In this section, we review randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that provide causal evidence on the impacts of microcredit programmes, the extent to which microcredit functions as a tool for poverty alleviation, and whether microcredit affects different subsets of borrowers more than others. The findings from these studies provide evidence on whether microfinance is an effective development tool and offer important policy implications for designing and targeting microcredit products.

The impact of microcredit: Evidence from seven randomised evaluations

It is challenging to identify the causal impact of microcredit because of selection biases on both the demand and supply sides (Banerjee et al. 2015a). On the demand side, people who choose to borrow are likely to differ from non-borrowers, including in terms of characteristics that cannot be controlled for in empirical analyses (e.g. the quality of one’s business or idea). On the supply side, lenders may select certain regions or markets to enter and certain customers to approve, and those selection criteria are usually not transparent to researchers. These measurement challenges have provided motivation for the large number of randomised evaluations of microcredit programmes in recent years. Here we review seven RCTs that rolled out microcredit products in a variety of contexts and countries (Karlan and Zinman 2011, Angelucci et al. 2015, Attanasio et al. 2015, Augsburg et al. 2015, Banerjee et al. 2015c, Crépon et al. 2015, and Tarozzi et al. 2015). We first summarise the features of different lending programmes and randomisation methods, and then discuss their main findings.

Lender and study attributes

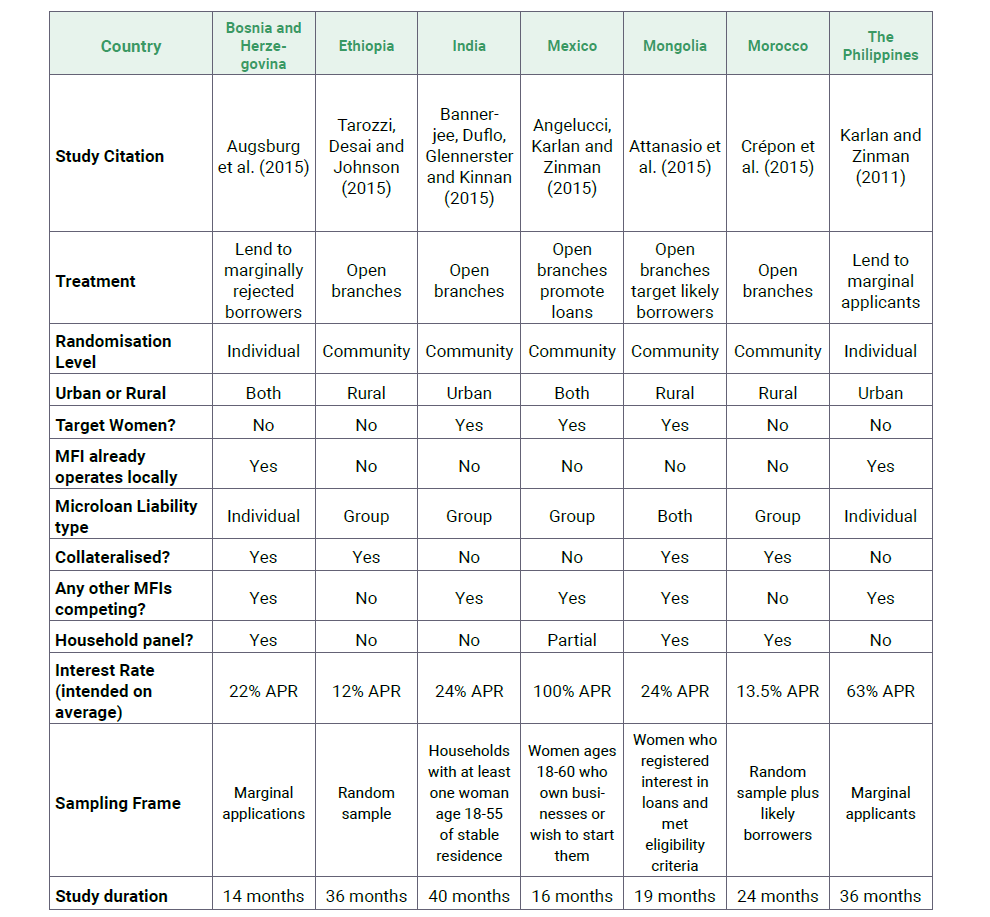

The seven studies that we consider in this section are summarised in Table 1 (extracted from Meager 2019). Those studies cover microcredit expansions in seven different countries between 2003 and 2009: Bosnia, Ethiopia, India, Mexico, Mongolia, Morocco, and the Philippines. The studies take place in both rural and urban settings. The average loan term ranges from four months (Mexico) to 16 months (Morocco), and loan interest rates were substantially lower than market interest rates in all studies except for Mexico, which offers the highest interest rate at 100% APR. The timing of follow-up surveys ranged between 14 months (Bosnia) to 40 months (India).

Table 1 Lender and study attributes by country

Source: Meager (2019)

The classic microcredit model was developed by Grameen Bank – the first formal microfinance institution (‘MFI’), with origins in rural Bangladesh. Group-based lending is one of the most prominent and novel features of the classic microcredit model, where a group self-selects its members (normally targeting women) who are then given incentives to screen and monitor each other. Repayment is incentivised not only by joint liability and peer pressure, but also by dynamic incentives where future loans are more likely to be offered to those with good repayment performance. Borrowers are often encouraged to use loans for self-employment activities (as opposed to consumption or refinancing a more expensive loan).