China’s accession to WTO reduced trade policy uncertainty, spurred structural change towards manufacturing and services, and increased economic growth

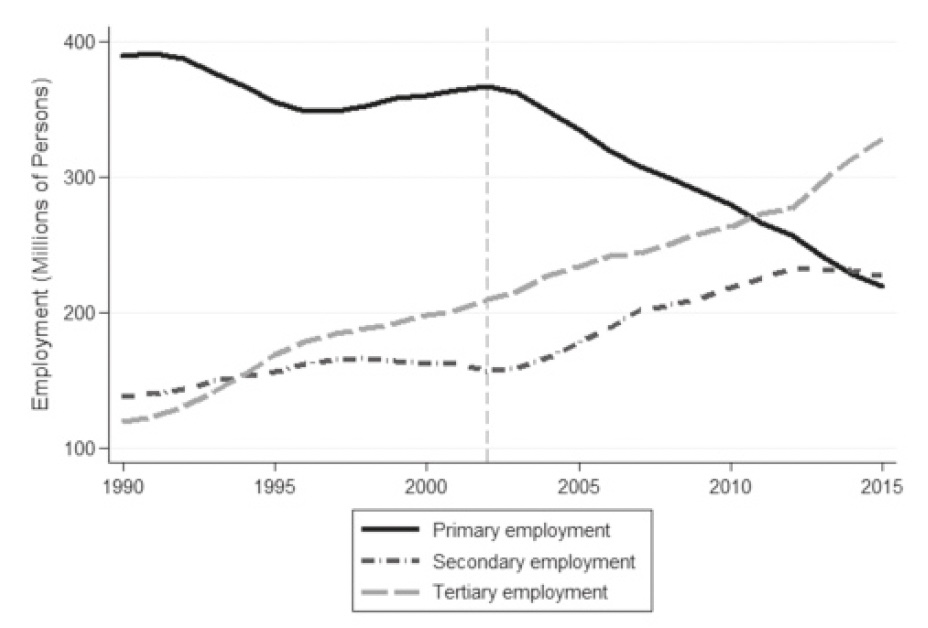

There are substantial gaps between agricultural and non-agricultural productivity in developing countries (Gollin et al. 2014). Given this pattern, structural transformation, or the systematic shift of productive factors out of agriculture, has meaningful implications for aggregate productivity and for living standards. China is a notable outlier in the developing world in the pace of structural transformation observed over the last 25 years: as Figures 1(a) and 1(b) illustrate, total employment in the agricultural sector fell from 60% of total employment in 1990 to 28% in 2015, and this sectoral shift was matched by unprecedented growth in non-agricultural output as China emerged as the factory of the world.

Figure 1 Shifts in sectoral allocations of labour and output over time

a) Composition of employment in China

b) Composition of GDP in China

Notes: The panels present aggregate statistics for China as a whole from 1990 to 2015, employing data from the National Bureau of Statistics. The primary sector includes agriculture, forestry and fishing; the secondary sector includes manufacturing and mining, and the tertiary sector includes services. GDP is reported in billions of constant 2000 yuan, and employment is reported in millions of persons.

What is the underlying cause of this rapid non-agricultural growth? While some analysts argue that trade liberalisation was an important driving factor (Sun and Heshmati 2010, McMillan et al. 2014), there is relatively little direct evidence of this relationship; Goldberg and Pavcnik (2016) indeed conclude in a recent review that there is only limited empirical evidence of the relationship between trade policy and growth in general. A complementary view argues that the key turning point was internal policy reforms, particularly those oriented around state-owned enterprises and the creation of Special Economic Zones, that enabled China to increase productivity and realise its comparative advantage in manufacturing (Song et al. 2011, Autor et al. 2016).

