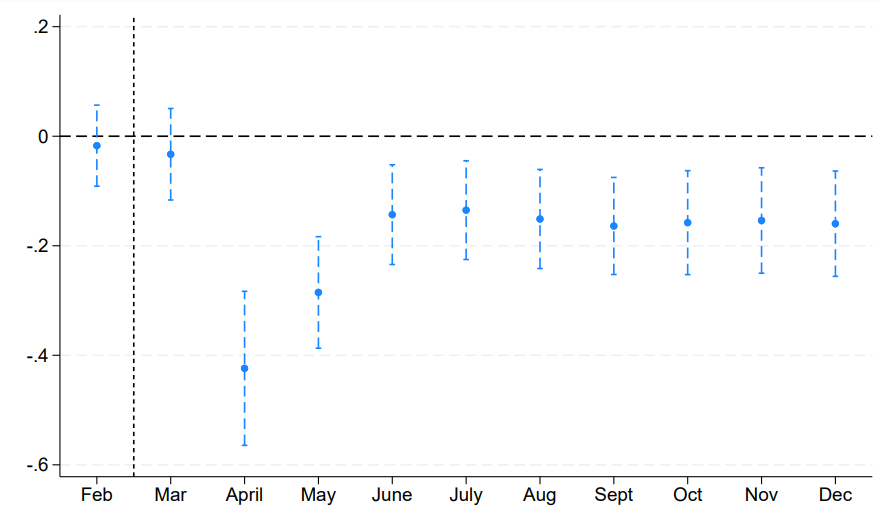

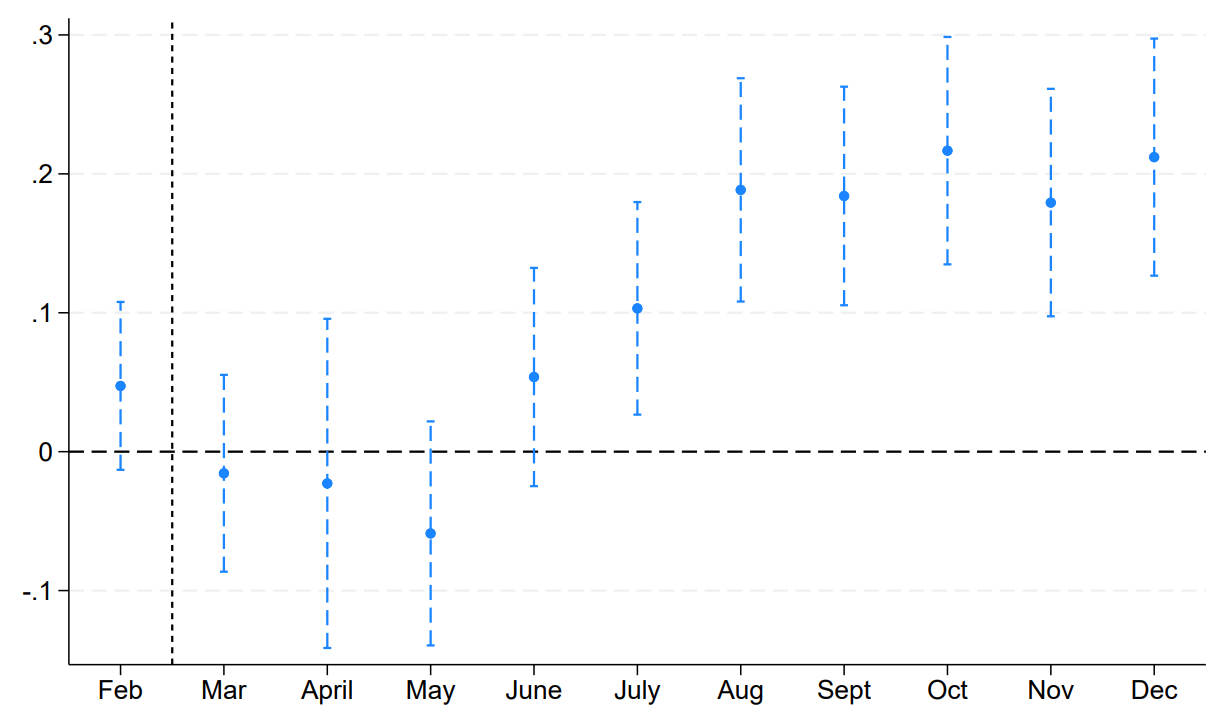

Figure 1: Reshoring in firm sales

(a) Inter-state sales (b) Intra-state sales

Notes: This figure shows two panels illustrating the reshoring of sales from inter-state to intra-state, for every month in 2020 with January 2020 as the base month, relative to change between the same months in 2019. The vertical dashed line marks the beginning of the lockdown. Inter-state sales (Panel (a)) fall and remain persistently below the pre-lockdown levels throughout the year while intra-state sales (Panel (b)) witness a persistent increase, albeit with a lag, for firms having higher exposure to inter-state sales before the pandemic.

Reshoring in domestic trade across Indian states

We use a difference-in-differences strategy where we compare monthly firm-level outcomes before and after the lockdown as a function of their reliance on inter-state trade before the shock. Our hypothesis posits that firms with relatively greater inter-state dependence would be more adversely hit by the border closures than those selling within the home state and would be more likely to reshore sales.

We find evidence for reshoring in sales – a 6% decline in inter-state sales and a simultaneous 8% increase in intra-state sales for a one-standard-deviation increase in plants’ inter-state sales dependence until December 2020 (Figure 1). Inter-state sales fall immediately in April, recover partially by June 2020, but remain below the pre-lockdown levels until the end of the year. The intra-state sales show opposite trends with minimal effects until June, after which they increase and stabilise at higher values. We find similar reshoring in the case of input-sourcing as well.

Given our methodology, and the granularity of data we have access to, we can rule out that these effects reflect monthly seasonality or sector-specific demand shocks. Other firm-specific factors, such as pre-lockdown financial conditions, do not explain the observed reshoring.

‘Vent-in’ trade after disruption to inter-state trade