[1] The microcredit programmes studied here have many features in common with the classic model. First, among the seven RCTs, five are joint-liability loans (Ethiopia, India, Mexico, Mongolia, and Morocco), although the Mexican study does not require group members to repay defaulting loans but encourages ‘solidarity pooling’. Second, all loan programmes offer dynamic incentives, where incentives to repay are generated by offering better terms on subsequent loans. Third, five of the seven studies encourage microenterprise investments by either labelling their loans as ‘business loans’ (Mongolia)[2], requiring business proposals (Bosnia, Ethiopia, Philippines), or requiring borrowers already to have a non-agricultural business (Morocco). Only the Indian and Mexican studies do not require or verify business activities or plans. The main divergence from the Grameen Bank model is that the Grameen model generally targets landless and asset-poor women, while only three studies here (India, Mexico, Mongolia) targeted women, and only Mongolia and Ethiopia explicitly targeted households below poverty thresholds.

A key challenge of randomised evaluations of microcredit is that it is only feasible to randomise in places where microcredit is expanding into new markets or is expanding to new borrowers in existing locations. The studies thus provide information on ‘marginal’ or ‘complier’ populations of borrowers affected by expansions and say nothing about the impact on long-time, ‘infra-marginal’ or ‘always taker’ borrowers (Banerjee et al. 2015c, Wydick 2016, Morduch 2020). The RCTs estimate the impact of expanding microcredit (which is often a relevant policy question), but they do not address whether microcredit has, in general, raised incomes or reduced poverty.

Another key challenge of randomised evaluations of microcredit programmes is the lack of statistical power because the loan take-up rates are typically low. Five of the seven evaluations (excluding India and Ethiopia) address this by restricting their sampling frames to individuals who are more likely to accept microcredit if treated. Those are individuals who had either: (i) indicated (pre-randomisation) that they have a business or are interested in starting one (as was the case in Mexico and Morocco, which had take up rates of 19% and 17%, respectively), (ii) mentioned in a survey that they are interested in borrowing (as done in Mongolia, where take-up was 50%), or (iii) those who submitted an application for a loan (as done in Bosnia and the Philippines, where take-up was close to 100%). The Indian study restricted its sample to those assessed to be ‘likely’ borrowers, mostly those who had a working-age woman in the household and had lived in the area for several years.

