Al-Shabaab’s revenue streams and its position in the al-Qaeda network are strong predictors of its attacks and can be used to more accurately estimate the impacts of terrorism

The number of global terrorist attacks has risen drastically from less than 2,000 in the year 2000 to more than 16,000 in 2015 (Global Terrorism Database). As such, predicting terrorist incidences has risen high in the policy agenda. The Department of Homeland Security (2019), for instance, stresses the importance of detecting, preventing, and protecting against terrorist threats.

Financial flows of terrorist organisations such as fraud, kidnappings, or illegal trade are an important determinant of their activity. Accordingly, Interpol advocates gaining insights into the financing behind attacks and highlights the disruption of terrorist funding streams as an effective counter-terrorism strategy. The International Monetary Fund, in turn, argues that addressing the financing of terrorism plays a crucial role in safeguarding the stability of financial systems.

Despite its policy importance, quantitative evidence on financing and coordination between different terrorist organisations is limited. Traditionally, most studies focused on the effects of other forms of violence such as civil conflict (Miguel et al. 2004), drug related violence (Dell 2015), or homicide rates (Foureaux Koppensteiner and Menezes 2021). A topic of great interest has been to estimate the effects of violence on educational outcomes (see Verwimp et al. 2019; for an overview).

Terrorism, however, fundamentally differs in as much as terrorists use violence to cause fear and disruption in pursuit of ideological goals (Krueger and Maleckova 2003, Kydd and Walter 2006, Brandt and Sandler 2010, Santifort et al. 2013). This strategic use of violence potentially complicates any analysis of terrorism’s impact. Economic aspects of terrorism are analysed by Abadie and Gardeazabal (2003), Abadie (2006), Shapiro and Siegel (2007), Berman and Laitin (2008), Limodio (2022) and others.

Our study focuses on Kenya from 2001 to 2014 and predicts both the timing and the location of terrorist attacks using al-Shabaab’s revenue streams and position in the al-Qaeda network (Alfano and Görlach forthcoming). These predictions allow us to identify the effect of attacks on primary schooling whilst accounting for terrorists’ strategic target choices.

Predicting the timing of terrorist attacks

To predict the timing of al-Shabaab attacks, we exploit the fact that al-Shabaab derives support from the al-Qaeda network and receives direct revenues through illicit trade. We leverage three sources of time variation.