In our recent study (Erten and Leight 2021), we provide new evidence around the role of trade policy in China’s economic success, analysing the effects of China’s accession to the World Trade Organization on structural change and growth at the local level. We analyse a newly assembled panel of approximately 1,800 counties observed between 1996 and 2013 and focus on one specific impact of China's WTO membership: accession to the WTO significantly reduced uncertainty on US trade policy vis-à-vis China. The analysis then compares counties differentially exposed to the reduction in tariff uncertainty to identify the benefits of these export access shocks. We find that these shocks generated significant growth in exports and foreign direct investment in more-exposed regions, leading to a reallocation of labour and capital from agriculture into manufacturing and services, and significantly increasing county-level output.

China’s accession to the WTO

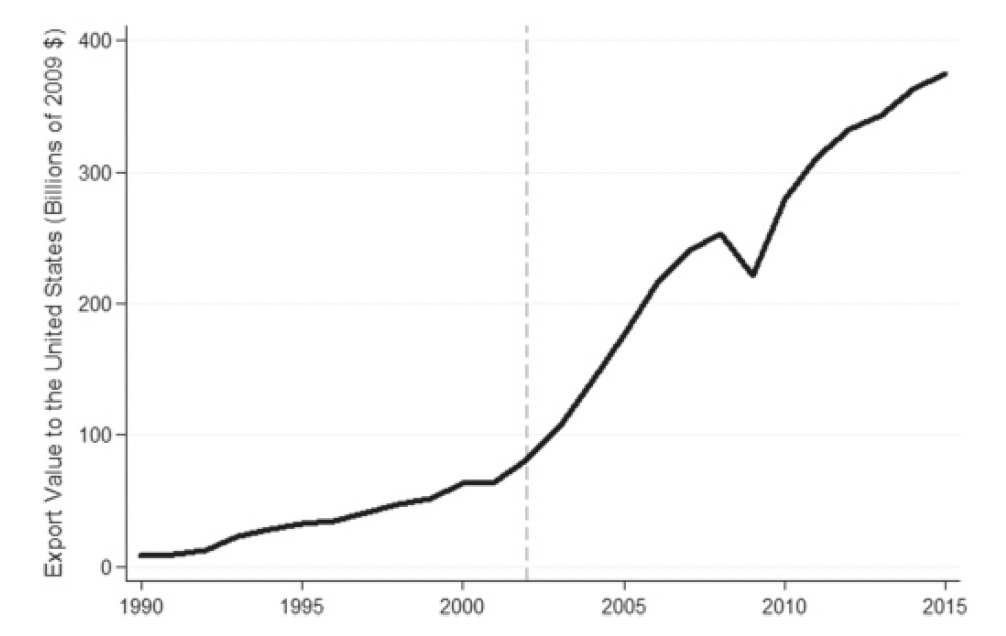

China’s accession to the WTO was the culmination of a complex and lengthy process of negotiation. Prior to accession, China’s Normal Trade Relations (NTR) status in the US market required a risky annual renewal by Congress; if the renewal had failed, Chinese exports would have been subject to the much higher rates reserved for non-market economies. For example, in 2000, the average US NTR tariff was 4%, but China would have faced an average non-NTR tariff of 31% had its status been revoked. The US permanently granted NTR status to China as of 2002, but the status of Chinese exports in other markets did not change at that point. China’s WTO membership significantly reduced uncertainty regarding US trade policy for China, generating a substantial increase in both total Chinese exports to the US and total exports altogether, as can be seen in Figures 2(a) and 2(b).

Figure 2 Dramatic increase in Chinese exports

a) China's exports to the US

b) China's total exports

Notes: The panels show exports of China to the United States and total exports of China to all countries, respectively, from 1990 to 2015. The data for China’s exports to the United States are drawn from the IMF Direction of Trade database, and the data for China’s total exports are drawn from the FRED database; both series are deflated to 2009 US dollars using the PCE price index.

Impacts of China’s WTO accession on local structural change

Our analysis utilises variation across counties in their concentration in different industries in 1990, as well as variation across industries in the gap between the lower tariffs applied to most favoured nation tariffs and the higher non-market rates. For each county, we calculate a variable denoted “NTR gap” that is equal to the weighted average of the tariff gap across local industries operating in the county; employment weights are used, constructed using each industry’s share of local employment in 1990. Intuitively, a county with a high NTR gap was exposed to a high level of uncertainty prior to WTO accession because its key industries risked high tariffs, and therefore this county benefited more from the removal of the tariff uncertainty.