In terms of experimental design, the seven studies fall into two types of RCTs: those that randomised at the individual level (Bosnia and the Philippines) and those that randomised at the community level (all other studies). Randomising at the community level means that treatment status was randomly allocated to half of the neighbourhoods in the study sample, and microcredit was then offered, either via an information campaign or via a microcredit branch opening in the neighbourhood, to eligible individuals within those neighbourhoods. These individuals may or may not have actually taken a loan. The main advantage of this approach is that it captures treatment effects at the community level, which internalises any spillovers or general equilibrium effects that occur within the neighbourhood.[3] In contrast, individual level randomisation does not capture these spillovers. However, it is easier to create a sample of people who are very likely to take up credit and therefore increase statistical power. For example, the Bosnian and Filipino studies randomised treatment at the individual level and restricted their sampling frame to people who submitted applications for credit but who would previously have been on the cusp of rejection (whether due to not having sufficient collateral, a weak business proposal, or an erratic repayment history) — in other words, marginal borrowers. This strategy makes the RCT feasible, but it limits estimation to the impact on people who the lenders would have rejected for seeming too risky or unlikely to succeed. Because all individuals had indicated that they wanted a loan, take up was close to 100% for both studies. Combining the two levels of randomisation by varying the treatment intensity across communities and then randomising offers within communities could be an interesting avenue for future work.[4]

Seven insights on the impact of microcredit from the seven first-generation RCTs

The evaluation results suggest several main findings. First, although access to microcredit leads to an increase in borrowing, business creation, and investment, most studies have found that this does not translate into increases in profit, income, labour supply, and average consumption, at least over the time horizon of one to three years post-intervention. There is also no robust evidence of gains in social indicators, such as education and health. Microcredit expansion, therefore, only had modestly positive impacts on beneficiaries, with very little evidence of transformative effects[5]. This finding echoes earlier non-randomised evaluations (Morduch 1999). On the other hand, the studies also find little or no evidence of harmful effects, even under very high interest rates (as in Mexico).

Second, while the studies in these settings show that microcredit did not on average pull borrowers out of poverty in the short run, the evidence does suggest that it is a powerful tool for changing occupational choices. In Morocco, for example, there was a significant increase in self-employment income, but no net impact on total labour income or consumption. This appears to be driven by a loss in wage income, which was large enough to offset the gains in self-employment income.

There is also evidence that access to microcredit improves risk-management choices for households. In Morocco, the cheap credit enabled households to access lumpy investments such as livestock (acting as a form of self-insurance in this context) which can substitute for other risk management strategies such as income diversification through day labour. In the Philippines, there is evidence that microcredit was a preferred substitute for formal insurance as well as a complement to informal risk sharing.

Third, while many of the null results reflect a lack of statistical power, the point estimates in many cases suggest magnitudes of effects that are economically meaningful. This means that while we cannot rule out zero effects, we also cannot rule out large effects. More precision is needed, perhaps through larger sample sizes, better predictions of take-up, and meta-analysis (see the next subsection).

Fourth, the RCTs are particular to the social and cultural contexts that shape borrowing and consumption, as shown by Morvant-Roux et al. (2014) who use a qualitative study to argue that aversion to debt undermined microcredit in the Morocco study. Similarly, Cai et al. (2020) show the importance of context in an RCT of village banks in China. There, access to microcredit increased incomes by 46% and reduced poverty by 17%. They speculate that their findings are far more positive than the RCTs described above because: (a) the programmes targeted particularly poor regions, (b) the villages started with far less access to formal finance than in the RCTs described above, (c) returns to off-farm employment were high but limited by liquidity, and (d) the microcredit contracts charged low interest rates and provided borrowers substantial time to invest before having to repay.

Fifth, the underwhelming evidence of impact leads to a puzzle that has received insufficient attention: why has demand for microcredit remained strong despite the findings of these impact studies? One reason is that the impact studies reviewed here focus on impacts of “productive” uses of credit (measured by profit rates, annualised income, and annualised consumption); this focus follows the claims of microfinance pioneers like Muhammad Yunus, who based their case for microfinance on its ability to increase profit from small business and thereby to raise yearly income and yearly consumption. Borrowers, however, may take a wider view of household finance. Evidence shows that many instead use microcredit to smooth consumption and to finance large, lumpy purchases like consumer durables or home improvements (which can be hard to save for due to their scale and lumpiness). See, for example, Johnston and Morduch (2008), Kaboski and Townsend (2012), Breza and Kinnan (2021), and Lane (2024)[6]. Potential gains from microcredit might then be seen in changes in the timing and composition of spending during the year rather than annual averages.