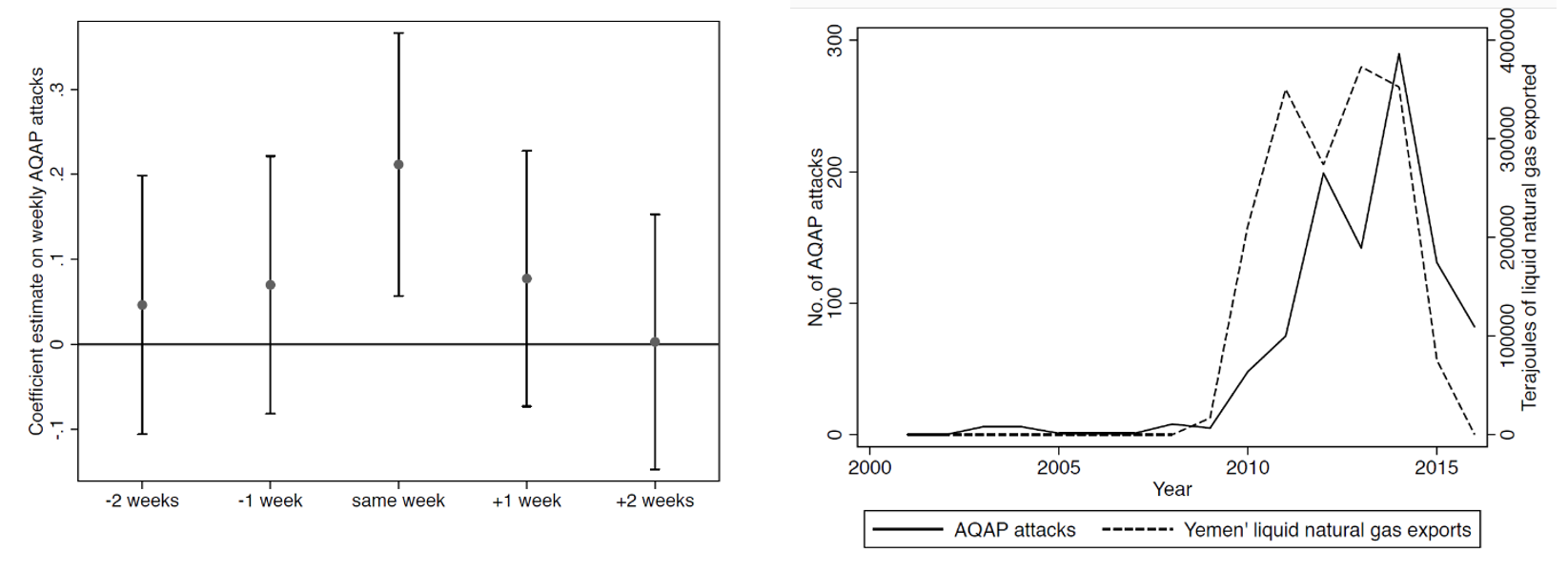

Affiliation between al-Shabaab and al-Qaeda: Al-Shabaab is part of the al-Qaeda network. Facilitated by encouragement from the al-Qaeda core, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) established close connections with al-Shabaab supporting it financially and by providing personnel and military training (Hansen 2013, Zimmermann 2013). While there are no systematic data on documented financial and material support, we regress weekly al-Shabaab attacks on AQAP activity and find a strong degree of coordination, with both organisations striking in the same week – see Figure 1a. By contrast, for the two weeks before and after we observe no relation.

Yemen’s natural gas exports: the second predictor is linked to Yemen's liquid natural gas exports, from which AQAP extracts a substantial portion of its revenue streams (Fanusie and Entz 2017a). Given that AQAP provides financial support to al-Shabaab, it is plausible that a portion of these gas revenues indirectly flow to al-Shabaab. This financial channel is crucial because terrorist organisations face challenges in saving or borrowing over time (Limodio 2022). Figure 1b plots Yemen’s liquid natural gas exports against AQAP attacks and shows a strong correlation with a one-year lag (explained by the fact that carrying out attacks takes time and organisation).

Figure 1: Al-Shabaab and al-Qaeda in Arabian Peninsula attacks and Yemen’s gas exports