These results support firm-level reshoring after the shock – firms unable to trade outside the state during the temporary border closures, shift to sales and input-sourcing within the home state. We also demonstrate that state borders are the salient administrative boundaries influencing firm choice of where to buy and sell, and not geographical distance. Our results are parallel, but work in the opposite direction, to the “vent-for-surplus” channel observed by Almunia et al. (2021). They find that firms which sell both at home and abroad, redirect sales to international markets after a decline in local demand, effectively ‘venting out’ additional production to export markets. In our case, firms restricted from accessing inter-state markets during the temporary lockdown phase, “vent in” or redirect excess production to the home market.

Finding local markets: Scope for home expansion

Next, we examine the product characteristics that allow for such reshoring. We define a new measure, Scope for Home Expansion (SHE), that captures the reshoring potential of a product. Intuitively, for a given product, this measure captures the extent to which the local market can absorb the prior production directed at inter-state sales by substituting the same product imported from other states. To illustrate, consider Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, two states in India that both sell coffee at home and to each other. When a disruption, like the border closure occurs, each state has the possibility to substitute externally sourced coffee with home state production. This allows inter-state sales of coffee to be redirected towards sales at home. Such substitution would be less likely for products like iron-ore, which only Tamil Nadu produces and sells in both states. In this case, Tamil Nadu’s inter-state iron-ore sales cannot be redirected internally. This idea is captured by the proposed Scope for Home Expansion measure. States with a high average value of Scope for Home Expansion can easily absorb the prior production directed at inter-state sales to intra-state sales.