Loeser (2022) addresses the impact/demand puzzle with estimates of microcredit interest rate elasticities in Mexico. The estimates allow Loeser to estimate consumer surplus from microcredit by evaluating how much borrowers substitute away from microcredit as interest rates rise (or increase their demand for microcredit when interest rates fall). This measure of value is based on borrowers’ willingness to pay for access to microcredit, rather than the direct measures of causal impacts estimated by RCTs. With this approach, Loeser finds that welfare gains from each unit of lending are small, but, due to the wide scale of microcredit in Mexico, the aggregate welfare gains from borrowing are large. The analysis comes with caveats (some borrowers may be trapped in debt and desperate to stay afloat, for example, so their willingness to pay for more loans does not neatly map into impact), but it offers a perspective in which consumer sovereignty and the fungibility of money are taken seriously as elements that make access to finance valuable.

Sixth, ultimately policymakers look to benefit-cost calculations when assessing potential interventions. When looking only at benefits, the RCTs deliver estimates that are small but positive, with relatively large standard errors. Those underwhelming numbers may nevertheless yield relatively favourable benefit-cost estimates. As discussed below, the median subsidies found by Cull et al. (2018) are also relatively low. As a result, Cull et al (2018, Table 7) show back-of-the envelope calculations which suggest that the benefit-cost calculus for microcredit is surprisingly positive, especially when compared to estimates for expensive anti-poverty programmes like graduation/ultra poor programmes (Banerjee et al. 2015b, Bandiera et al. 2017, Balboni et al. 2022). The calculations are only suggestive, however, given the size of standard errors on the results from the RCTs and the need for assumptions about the longevity of impacts.

Finally, in most of the seven first-generation RCTs there is limited analysis of the heterogeneity of treatment effects, in which there can be potential winners and losers of microcredit expansion. There is some suggestive evidence that the programme impact on business profit is much bigger in the right tail of the distribution (Morocco and India) and that there is significant negative impact on adolescents’ education among lower educated households (Bosnia). More rigorous analysis of heterogeneity is needed for evaluating the welfare effects of microcredit, designing policies, and targeting the right groups of beneficiaries. We discuss some recent developments in the next subsection.

The effects of microcredit can vary for different types of borrowers

Although there is little evidence of transformative effects of microcredit on the average borrower, the impact can vary across different types of borrowers. Understanding why can help policymakers target promising borrowers and improve the overall welfare impact of lending. This led to three recent papers using different methodologies to identify this heterogeneity of microcredit programmes along various dimensions.

The seven randomised evaluations reviewed in the previous section study microcredit expansions in seven countries with eight different lenders. Taking advantage of the heterogeneous social and economic contexts offered in those papers, Meager (2019) uses Bayesian hierarchical models to aggregate the evidence and estimate the heterogeneity in effects across the seven studies. The aggregate picture broadly mirrors the underwhelming effects described in the previous section, but heterogeneity is present. Interestingly, she finds that microcredit typically has null impacts on business profits if the entrepreneur does not have any previous business experience. In contrast, entrepreneurs who had started business operations before the microcredit expansion experience significantly larger treatment effects than others. However, while this effect is significant on average, it varies widely across the seven studies.

One explanation for this heterogeneity is that, since the cost of capital is high prior to the introduction of microcredit, those who select into entrepreneurship without microcredit may have business opportunities with relatively higher returns. Alternatively, it may also be driven by those businesses enjoying a ‘first mover’ advantage, or because of advantages from accumulated business experience. Another possibility is that, if microenterprise start-up costs are important, the size of standard microcredit loans might be inadequate for many clients to start new businesses – but may suffice to help clients to expand existing businesses. Directly comparing outcomes of entrepreneurs with and without prior business cannot pin down the true explanation. To more rigorously test how the impact of microcredit differs by previous business experience and mechanisms of that effect, Banerjee et al. (2019) extend the India study (Banerjee et al. 2015c) and estimate the long-run heterogeneous effects of the microcredit intervention six years after the programme. They define the pre-existing business owners as ‘gung-ho entrepreneurs’ (GEs), while the rest of the sample is a mix of consumption borrowers and ‘reluctant entrepreneurs’ (REs) who won’t start a business without the cheap credit. While the long-term programme impacts are much larger and more significant than the effects documented in the previous study, they are primarily driven by the GE sub-sample. Specifically, six years after the initial microcredit expansion, the GEs demonstrate large positive treatment effects: treated GEs have 35% more assets and generate double the amount of revenue compared with control GEs. The treatment effects for REs actually appear negative, which is driven not by negative effects on borrowers, but by the fact that microcredit led to the opening of more marginal, lower profit businesses.