a) Al-Shabaab and AQAP attacks b) AQAP attacks and Yemen’s gas exports

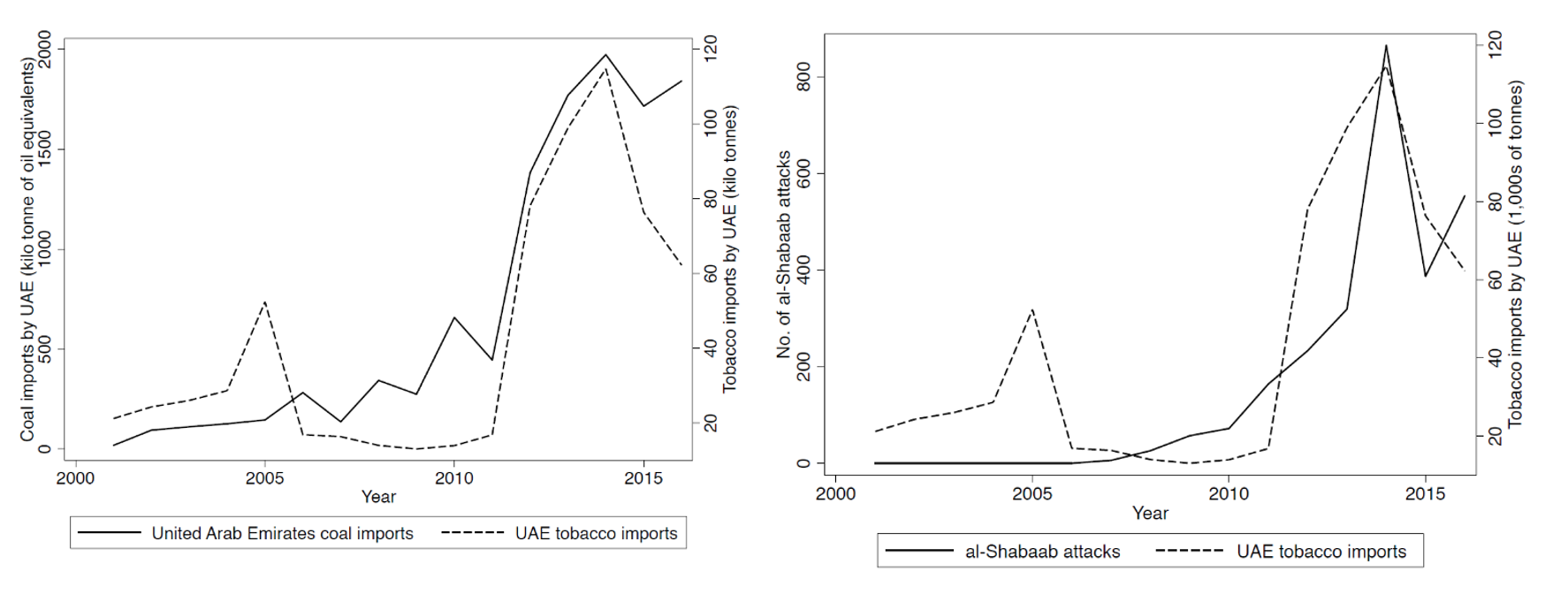

Tobacco imports into the United Arab Emirates: A major direct source for al-Shabaab’s revenues is the export of charcoal (Fanusie and Entz 2017b), predominantly to the United Arab Emirates (UAE). In fact, United Nations Security Council Resolution 2036 (2012) banned coal exports from Somalia, which, however, persist illegally (United Nations Security Council 2018). Derived from acacia trees, Somali charcoal is highly valued for its long burning quality, making it particularly well suited for water pipe smoking. Figure 2a highlights this connection showing that the UAE’s charcoal and tobacco imports track each other closely. Crucially, Figure 2b shows that UAE tobacco imports map closely to al-Shabaab activity.