The empirical strategy employed is a difference-in-differences estimation comparing counties more and less exposed to tariff uncertainty before and after WTO accession, following related literature including Pierce and Schott (2016). Additional robustness checks demonstrate no evidence of statistically significant pre-trends, and the primary results are also robust to a range of controls allowing for differential trends for counties with different characteristics at baseline.

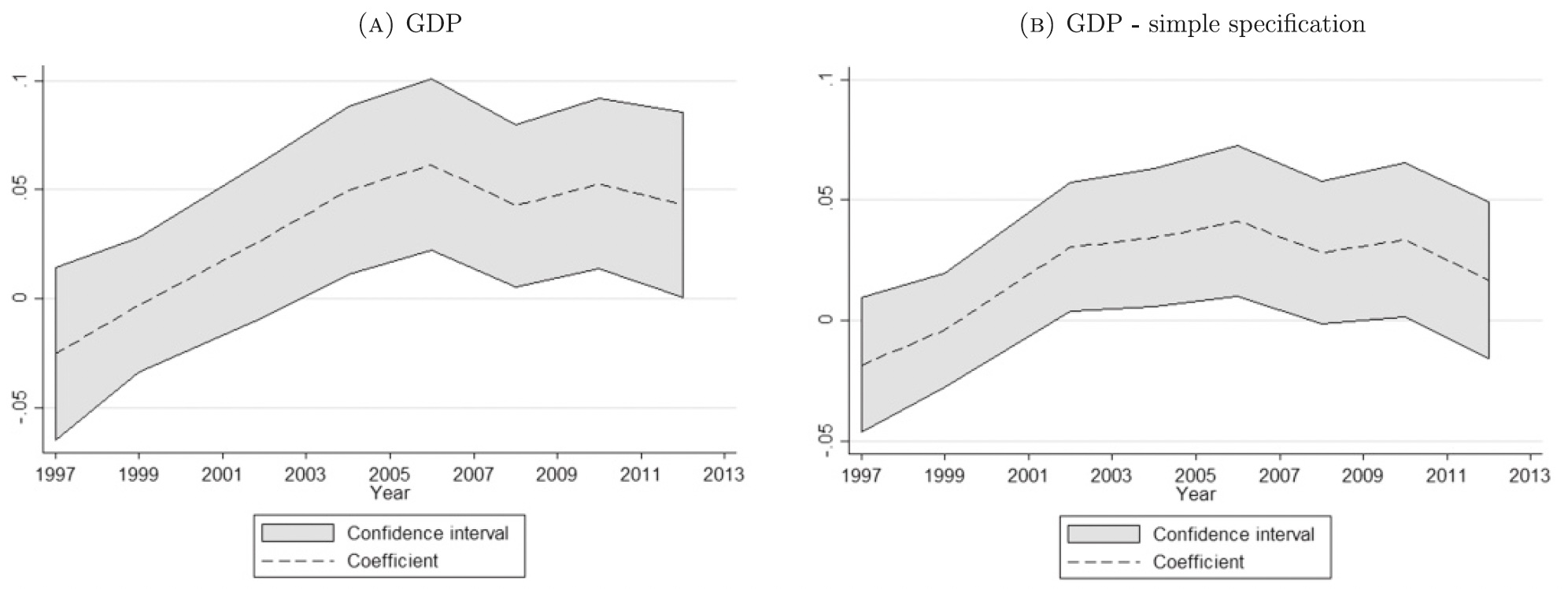

Figure 3 Increase in GDP post-WTO accession for counties exposed to tariff uncertainty ex-ante