The two studies discussed above suggest an important type of heterogeneous impact of microcredit programmes: although the average impact is limited, it can indeed facilitate business growth for entrepreneurs with low wealth but with some business talent (as proxied by ownership of a business when cheap credit is unavailable). Another important factor to look at is gender; many microcredit programmes focus on female entrepreneurs, and it is interesting to test whether such programmes actually generate larger impacts for women. Using a randomised experiment in Uganda, Fiala (2018) randomly offers credit and/or business training to both male and female entrepreneurs, and finds large effects on profits and sales for male-owned enterprises that were offered loans, while neither treatment has an impact on female entrepreneurs. The results thus indicate that credit-constrained men – a sample that is not targeted by traditional microcredit lenders – can benefit substantially from microcredit.[7]

More work is needed to fully explore the heterogeneous effects of microcredit programmes. For example, Meager (2019) provides suggestive evidence that the microcredit impact varies by features of loan contracts, such as interest rates and loan size. As a result, future work to identify the causal effects of household experiences and loan contract terms on microcredit impact is promising.[8] An additional dimension of heterogeneity is to what extent, and by whom, heterogeneity is predictable. We discuss this topic below in Section 4.

References

Angelucci, M, D Karlan and J Zinman (2015), “Microcredit Impacts: Evidence from a Randomized Microcredit Program Placement Experiment by Compartamos Banco”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 7(1): 151–182.

Attanasio, O, B Augsburg, R De Haas, E Fitzsimons and H Harmgart (2015), “The Impacts of Microfinance: Evidence from Joint-Liability Lending in Mongolia”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 7(1): 90–122.

Augsburg, B, R De Haas, H Harmgart and C Meghir (2015), “The Impacts of Microcredit: Evidence from Bosnia and Herzegovina”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 7(1): 183–203.

Balboni C, O Bandiera, R Burgess, M Ghatak and A Heil (2022), “Why Do People Stay Poor?”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 137(2): 785–844.

Bandiera, O, R Burgess, N Das, S Gulesci, I Rasul and M Sulaiman (2017), “Labor Markets and Poverty in Village Economies”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 132(2): 811–870.

Banerjee, A, D Karlan and J Zinman (2015a), “Six Randomized Evaluations of Microcredit: Introduction and Further Steps”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 7(1): 1–21.

Banerjee, A, E Duflo, N Goldberg, D Karlan, R Osei, W Parienté, J Shapiro, B Thuysbaert and C Udry (2015b), “A multifaceted program causes lasting progress for the very poor: Evidence from six countries”, Science 348(6236): 772–788.

Banerjee, A, E Duflo, R Glennerster and C Kinnan (2015c), “The Miracle of Microfinance? Evidence from a Randomized Evaluation”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 7(1): 22–53.

Banerjee, A, E Breza, E Duflo and C Kinnan (2019), “Can Microfinance Unlock a Poverty Trap for Some Entrepreneurs?”, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 26346.

Ben-Yishay, A, A Fraker, R Guiteras, G Palloni, N B Shah, S Shirrell and P Wang (2017), “Microcredit and willingness to pay for environmental quality: Evidence from a randomized-controlled trial of finance for sanitation in rural Cambodia”, Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 86: 121-140.

Berkouwer, S B and J T Dean (2022), “Credit, attention, and externalities in the adoption of energy efficient technologies by low-income households”, American Economic Review 112(10): 1–40.

Breza, E and C Kinnan (2021), “Measuring the Equilibrium Impacts of Credit: Evidence from the Indian Microfinance Crisis”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 136(3): 1447–1497.