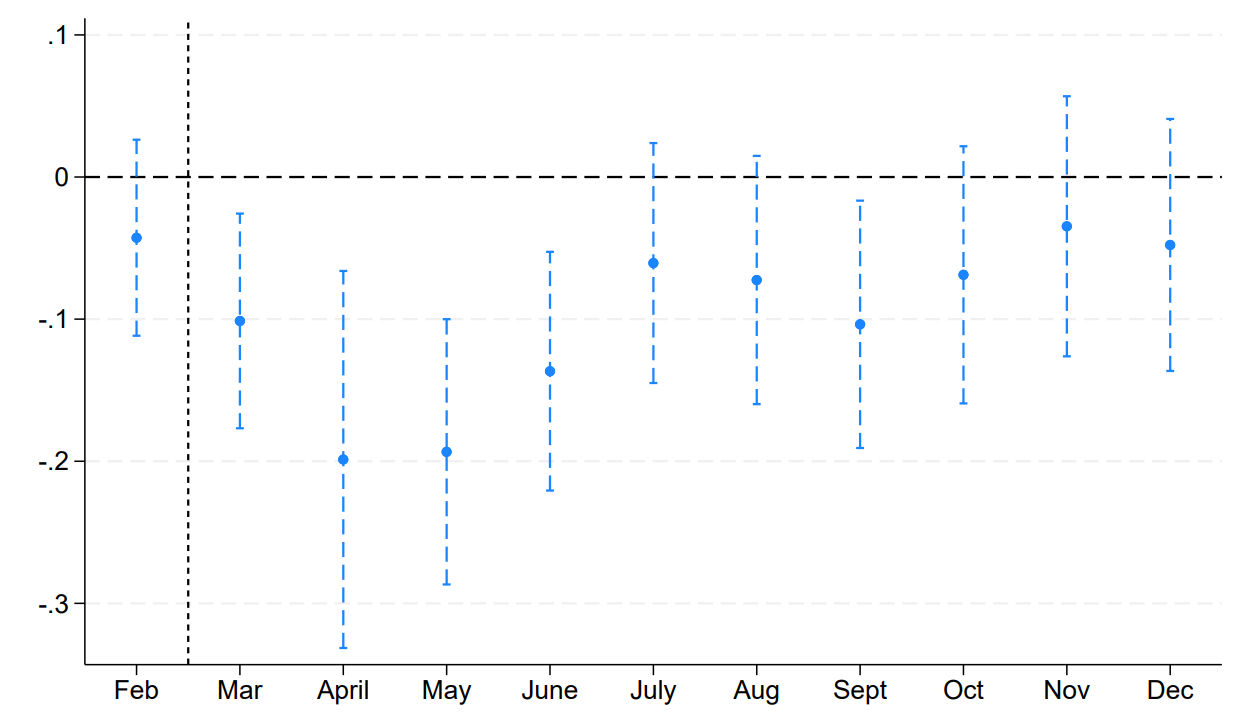

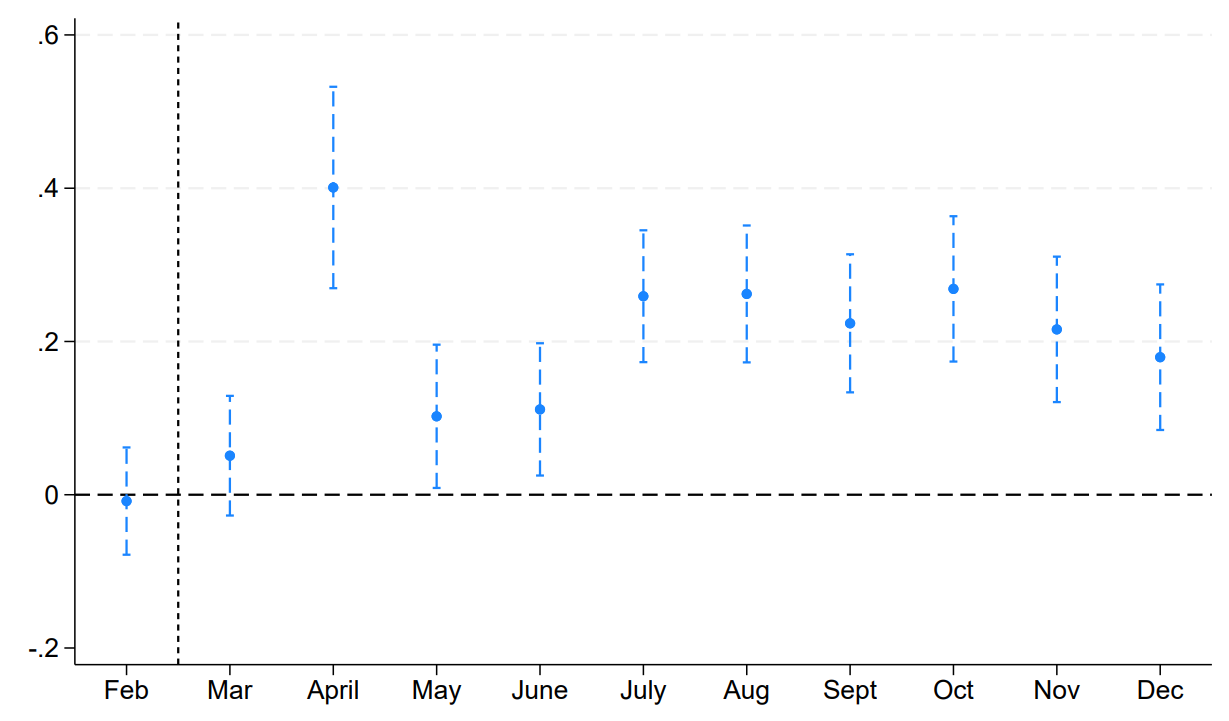

We compute the Scope for Home Expansion measure for each product-state and assess the heterogeneity in sales recovery based on this metric. Figure 2 shows that products with high Scope for Home Expansion witness a fall in inter-state sales and an increase in intra-state sales, beyond the initial shock during the lockdown. This shows a persistent shift from inter-state to intra-state sales, for products having a higher Scope for Home Expansion, consistent with the intuition described above. Given their production and trade within the home state and across state borders, states differ significantly in terms of Scope for Home Expansion. This leads to substantial variation in their reshoring potential.

Figure 2: Scope for home expansion and reshoring

(a) Inter-state sales (b) Intra-state sales

Notes: This figure shows that products having a higher Scope for Home Expansion witness larger reshoring. The two panels above illustrate the heterogeneous impact on inter-state (Panel (a)) and intra-state (Panel (b)) sales of a product originating in a state by product-state level SHE. respectively, for every month in 2020 with January 2020 as the base month, relative to change between the same months in 2019. The vertical dashed line marks the beginning of the lockdown.

Concluding remarks on supply chains after disruptions

Our work adds to the recent research on supply chain vulnerability and firm responses to mitigate these risks. This problem has attracted both academic (Barrot and Sauvagnat 2016, Carvalho et al. 2021) as well as practitioners’ attention (Business Continuity Institute’s reports 2019, 2021). There are several potential mechanisms that improve firm agility to survive trade disruptions – the ability to redirect production captured through the Scope for Home Expansion measure is one such determinant. Amid rising