Ethnic politics in Africa shapes employment patterns, boosting agricultural jobs when ethnic groups gain political representation

More than half of Africa's population lives under the influence of traditional ethnic authorities (Michalopoulos and Papaioannou 2015). Contemporary economic disparities between ethnic groups are significantly tied to the strength of these ethnic institutions (Gennaioli and Rainer 2007, Michalopoulos and Papaioannou 2013). Such disparities are not merely academic concerns; they have real-world implications for development, with ethnic inequality standing out as a major factor in Africa's persistent underdevelopment (Alesina, Michalopoulos and Papaioannou 2015).

Weak state institutions further exacerbate this issue. In many parts of Africa, state control over rural areas is minimal, and traditional leaders continue to dominate land allocation and redistribution (Herbst 2000, Baldwin 2014). This dynamic fosters an environment where ethnic politics flourishes, affecting various economic outcomes. Understanding the economic consequences of ethnic politics is thus crucial for formulating effective policies.

African elections, ethnicities, and individual outcomes: A new dataset

In recent research (Amodio, Chiovelli, Hohmann 2024), we investigate the effects of ethnic politics on the labour market and examine how they impact the allocation of productive resources, particularly labour. Addressing these questions is complex as it requires detailed information on voters' location, political preferences, ethnic affiliations, electoral results, and individual labour market outcomes. To this end, we compiled a unique dataset combining two decades of geo-referenced parliamentary election data (1996-2014) with individual-level information from the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS). Our analysis leverages data across 15 countries, 32 parliamentary elections, 62 political parties, 242 ethnic groups, more than 2,000 electoral constituencies, and 400,000 individuals from 1996 to 2017. We identify links between ethnic groups and political parties in each country, exploiting the information on political affiliation and vote intention available in the Afrobarometer.