Cai, S, A Park and S Wang (2020), “Microfinance Can Raise Incomes: Evidence from a Randomized Control Trial in China”, Mimeo.

Crépon, B, E Duflo, M Gurgand, R Rathelot and P Zamora (2013), “Do Labour Market Policies Have Displacement Effects? Evidence from a Clustered Randomized Experiment”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 128(2): 531-580.

Crépon, B, F Devoto, E Duflo and W Parienté (2015), “Estimating the Impact of Microcredit on Those Who Take It Up: Evidence from a Randomized Experiment in Morocco”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 7(1): 123–150.

Crépon, B, M El Komi and A Osman (2024), “Is It Who You Are or What You Get? Comparing the Impacts of Loans and Grants for Microenterprise Development”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 16(1): 286-313.

Cull, R, A Demirgüç-Kunt and J Morduch (2018), “The Microfinance Business Model: Enduring Subsidy and Modest Profit”, The World Bank Economic Review 32(2): 221–244.

Devoto, F, E Duflo, P Dupas, W Parienté and V Pons (2012), “Happiness on Tap: Piped Water Adoption in Urban Morocco”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 4(4): 68-99.

van Doornik, B, A Gomes, D Schoenherr and J Skrastins (2024a), “Savings-and-Credit Contracts”, Working Paper.

Duflo, E and E Saez (2003), “The Role of Information and Social Interactions in Retirement Plan Decisions: Evidence from a Randomized Experiment”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 118(3): 815–842.

Fiala, N (2018), “Returns to microcredit, cash grants and training for male and female microentrepreneurs in Uganda”, World Development 105: 189–200.

Johnston, D and J Morduch (2008), “The Unbanked: Evidence from Indonesia”, The World Bank Economic Review 22(3): 517–537.

Kaboski, J P and R M Townsend (2012), “The Impact of Credit on Village Economies”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 4(2): 98–133.

Karlan, D and J Zinman (2011), “Microcredit in Theory and Practice: Using Randomized Credit Scoring for Impact Evaluation”, Science 332(6035): 1278–1284.

Klapper, L F and S C Parker (2011), “Gender and the Business Environment for New Firm Creation,” The World Bank Research Observer 26: 237–257.

Lane, G (2024), “Adapting to Climate Risk with Guaranteed Credit: Evidence from Bangladesh”, Econometrica 92(2): 355–386.

Loeser, J (2022), “Consumer Surplus with Incomplete Markets: Applications to Savings and Microfinance”, Working paper.

Meager, R (2019), “Understanding the Average Impact of Microcredit Expansions: A Bayesian Hierarchical Analysis of Seven Randomized Experiments”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 11(1): 57–91.

Morvant-Roux, S, I Guérin, M Roesch and J-Y Moisseron (2014), “Adding Value to Randomization with Qualitative Analysis: The Case of Microcredit in Rural Morocco”, World Development 56: 302–312.

Morduch, J (1999), “The Microfinance Promise”, Journal of Economic Literature 37(4): 1569–1614.

Morduch, J (2020), “Why RCTs failed to answer the biggest questions about microcredit impact”, World Development 127: 104–818.

Mukherjee, S, L F Bergquist, M Burke and E Miguel (2024), “Unlocking the Benefits of Credit Through Saving”, Journal of Development Economics 171: 103346.

Tarozzi, A, A Mahajan, B Blackburn, D Kopf, L Krishnan and J Yoong (2014), “Micro-loans, Insecticide Treated Bednets, and Malaria: Evidence from a Randomized Controlled Trial in Orissa, India”, American Economic Review 104 (7): 1909-41.

Tarozzi, A, J Desai and K Johnson (2015), “The Impacts of Microcredit: Evidence from Ethiopia”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 7(1): 54–89.

Wydick, B (2016), “Microfinance on the margin: why recent impact studies may understate average treatment effects.” Journal of Development Effectiveness 8(2): 257–265.

Contact VoxDev

If you have questions, feedback, or would like more information about this article, please feel free to reach out to the VoxDev team. We’re here to help with any inquiries and to provide further insights on our research and content.