Figure 2: Coal, Tobacco, and al-Shabaab attacks

a) UAE’s Coal and Tobacco imports b) Tobacco imports and al-Shabaab attacks

Predicting the location of terrorist attacks

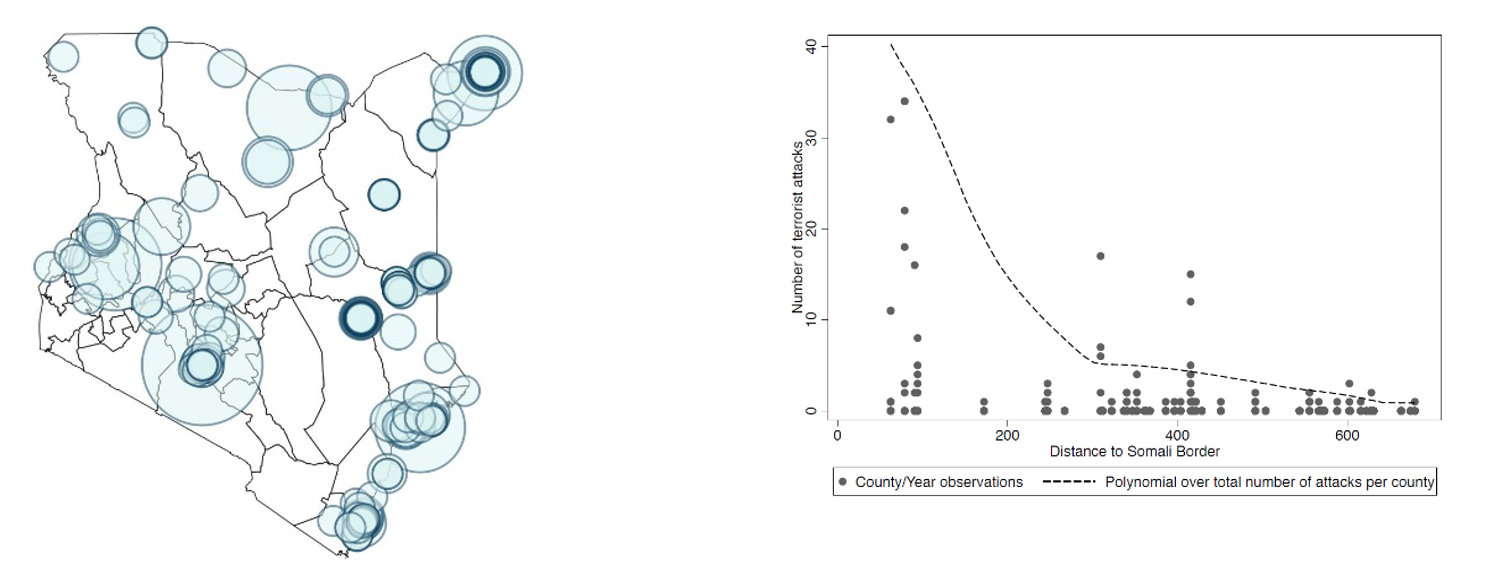

Terrorist attacks are expensive, and their cost is likely to increase with the distance from territories controlled by al-Shabaab in Somalia. Figure 3a reports the location of terrorist attacks in Kenya (2001-14) and confirms that most attacks are carried out close to the Somali border.

Figure 3: Location of terrorist attacks in Kenya 2001 to 2014

a) Map of terrorist attacks b) Distance to Somali border

To highlight this relationship further, we plot the distance between each of Kenya’s 47 counties and the Somali border against the number of terrorist attacks. Figure 3b shows that terrorist activity strongly decreases with distance from Somalia.