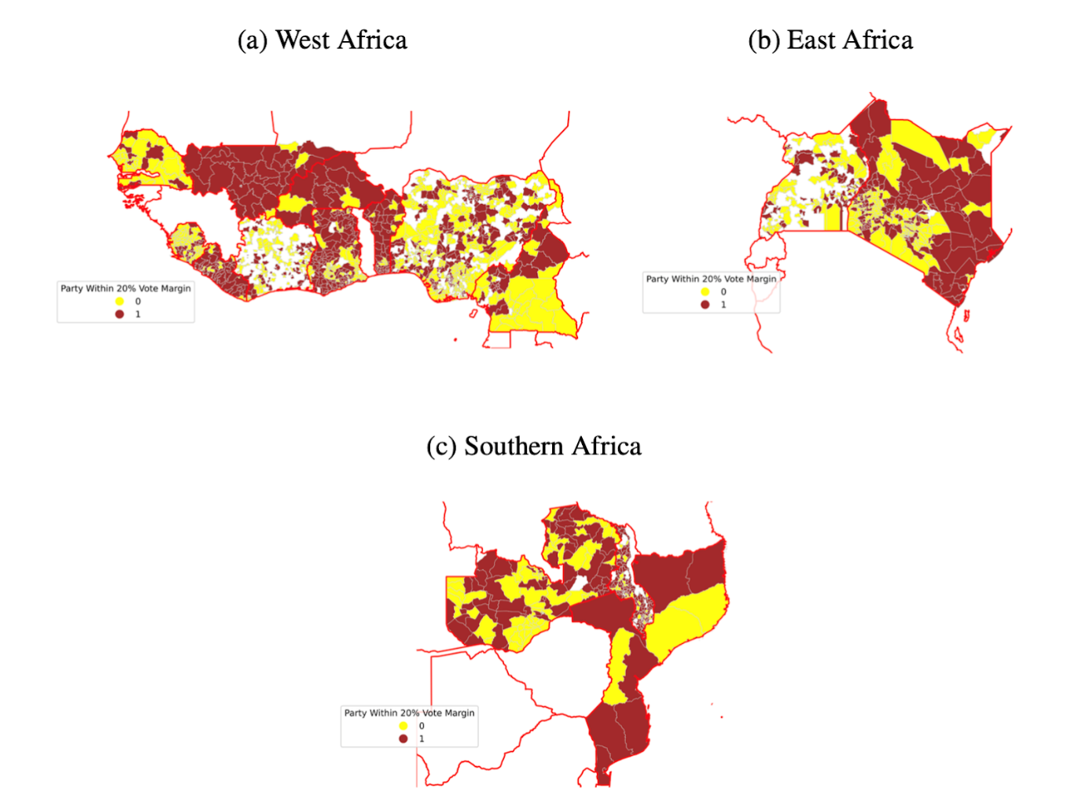

Figure 1: The coverage of our research

Notes: The figures show the spatial distribution of constituencies for West Africa (a), East Africa (b), and Southern Africa (b). We highlight in brown those constituencies in which, across all election rounds in our sample, we observe at least one party with a vote margin of less than 20% from the relevant threshold for winning a seat in parliament.

Employment and ethnic political representation

We use this data to test whether the labour market outcomes of individuals from different ethnic groups change with electoral results. To isolate the impact of ethnic politics, we compare individuals from ethnicities linked to political parties that do or do not gain a local representative in the national assembly. We focus on those groups and parties whose vote shares at the constituency level put them at the margin of gaining a regional representative in parliament. We find that individuals from ethnic groups linked to political parties that secure local parliamentary representation are significantly more likely to be employed. Specifically, these individuals are 2 to 3 percentage points more likely to be employed than those from ethnic groups whose linked parties do not gain representation. This increase translates to a 3.5 to 5.4% rise over the average employment rate near the election-winning threshold.

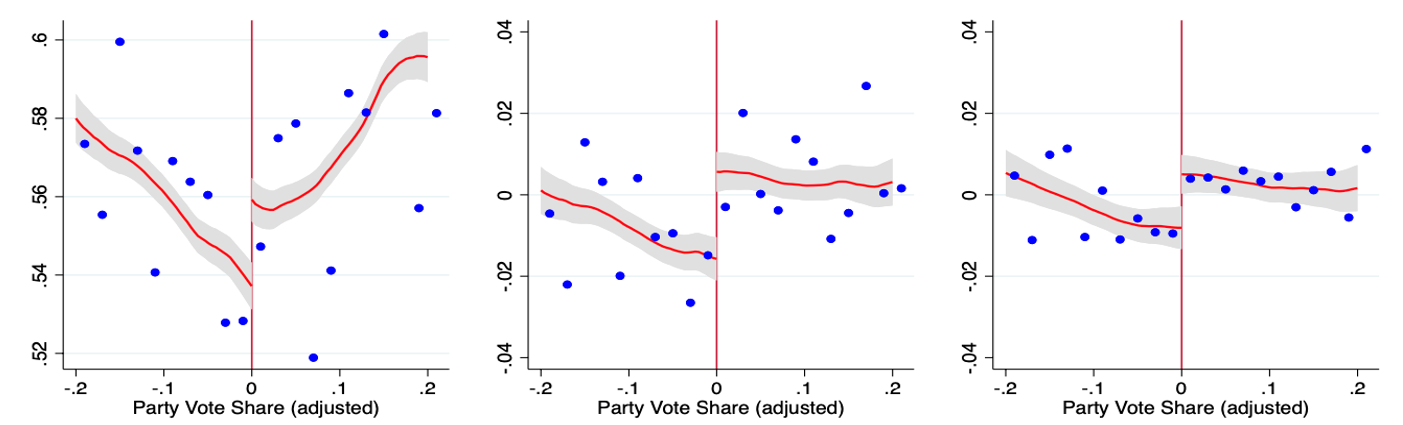

Figure 2: The relationship between electoral outcomes and individual employment probabilities

Notes: The figures provide a graphical representation of the smoothed polynomial regression fit on both sides of the threshold that determines whether the party linked to the ethnic group the individual belongs to gains a local representative in the national assembly. The first graph shows unconditional probabilities, the second shows average residual probabilities net of country-year and ethnicity fixed effects. The third also nets out constituency fixed effects.

