Liberalising trade and FDI is key to the promotion of domestic value added into a country’s exports, as the Chinese experience highlights

In recent decades, declining trade barriers and advances in information and communication technologies have induced firms to source inputs more globally. Indeed, recent research shows a declining share of domestic content in countries’ aggregate exports, despite rising trade volume (e.g. Koopman et al. 2014, Johnson and Noguera 2016). The iPhone, which bears an engraving that says “designed by Apple in California. Assembled in China,” best exemplifies this trend. However, the iPhone’s marking only reveals the first and final steps of a long and complex production process. Over a hundred suppliers from around the world produce its various components and export them to China for final assembly. The bulk of the revenues from the iPhone’s retail sales are paid to Apple and several key multinational firms that provide its most essential inputs. Only 1.8% of the iPhone’s price is used to pay the wage bill of Chinese assembly workers (Kraemer et al. 2011).

How representative is the Apple example of China’s segment of global value chains? Do Chinese firms and workers still heavily rely on imported inputs while contributing little to the country’s exports?

Defying global trends

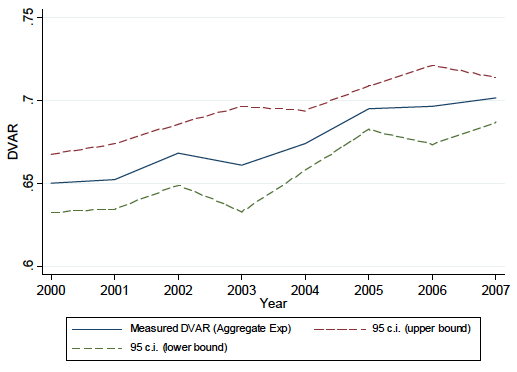

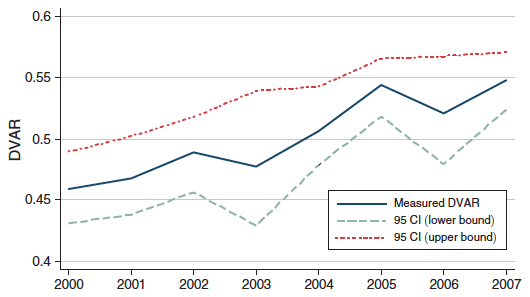

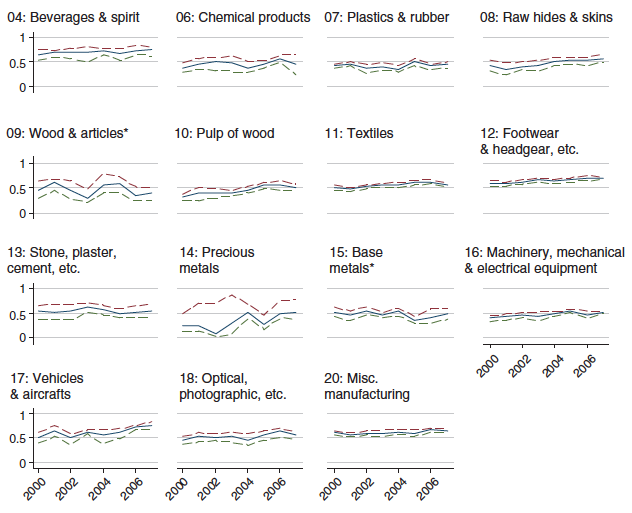

In Kee and Tang (2016), we find that China defies global trends and experiences an increasing level of domestic content in its exports since its accession to the World Trade Organization in late 2001. Using comprehensive manufacturing firm and customs transaction-level data, we systematically explore the domestic segment of global value chains in China from 2000 to 2007. We find that the share of domestic content in Chinese exports — or the ratio of domestic value added in exports to gross exports (DVAR) — has steadily increased from 65% in 2000 to 70% in 2007 (see Figure 1). The ascent of China’s processing sector is even steeper — from 46% in 2000 to 55% in 2007 (see Figure 2). Figure 3 highlights the upward trend for most industries, including the machinery, mechanical, and electrical equipment sector, which comprises of Foxconn, the company that completed the final stage of the production of Apple products.

Figure 1 DVAR of aggregate export, 2000-2007

Source: Kee and Tang (2016)

Figure 2 DVAR of processing exports, 2000-2007

Source: Kee and Tang (2016)

Figure 3 DVAR trend by industry, 2000-2007

Source: Kee and Tang (2016)

What caused China to upend the global trend of declining domestic content in exports despite its increasing participation in global value chains?

