Africa has the highest price of cement of any continent, but both its price and markup have fallen dramatically since 2011. Evidence suggests market size may explain this phenomenon.

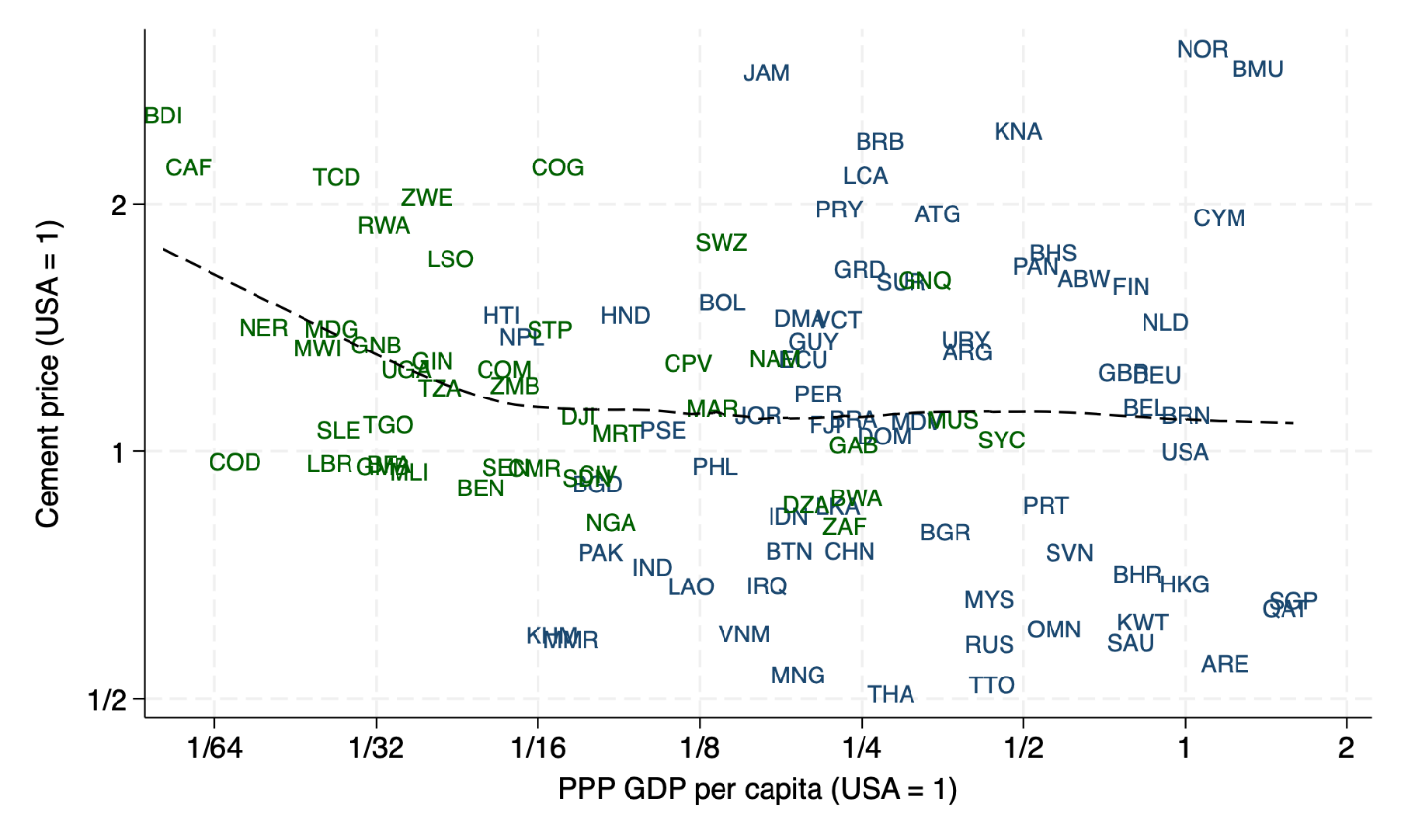

The prices of several goods, including intermediate inputs such as cement, steel reinforcement bars, urea fertiliser, and broadband internet, are higher on average in the world's poorest countries, including many in Africa (Figure 1). This is important for two reasons: higher prices for intermediate goods can slow economic growth, and this evidence runs counter to the general tendency for prices to rise with national income — a cornerstone of modern international macroeconomics.