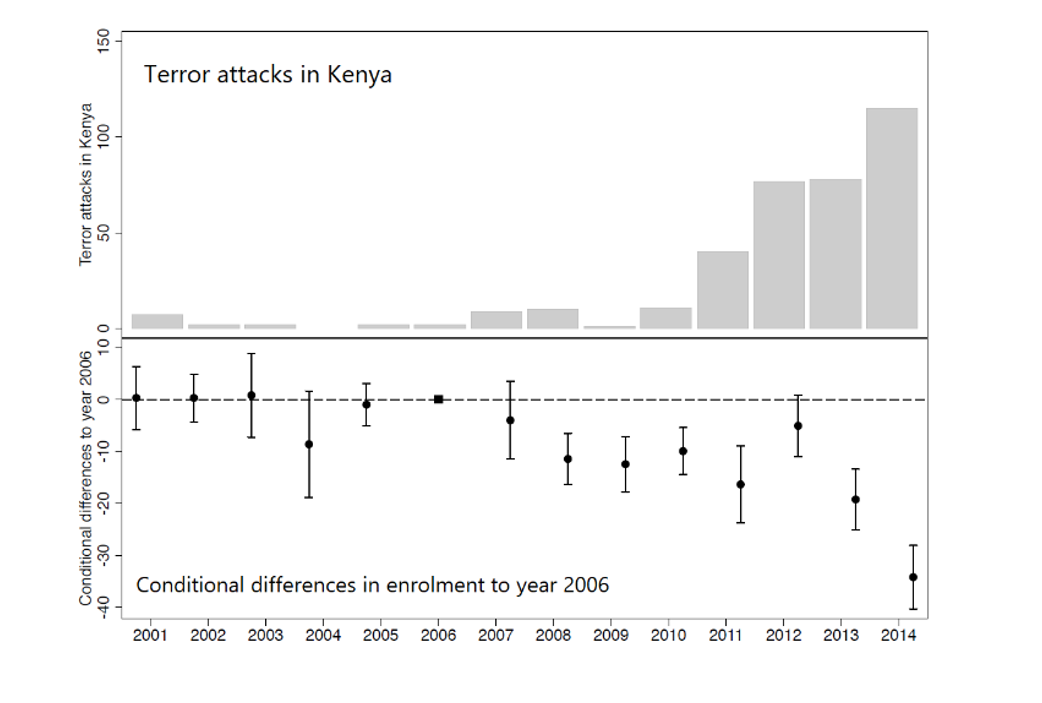

Estimating the effect of terrorist attacks on education

Whilst the effect of civil conflicts or shootings on education have been extensively explored, the role of terrorism has received relatively little attention. Analysing the effect of terrorist attacks is complicated by the fact that terrorists choose their targets strategically. To address this, we interact the three sources of time variation with distance from Somalia to predict the geo-temporal variation of terrorist attacks in Kenya, and use our predictions to estimate the effect of attacks on primary schooling. Using enrolment data for primary schools provided by the Kenyan Bureau of Statistics, we find that each attack keeps 711 children out of school. We enhance this analysis by incorporating nationally representative Demographic Health Survey (DHS) data allowing us to calculate enrolment rates dating back to the early 2000s. Figure 4 reports conditional differences in enrolment rates between areas that were affected and those that remained unaffected by terrorist attacks. Whilst we find no differences before the stark increase in terrorist activity, enrolment decreases significantly in affected areas after the onset of attacks. Our estimates suggest that each attack decreases the probability of a child entering school by the government mandated age by around 1 percentage point.

Across different datasets, the effect using our predictors is consistently larger than the one we find using actual (rather than predicted) attacks. This discrepancy suggests that al-Shabaab does not strike at random. Rather, al-Shabaab appears to target areas when they are doing particularly well. We provide evidence suggesting that the effect is driven by fears and concerns on the demand side, rather than by educational supply.