Sectoral employment shifts

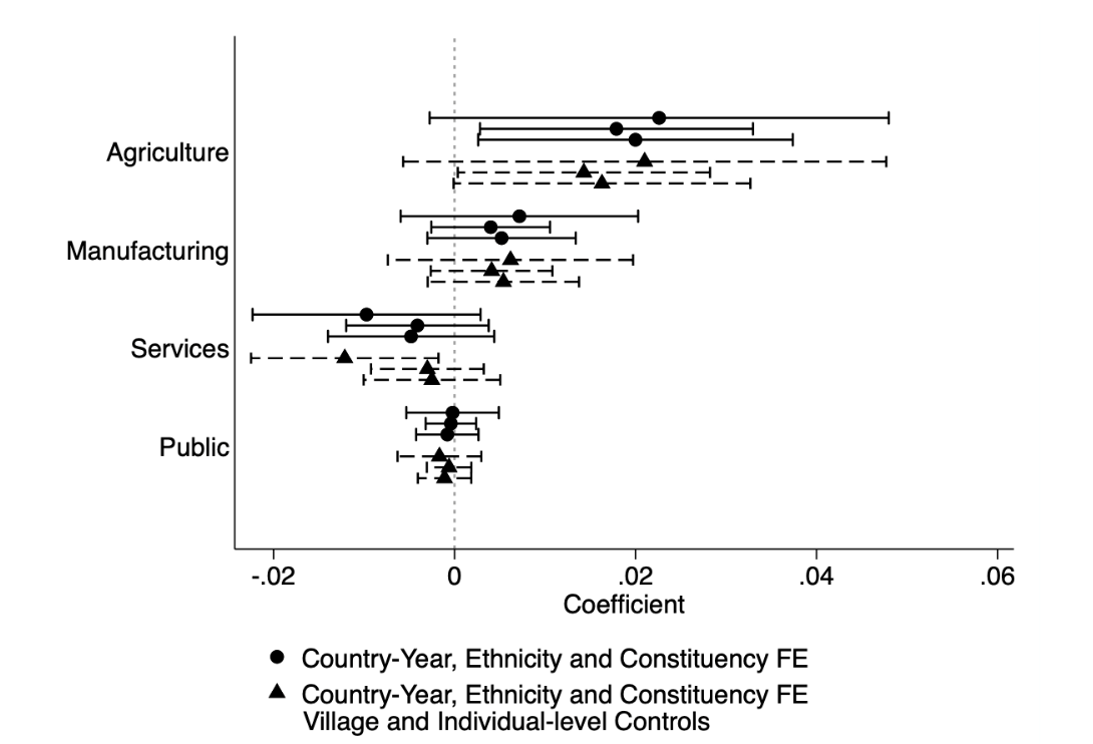

Next, we exploit the harmonised information on occupation available in the DHS to examine employment across different sectors. The employment effects of gaining a local ethnic representative are concentrated in the agricultural sector, with no significant changes observed in manufacturing, service, or public sector employment. This pattern aligns with the dual role of ethnic chiefs in African politics—as political brokers who can mobilise co-ethnics for political support and voting, and as primary authorities over land allocation (de Kadt and Larreguy 2018, Baldwin 2015).

Figure 3: Which sectors are impacted by ethnic politics in Africa?