Figure 1: Intermediate goods average prices are higher in low-income African countries.

Note: Green markers indicate countries in Africa. Source: Leone et al. AEJ Applied, forthcoming

It is not certain why we are seeing this unexpected pattern in price levels across different countries. One reason could be these higher prices reflect higher costs of production. An alternative is that higher prices might instead reflect a higher markup, as seen in markets with fewer firms and less competition.

In a forthcoming article (Leone et al. forthcoming) we distinguish between these hypotheses by looking at the case of Portland cement using an empirical industrial organisation model (see this blog for examples in other industries). According to our data, on average, 1.3% of GDP is spent on cement, making it vitally important to most economies. We find that the differences in marginal costs and markups contribute roughly to an equal share of the average difference in prices across economies.

Africa’s high price of cement

In 2011, Africa stood out as having the highest average US dollar cement price of any continent with the highest average marginal cost and the second highest average markup - at about 78%. By 2017 the average price of cement in Africa had fallen by one-third, due to a three-fifths decline in marginal cost and a two-fifths decline in markup. This brought the average price of cement in Africa much closer to other continents, challenging the view that high markups and high costs are a static feature of African economies. Our work aims to understand why cement was initially more expensive in African markets and what explains its subsequent price drop. By doing so, we draw several policy implications.

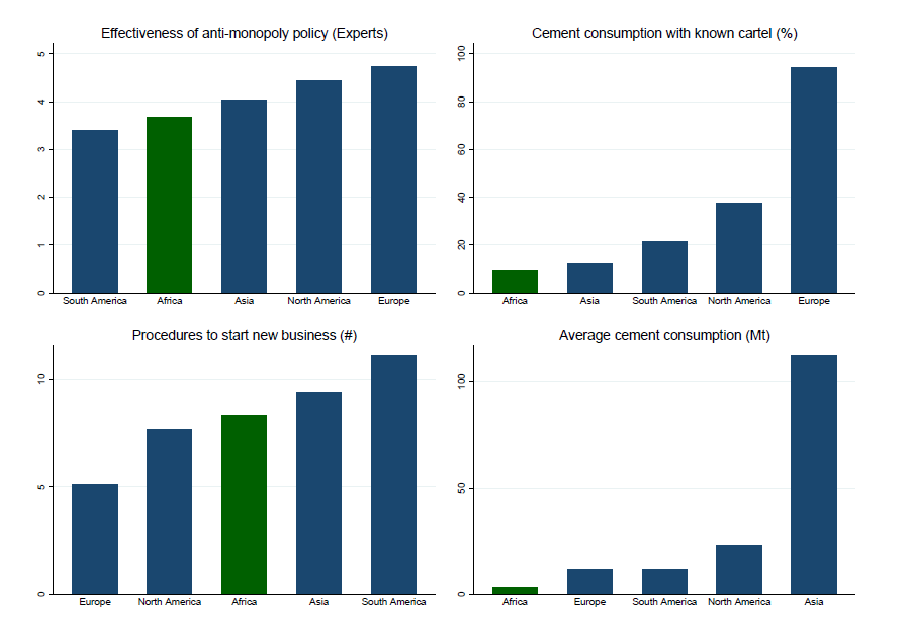

Figure 2: Several hypotheses may or may not explain high cement markups in African economies

Source: Leone et al. AEJ Applied, forthcoming

Causes of higher prices and their subsequent drop in Africa

A variety of economic forces can explain why markups on cement remain high in Africa. Figure 2 shows some initial hypotheses that we test in our research using the empirical industrial organisation toolkit. Higher markups might be explained by higher barriers to entry or by widespread cartel conduct across the continent. The upper left-hand panel of Figure 2 shows that the effectiveness of anti-monopoly policy is highest on average in Europe and North America and the second-lowest in Africa, according to a survey of experts.