Figure 4: Terrorist attacks and school enrolment

Mapping actual and predicted attacks

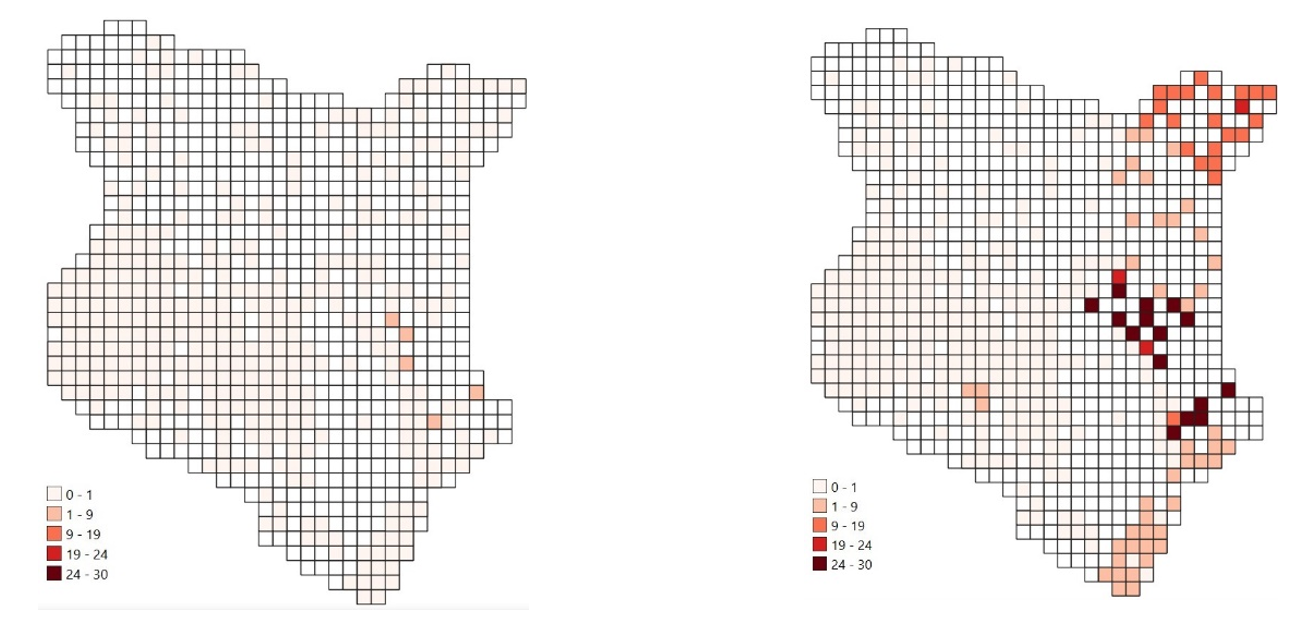

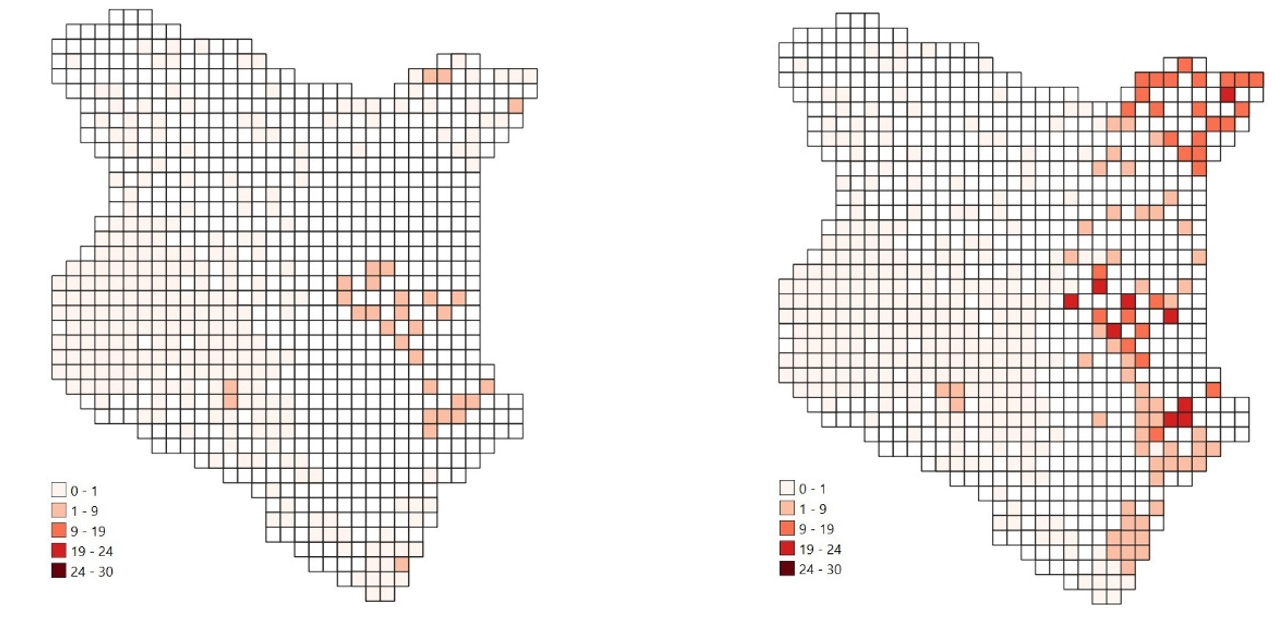

Are our predictors any good? We try to answer this question by forecasting terrorist attacks using our three predictors along with time and location effects, as well as local characteristics derived from respondents to the DHS survey. Dividing Kenya into squares of 25 km-by-25km size, figure 5 plots actual and predicted attacks for two time periods 2001 to 2010 and 2011 to 2014. Comparing panel a) to panel c) and panel b) to d), we find that the distribution of predicted attacks closely maps actual attacks carried out.