Notes: These graphs report the coefficients on the interaction of dummy variables for each two-year interval and the county-level gap between NTR tariffs and the non-NTR rates, standardized to have mean 0 and standard deviation 1. The specifications estimated to construct panel A also include a number of control variables: an interaction of the post dummy and a dummy for high contract intensity, SOE quantile-year interactions, the industry-weighted MFA quota fill rate, the industry-weighted national tariff rate, the industry-weighted percentage of firms licensed to export, and the industry-weighted time-varying NTR rate. Province-year and county fixed effects are included, and the province-year fixed effects are interacted with an urban dummy. The specifications estimated to construct panel B include only the fixed effects of interest. Standard errors are estimated employing clustering at the county level, and the regressions are weighted with respect to baseline county-level employment.

Prior to 2002, there is little evidence of any significant difference in county-level output (GDP), comparing across counties with high and low NTR gaps. Post-2002, however, the gap emerges and becomes significant and positive, suggesting that counties that benefited more from the reduction in tariff uncertainty are growing more rapidly. Several robustness checks explore whether the results are robust to correcting for any differences in growth rates, comparing across high NTR and low NTR counties before 2002, with the positive effect of the NTR shock being persistent and significant.

When we further explore these results, we can see that counties which risked more tariff uncertainty prior to WTO accession subsequently experienced significantly faster growth in exports, greater expansion in the secondary sector, and more rapid increases in total and per capita GDP following WTO accession in 2002. The expansion of the manufacturing sector driven by export growth also affects other sectors: productive factors shift out of agriculture, agricultural production declines, tertiary output expands, and there is some evidence of in-migration. Firm-level data suggests there is an increase in value-added per worker in manufacturing, as well as an increase in wages.

Contribution of China’s WTO accession to its GDP growth

Finally, through some back-of-the-envelope calculations we quantify the contribution of the reduction in trade uncertainty to growth in China during this period. The average county in this sample shows GDP growth of 1.2 log points in the post-WTO period. Our results suggest that for a county characterised by a mean NTR gap, the reduction in tariff uncertainty in the US market to zero results in an increase in GDP of 0.1 log points. Accordingly, export-driven growth enhanced by WTO membership accounts for approximately 10% of overall GDP growth. This suggests that the contribution of reduced trade uncertainty to county-level growth is meaningful, though clearly only a part of the overall story of Chinese growth during this period.

Conclusion

In recent years, an important economic and policy debate has highlighted the evidence around the adverse effects of increasing exports from China on economic, social, and even political outcomes in the US and Europe. Our research quantifies the positive China shock as experienced by China, thereby contributing to address the evidence gap identified by Goldberg and Pavcnik (2016) on the relationship between trade, growth, and structural transformation in the developing world. By analysing the impact of the reduction in tariff uncertainty on structural transformation at the local level in China, our study joins a limited literature evaluating the role of enhanced trade access in stimulating growth in developing countries. This evidence highlights the importance of securing access to advanced country markets for developing countries that pursue export-driven growth strategies. Documenting the implications of US trade for Chinese growth also contributes to a more complete understanding of the global impact of China’s rise as a global manufacturing powerhouse over the past two decades.

References

Autor, D, D Dorn and G Hanson (2013), “The China syndrome: The impact of import competition on U.S. labor markets”, American Economic Review 103(6), 2121--2168.

Erten, B and J Leight (2021), “Exporting out of Agriculture: The impact of WTO accession on structural transformation in China”, Review of Economics and Statistics 103, 364—380.

Goldberg, P K and N Pavcnik (2016), “The Effects of Trade Policy", National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 21957.

Gollin, D, D Lagakos and M Waugh (2014), “The agricultural productivity gap", Quarterly Journal of Economics 129(2), 939--993.

McMillan, M, D Rodrik and I Verduzco-Gallo (2014), “Globalization, structural change, and productivity growth, with an update on Africa", World Development 63, 11--32.

Song, Z, K Storesletten and F Zilibotti (2011), “Growing Like China", American Economic Review 101, 196--233.

Sun, P and A Heshmati (2010), “International trade and its effects on economic growth in China", IZA Discussion Paper No. 5151.