Green trade policy for palm oil can greatly reduce emissions for an industry that is pivotal in the fight against climate change

Palm oil is ubiquitous, with uses ranging from cooking and baking to cosmetics and biofuels. It is among the most widely used plant products in the world today. Palm oil largely comes from Indonesia and Malaysia, which produce the commodity and export it widely. In these countries, the industry has fueled economic growth and lifted millions out of poverty (Edwards 2019).

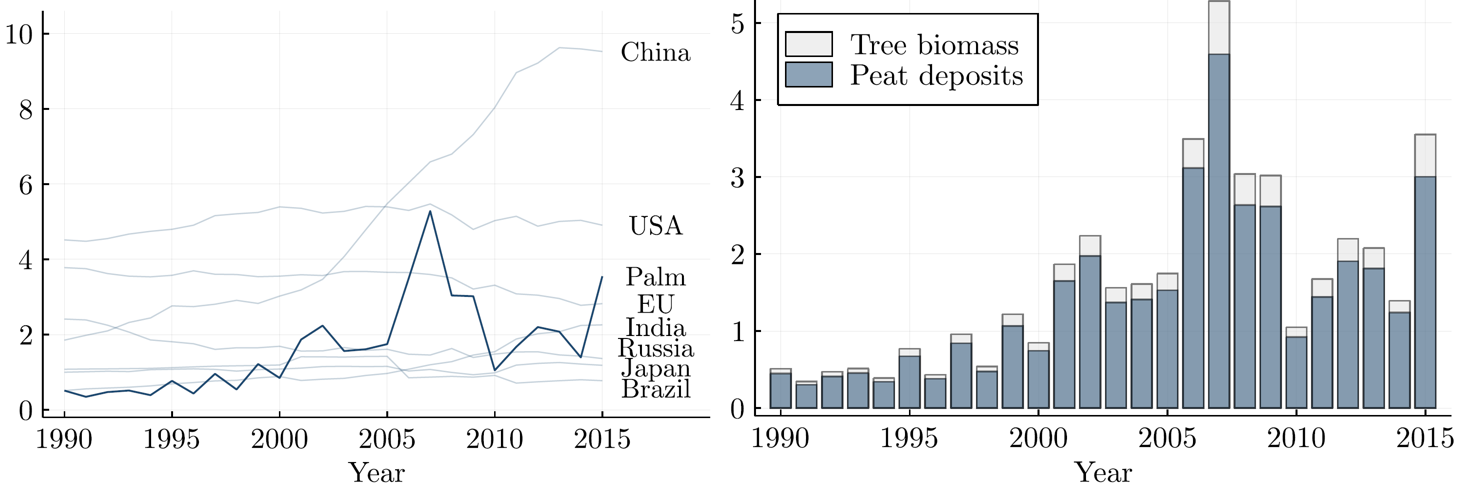

At the same time, land clearing for palm oil plantations has driven large-scale deforestation across Indonesia and Malaysia, where peatland forests store vast amounts of carbon. These swampy forests sit atop deep layers of decomposing organic material called peat, which forms in layers over the course of millennia. The slashing and burning of these forests, which contain peat layers up to 10 metres deep, accounts for more carbon emissions than the entire Indian economy from 1990 to 2016 (Hsiao 2024). Figure 1 shows that these emissions are large, even in comparison to emissions from China, the US, and Brazil, and that they are driven by peat destruction.

Figure 1: Palm oil emissions (1990 to 2016)

Notes: The left figure compares Indonesian and Malaysian palm oil to the top emitters, accounting for land-use change. Palm emissions are 4.95% of global emissions from 1990 to 2016. The right figure decomposes palm emissions from tree biomass and peat deposits. Emissions are in gigatons of CO2 equivalents.

In response, the European Union has considered import tariffs on palm oil (OJEU 2018). In Hsiao (2024), I evaluate these tariffs as a means of environmental regulation. I build a dynamic empirical model of the world market for palm oil, and I estimate it with fine-grained data on palm oil consumption and production over space and time. I use the model to simulate regulation in the form of production taxes, import tariffs, export taxes, and a carbon border adjustment mechanism. I quantify impacts on emissions and global welfare, and I draw lessons for green trade policy more broadly.