There are several possibilities. The phenomenon could be due to China’s shifting its comparative advantage from low value-added industries to high value-added industries. It could also be a result of its increasing domestic production costs. Another possibility is that firms in China may have gradually shifted their sourcing of intermediate inputs from foreign to domestic suppliers.

Our empirical evidence supports the third possibility, namely, that China’s growing domestic content in exports is due to its exporting firms gradually replacing imported inputs with domestic products. We develop a model that pins down a structural relationship between the prices of domestic materials relative to foreign materials and firms’ DVAR. We then construct the relative price index of domestic inputs using our micro data and use a 3SLS model to empirically examine how China’s tariff and foreign direct investment (FDI) liberalisations affect exporters’ DVAR. We find that the DVAR is affected through changing domestic input varieties and hence the relative prices of domestic materials.

Substitution induced by liberalisation

Our regression results show that exporting firms’ substitution of foreign inputs with domestic inputs is induced by both liberalisations in the early 2000s. Existing studies show that FDI can increase the demand for domestic materials, thus raising the supply and quality of domestic input varieties from the upstream industries due to the scale effect (Kee 2015). Tariff liberalisation, on the other hand, gives domestic suppliers access to newer, cheaper, or better imported inputs, which lowers their production costs both directly and indirectly due to endogenous improvement in productivity (Goldberg et al. 2010). As a result, external liberalisation encourages China’s intermediate input producers to expand product variety, therefore lowering domestic input prices and inducing individual processing exporters to substitute domestic for imported materials. In other words, the phenomenon of China’s 'moving up the value chain' takes place within firms.

The importance of domestic content in exports

Many developing countries have tried to implement policies to shore up the domestic content in exports. It is widely believed that higher domestic content levels would boost the economic benefits of trade, such as the trade-induced innovation and domestic input-output propagation, as an economy moves up the value chain. A higher DVAR of exports also implies a higher share of exports in a country’s GDP for a given level of aggregate exports.

These findings also lend support to recent research about the global trade slowdown after the 2008–2009 financial crisis (e.g. Constantinescu et al. 2015). When Chinese firms decide to source more inputs domestically, they trade less with the rest of the world. In a global economy characterised by roundabout input-output linkages, a reduced demand for imports from China may have substantial consequences for world trade.

Policy recommendations and concluding remarks: Liberalising trade and FDI the key

In sum, our findings suggest that liberalising trade and FDI is key to the promotion of domestic value added into a country’s exports. Policies that promote import substitution or impose domestic content requirements on exporting firms may produce counter-productive effects (e.g. World Bank, 2011). In an ongoing project, using the World Bank’s Exporter Dynamic Database to match importer-exporter customs transaction data, we employ the same method as is outlined in this paper to measure the DVAR of exports for a wide range of countries. We find an upward trend in the DVAR of exports for countries as diverse as Bangladesh, Guatemala, Madagascar, and Morocco, which all share open trade and FDI policies similar to China.

Editor’s Note: This column is part of our series on the US-China trade war. It first appeared on VoxChina in August 2017.

References

Amiti, M, O Itskhoki and J Konings (2014), “Importers, exporters, and exchange rate disconnect,” American Economic Review 104 (7): 1942–1978.

Constantinescu, C, A Mattoo and M Ruta (2015), “The global trade slowdown: Cyclical or structural?”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, WPS 7158.

Johnson, R and G Noguera (2016), “A portrait of trade in value added over four decades,” Review of Economics and Statistics, forthcoming.

Goldberg, P, A Khandelwal, N Pavcnik and P Topalova (2010), “Imported intermediate inputs and domestic product growth: Evidence from India,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 125 (4): 1727-1767.

Kee, H. L. (2015), “Local intermediate inputs and the shared supplier spillovers of foreign direct investment,” Journal of Development Economics 112, 56-71.

Kee, H and H Tang (2016), “Domestic value added in exports: Theory and firm evidence from China” American Economic Review 106 (6): 1402-1436.

Koopman, R, Z Wang and SJ Wei (2012), “Estimating domestic content in exports when processing trade is pervasive,” Journal of Development Economics 99 (1): 178-189.

Kraemer, K, G Linden and J Dedrick (2011), “Capturing value in global networks: Apple’s iPad and iPhone,” University of California, Berkeley, Working Paper.

World Bank (2011), Harnessing regional integration for trade and growth in Southern Africa.