Figure 5: Predicted and actual attacks

a) Actual attacks (2001-2010) b) Actual attacks (2011-2014)

c) Predicted attacks (2001-2010) d) Predicted attacks (2011-2014)

Policy implications

The predictive power of the al-Qaeda network for al-Shabaab attacks highlights the high degree of coordination and planning that underlies violent incidences. From a policymaking point of view, our finding that terrorist attacks and revenues track each other closely suggests the interruption of terrorist funding sources as a possible counter-terrorism strategy. The negative effect of attacks on education, in turn, resonates with the fourth Global Goal of ‘provid[ing] safe, non-violent, inclusive and effective learning environments for all’ and highlights the importance of providing children with safe transportation.

References

Abadie, A (2006) “Poverty, Political Freedom, and the Roots of Terrorism,” American

Economic Review Papers& Proceedings, 96(2): 50–56.

Abadie, A and J Gardeazabal (2003), “The Economic Costs of Conflict: A Case Study of the

Basque Country,” American Economic Review, 93(1): 113–132.

Alfano, M and J-S Görlach (2024), "Terrorism and Education: Evidence from Instrumental-Variables Estimators," Journal of Applied Econometrics, forthcoming.

Berman, E and D D Laitin (2008), “Religion, terrorism and public goods: Testing the club model,” Journal of Public Economics, (92): 1942–1967.

Brandt, P T and T Sandler (2010), “What Do Transnational Terrorists Target? Has It Changed? Are We Safer?” Journal of Conflict Resolution, 54(2): 214–236.

Dell, M (2015), “Trafficking Networks and the Mexican Drug War,” American Economic Review, 105(6): 1738–79.

Department of Homeland Security (2019), “Strategic Framework for Countering Terrorism and Targetted Violence”, US Department for Homeland Security, September 2019, Washington D.C.

Fanusie, Y J and A Entz (2017), “Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula: Financial assessment,” Terror Finance Briefing Book - Center of Sanctions and Illicit Finance, 2017.

Fanusie, Y J and A Entz (2017) “Al-Shabaab: Financial assessment,” Terror Finance Briefing Book - Center of Sanctions and Illicit Finance, 2017.

Foureaux Koppensteiner, M and L Menezes (2021), “Violence and Human Capital Investments,” Journal of Labor Economics, 39(3): 787–823.

Global Terrorism Database, available at: https://www.start.umd.edu/gtd/

Hansen, S J (2013), Al-Shabaab in Somalia, Hurst and Company, London.

International Monetary Fund “Anti-Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT)” available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/Financial-Integrity/amlcft

Interpol “Tracing Terrorist Finances” available at:

https://www.interpol.int/en/Crimes/Terrorism/Tracing-terrorist-finances#:~:text=Disrupting%20the%20flow%20of%20terrorist,a%20terrorist%20attack%20is%20low.

Krueger, A B and J Maleckova (2003), “Education, Poverty and Terrorism: Is There a Causal Connection?” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17(4): 119–144.

Kydd, A H and B F Walter (2006), “The Strategies of Terrorism,” International Security, 31(1): 49–80.

Limodio, N (2022), “Terrorism Financing, Recruitment and Attacks,” Econometrica, 90(4): 1711–1742.

Miguel, E, S Satyanath, and E Sergenti (2004), “Economic Shocks and Civil Conflict: An Instrumental Variables Approach,” Journal of Political Economy, 112(4): 725 – 753.

Santifort, C, T Sandler, and P T Brandt (2013), “Terrorist attack and target diversity: Changepoints and their drivers,” Journal of Peace Research, 50(1): 75–90.

Shapiro, J and D Siegel (2007), “Underfunding in Terrorist Organizations,” International Studies Quarterly, 51: 405–429.

United Nations Security Council, “Resolution 2036, 22 February 2012,” 2012.

United Nations Security Council, “Resolution 2444, 14 November 2018,” 2018.

Verwimp, P, P Justino, and T Bruck, “The microeconomics of violent conflict,” Journal of Development Economics, 2019, 141, 102297.

Zimmermann, K (2013), “The Al Qaeda network: a new framework for defining the enemy,” Critical Threats Network report.