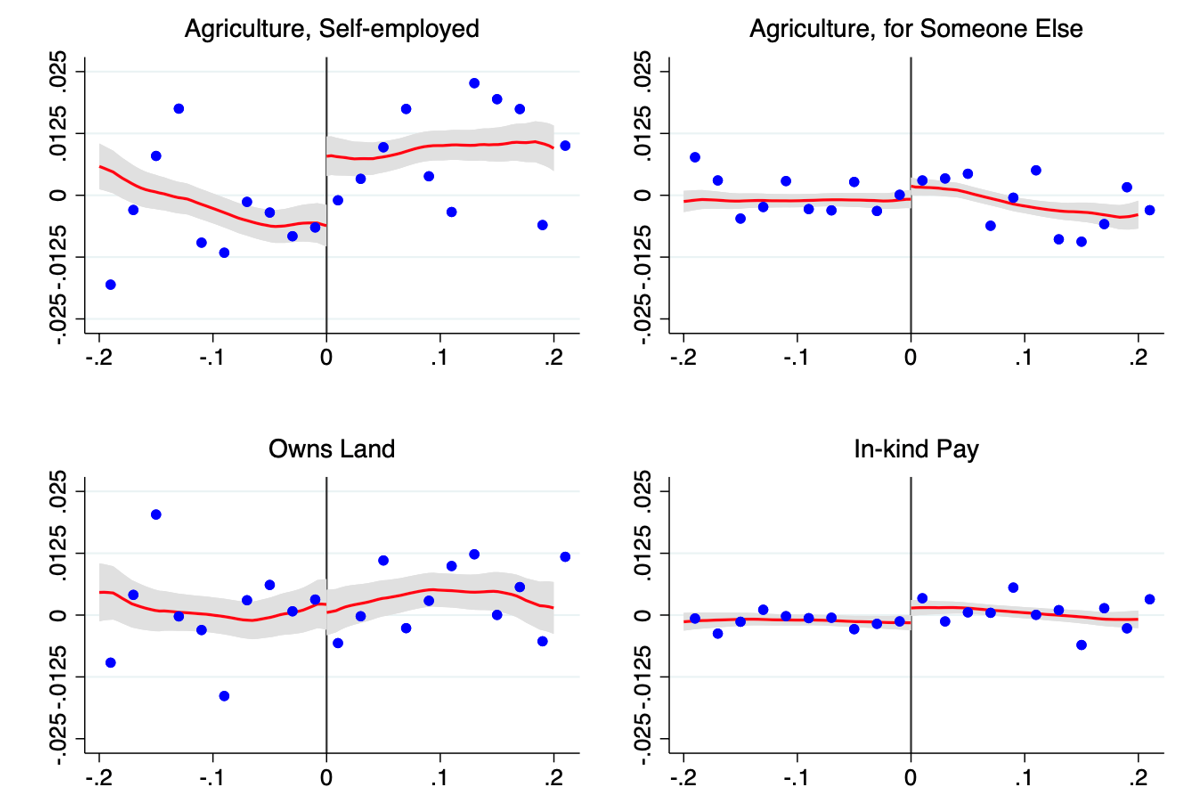

Evidence suggests that access to agricultural land is the primary mechanism behind the observed employment effects. We show that electoral outcomes significantly affect the probability of agricultural self-employment, but not the likelihood of working for someone else in agriculture. This indicates that political representation impacts individuals' ability to engage in self-directed agricultural activities. However, we do not find evidence that this increased self-employment translates into higher land ownership or receipt of in-kind compensations. These results are consistent with Africa's prevalent community-based tenure regimes, which typically lack formal land titles. At the same time, we find some evidence that individuals from ethnicities potentially disfavoured by the winning party tend to reallocate away from agriculture towards service sector employment. These findings support the hypothesis that individuals from ethnic groups linked to the winning party have improved access to agricultural land, facilitating their higher rates of agricultural self-employment.

Figure 4: The relationship between electoral outcomes and probabilities of different types of agricultural employment

Notes: The figures plot the relationship between electoral outcomes and individual probabilities of (i) self-employment in agriculture, (ii) employment in agriculture working for someone else, (iii) land ownership, and (iv) in-kind pay. The figures provide a graphical representation of the smoothed polynomial regression fit on both sides of the threshold that determines whether the party linked to the ethnic group the individual belongs to gains a local representative in the national assembly.

Policy Implications

The inability to project power from the center to the periphery and rural areas is a significant challenge for improving African state capacity. Simultaneously, there is a growing recognition of the crucial role ethnic chiefs play in the functioning of local economies in rural Africa. As democratisation progresses in several African countries and national institutions improve, it raises the question: will ethnic politics become more or less relevant?