uncertainty and protectionism, our findings have implications for international trade. While we have provided evidence on the main determinants of reshoring in the domestic trade context, our findings suggest that disruptions can lead to re-organisation of supply chains based on production-import-export baskets across countries.

References

Baldwin, R, R Freeman, and A Theodorakopoulos (2023a), “Hidden exposure: Measuring US supply chain reliance,” NBER Working Paper, No. 31820.

Baldwin, R, R Freeman, and A Theodorakopoulos (2023b), “Supply chain disruptions: Shocks, links, and hidden exposure,” VoxEU column, https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/supply-chain-disruptions-shocks-links-and-hidden-exposure.

Bai, X, J Fernández-Villaverde, Y Li, and F Zanetti (2024a), “The causal effects of global supply chain disruptions on macroeconomic outcomes: Evidence and theory,” NBER Working Paper, No. 32098.

Bai, X, J Fernández-Villaverde, Y Li, and F Zanetti (2024b), “The causal effects and policy implications of global supply chain disruptions,” VoxEU column, https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/causal-effects-and-policy-implications-global-supply-chain-disruptions.

Chakrabarti, A S, K Mahajan, and S Tomar (2024), “Trade disruptions and reshoring,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics (forthcoming).

Almunia, M, P Antràs, D Lopez-Rodriguez, and E Morales (2021), “Venting out: Exports during a domestic slump,” American Economic Review, 111: 3611–3662.

Barrot, J-N, and J Sauvagnat (2016), “Input specificity and the propagation of idiosyncratic shocks in production networks,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131: 1543–1592.

Carvalho, V M, M Nirei, Y U Saito, and A Tahbaz-Salehi (2021), “Supply chain disruptions: Evidence from the great east Japan earthquake,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 136: 1255–1321.