Regulatory policies for palm oil

Production taxes target palm oil production through direct regulation. This direct approach is most efficient, but it relies on domestic capacity to regulate. I find that a 50% production tax in Indonesia and Malaysia would have reduced palm oil emissions by 7.5 Gt of CO2 equivalents from 1988 to 2016. The tax raises world prices for palm oil, reducing consumer surplus worldwide. Lower demand for palm oil then reduces producer surplus in Indonesia and Malaysia. But the tax also allows these countries to exercise their market power, raising government revenue at the expense of foreign consumers. Total welfare rises for Indonesia and Malaysia, even as emissions fall.

Import tariffs target palm oil consumption in world markets. This indirect approach is less efficient than directly taxing production, as Indonesian and Malaysian consumption remains untraded and thus unregulated. But import tariffs do not rely on domestic capacity to regulate, and indeed rural plantations are difficult to monitor individually. Relative to 7.5 Gt under domestic production taxes, I find that import tariffs of similar magnitude would have reduced palm oil emissions by up to 5.4 Gt. This reduction amounts to nearly five years of Indian emissions. Import tariffs are most effective with full coordination across importers and full coordination to uphold tariffs over the long run. Emission reductions fall far short of 5.4 Gt when coordination and commitment fail.

Export taxes can achieve the same emission reductions as import taxes, to the extent that both cover traded goods. I show that Indonesia and Malaysia would prefer export taxes, which avoid taxing domestic consumers and shift the tax burden to foreign consumers. Like domestic production taxes, export taxes allow Indonesia and Malaysia to exercise market power, improving their total welfare while also reducing emissions. Unlike domestic production taxes, which require on-the-ground monitoring, export taxes require enforcement only at international ports.

A carbon border adjustment mechanism combines import tariffs with credits for domestic regulation. The problem is that import tariffs undercut incentives for Indonesia and Malaysia to tax production domestically, as import tariffs shift the burden of production taxes onto domestic consumers. Even with modest import tariffs of 25%, Indonesia and Malaysia experience welfare losses at all levels of domestic production taxes. Credits for domestic regulation restore incentives for domestic regulation, again allowing Indonesia and Malaysia to reduce emissions while also increasing their total welfare.

General lessons for green trade policy

First, trade policy is most effective when countries can coordinate and commit to long-run regulation. Unilateral measures are less effective because they are undercut by leakage to unregulated markets. Short-run measures are less effective because firms continue to invest in brown technology if they anticipate that environmental regulation is temporary.

Second, green trade policy need not be punitive. Compensating transfers can promote equity and acknowledge the global good that targeted markets provide in curbing local emissions. For palm oil, EU import tariffs lead to large economic losses for Indonesia and Malaysia. The EU should recognise these losses and rebate tariff revenues to Indonesia and Malaysia. Such transfers act as payments for ecosystem services at national scale. I find the marginal abatement cost of EU-led import tariffs to be as low as $15 per ton, even inclusive of these compensating transfers.

Third, targeted markets may themselves have fiscal incentives to regulate, even independent of emission concerns. Market power encourages domestic production taxes or export taxes, with the latter avoiding taxation of domestic consumers. For palm oil, Indonesia and Malaysia can achieve more than 10 Gt of carbon abatement while simultaneously increasing their total welfare, subject to domestic capacity to enforce regulation. Green trade policy should maintain these domestic incentives to regulate, and a carbon border adjustment mechanism is one approach to doing so.

Green trade policy for palm oil can greatly reduce emissions for an industry that is pivotal in the fight against climate change. Despite the economic gains from palm oil production, the emissions from palm-related deforestation call for stronger regulation, particularly for carbon-rich peatland forests. Damages from forest fires exemplify the need for regulation (Balboni et al. 2023). At the same time, policymakers must also recognise the global ecosystem services that Indonesia and Malaysia provide in curbing deforestation. Policy action should aim toward a future that is both sustainable and equitable.

References

Balboni, C, R Burgess and B Olken (2023) "The Origins and Control of Forest Fires in the Tropics."

Edwards, R (2019), "Export Agriculture and Rural Poverty: Evidence from Indonesian Palm Oil."

Hsiao, A (2024), "Coordination and Commitment in International Climate Action: Evidence from Palm Oil."

Official Journal of the European Union (2018) European Parliament Resolution of 4 April 2017 on Palm Oil and Deforestation of Rainforests.