Our findings suggest that multi-party politics can enhance the importance of ethnic ties in political and economic outcomes. The interplay between national and ethnic political structures indicates that as formal democratic processes take root, the influence of ethnic affiliations may intensify, shaping both political representation and economic opportunities. Previous literature has shown evidence of ethnic favouritism in the provision of public goods such as roads, schools, and hospitals (Franck and Rainer 2012, Burgess et al. 2015, Kramon and Posner 2016). We extend this by demonstrating that favouritism towards co-ethnics persists in African democracies and affects employment in agriculture, suggesting that access to land is a factor.

This dynamic underscores the need for policies that consider the evolving role of ethnic politics in Africa's development landscape. First, given that employment effects are primarily seen in agriculture, policies should focus on equitable land distribution and access to agricultural resources by formalising land tenure systems and ensuring transparent and inclusive land allocation processes. Second, electoral reforms that promote fair representation of all ethnic groups can help mitigate ethnic inequalities in labour markets.

Conclusion

This research sheds light on the significant role ethnic politics play in shaping labour market outcomes in Sub-Saharan Africa. By recognizing the intricate linkages between political representation, ethnic affiliations, and economic opportunities, policymakers can devise more informed and effective strategies to promote inclusive development and mitigate ethnic disparities across the continent. The findings underscore the importance of political representation in economic development. When ethnic groups gain representation in parliament, their members are more likely to be employed, especially in agriculture. This points to the crucial role of land access and agricultural policies in improving labour market outcomes for these communities. Strengthening state institutions, ensuring inclusive and fair political representation, and addressing the specific needs of different ethnic groups can help bridge the economic disparities rooted in ethnic politics. Continuous monitoring and adaptation of policies based on robust evidence will be key to achieving sustainable development and reducing ethnic inequality in Africa.

References

Alesina, A, S Michalopoulos, and E Papaioannou (2015), "Ethnic inequality", Journal of Political Economy, 123(3): 547–724.

Amodio, F, G Chiovelli, and S Hohmann (2024), "The Employment Effects of Ethnic Politics", American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 16(2): 456-91.

Baldwin, K (2014), "When Politicians Cede Control of Resources: Land, Chiefs, and Coalition-Building in Africa", Comparative Politics, 46: 253–271.

Baldwin, K (2015), The Paradox of Traditional Chiefs in Democratic Africa, Cambridge University Press.

Burgess, R, R Jedwab, E Miguel, A Morjaria, and G Padró i Miquel (2015), "The value of democracy: Evidence from road building in Kenya", American Economic Review, 105(6): 1817–51.

Calonico, S, M D Cattaneo, and R Titiunik (2014), "Robust Nonparametric Confidence Intervals for Regression Discontinuity Designs", Econometrica, 82: 2295–2326.

de Kadt, D and H A Larreguy (2018), "Agents of the regime? Traditional leaders and electoral politics in South Africa", The Journal of Politics, 80(2): 382–399.

Franck, R and I Rainer (2012), "Does the leader’s ethnicity matter? Ethnic favouritism, education, and health in Sub-Saharan Africa", American Political Science Review, 106: 294–325.

Gennaioli, N and I Rainer (2007), "The modern impact of precolonial centralization in Africa", Journal of Economic Growth, 12(3): 185–234.

Herbst, J (2000), States and power in Africa: Comparative lessons in authority and control, Princeton University Press.

Imbens, G and K Kalyanaraman (2012), "Optimal Bandwidth Choice for the Regression Discontinuity Estimator", Review of Economic Studies, 79(3): 933–959.

Kramon, E and D N Posner (2016), "Ethnic favoritism in education in Kenya", Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 11(1): 1–58.

Michalopoulos, S and E Papaioannou (2013), "Pre-colonial Ethnic Institutions and Contemporary African Development", Econometrica, 81(1): 113–152.

Michalopoulos, S and E Papaioannou (2015), "On the ethnic origins of African development: Chiefs and precolonial political centralization", The Academy of Management Perspectives, 29(1): 32–71.