A different pattern emerges in the upper right-hand panel, that shows the share of consumption sold under a known private cartel. Less than 10% of cement consumption is sold under a known cartel in the average African economy, while in Europe it is more than 90%. Taken at face value, this data suggests that Africa has less cartels than other continents. But this data is not conclusive because cartels in Africa are perhaps less known due to less effective antitrust policy, leading to fewer investigations. Our model allows us to test formally whether firms in Africa appear to be systematically colluding, potentially due to less effective antitrust policy. Given supply and demand, we estimate that prices on the continent are consistent with imperfect competition, but not joint profit maximisation by a cartel.

Can stricter entry regulations and smaller market size explain Africa’s higher markups?

The bottom left panel of Figure 2 suggests the potential role of stricter entry regulations leading to higher markups. Africa is in the middle of other continents in terms of procedures to start a new business. Africa has more procedures compared to Europe and North America, but fewer than Asia or South America. This suggests entry barriers might play a role in higher prices. Using the model, we identify fixed costs from actual firm entry decisions and find them to be economically significant and in line with figures reported in industry publications. These costs are positively related to the number of procedures to start a business, but, if anything, appear lower in Africa compared to other continents, confirming that Africa does not have extraordinarily high barriers to entry.

A final hypothesis is that higher markups in African economies reflect a small market size in many countries and so are unable to sustain more than a few competitors. The lower right-hand panel of Figure 2 shows that African markets have the lowest average cement consumption, indicating small market size. Having excluded the other hypotheses of cartel conduct, or excessive entry costs, our evidence suggests that limited demand, determined by the small average market size of many African countries, can account for high markups in prices in African markets. Consistent with this view, we observe rapid entry and a decline in marginal costs in Africa at the time of fast economic growth, explaining the price drop observed in the data.

Policy implications: Market size matters

Overall, although this evidence comes from a single industry, it offers novel insights for understanding economic development in Africa. Our findings are in contrast to theories suggesting Africa's lower-income per capita is explained by ‘oligarchies' led by major producers that use political power to erect excessive entry barriers against new entrepreneurs. Rather our results are consistent with an alternative theory in which minimum efficient scale is similar across continents and market size plays a comparatively more important role in accounting for differences in economic development.

Our findings have important policy implications. Although we do not argue against further antitrust or pro-competitive policies, our results imply that governments need to focus on increasing the size of the market to lower prices of key intermediated goods rather than only changes in regulation. If cement markups decrease the aggregate capital stock in Africa, as suggested by Beirne and Kirchberger (2023), our findings suggest that the capital stock can be most effectively increased by policies that favour market integration, rather than by deregulation of entry or cartel enforcement.

In another paper, Goldberg and Reed (2023) use similar industrial organisation methods to explore demand-side constraints on development at the level of an entire economy and show at least two ways to increase market size: international integration agreements that facilitate exports and greater income equality which raises the marginal propensity to consume from domestic income. In other industries with increasing returns to scale, achieving these policy goals could potentially encourage entry and reduce the prices of goods.

References

Goldberg, P K, and T Reed (2023), “Presidential address: Demand-side constraints in development. The role of market size, trade, and (in)equality,” Econometrica, 91(6): 1915–1950.

Kirchberger, M, and K Beirne (2023), “Concrete thinking about development,” CEPR Discussion Paper No. 18170.

Leone, F, R Macchiavello, and T Reed (forthcoming), “The high and falling price of cement in Africa,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics.