Despite strict censorship, social media in China plays an important role in the spread of protests and strikes. Information spreads quickly between distant cities on Weibo, which increases the scope of collective action.

In China, protests of limited scale and scope are permitted (Cai 2008, Lorenzten 2017), but the regime is highly cautious of protests that may snowball into social movements challenging national issues and the ruling party. To understand the emergence of very large waves of protests, it is crucial to understand how events spread. In our research (Qin, Strömberg, and Wu 2024), we examine the impact of social media on the dynamics of protests and strikes, that is, how information diffusion via social media helps spread events across cities. To estimate causal effects, we leverage the rapid expansion of the information network across cities produced by the 2009 entry of Sina Weibo (Weibo for short) - the leading microblogging platform in China.

Can social media fuel protests in restricted media environments?

In fact, it is unclear whether social media has an impact on protests in a media environment that is strictly controlled, such as that of China. While social media has fuelled anti-regime protests in relatively free information environments (Tucker et al. 2016, Steinert-Threlkeld 2017, Acemoglu et al. 2018, Enikolopov et al. 2020, Fergusson and Molina 2020), this may not be the case in China. China is known to implement “the most elaborate system for internet content control in the world” (Freedom House 2013) and strategically censor social media to forestall coordinated collective action (King et al. 2013, 2014). In contrast to the settings previously studied, we find that information about logistics (e.g. where and when to meet) and organising events is scarce on Weibo due to government censorship.

Given this strict control, the first empirical question is whether information about protests and strikes circulates on Weibo. In Qin et al. (2017, 2024), we identify approximately 4 million tweets mentioning protests or strikes from 2009 to 2013. These tweets appear in bursts around the time of actual events in the real world. A large proportion of them discuss the causes of the events and criticise the government for poor policies and misconduct. Among the most retweeted posts, many express anger towards the government and sympathy for the protesters. Notably, this type of content is largely absent from traditional media in China.

How does information spread on social media in China?

To measure how information diffuses between cities on Weibo, we use retweets on topics other than protests and strikes from one city to another within the past few months. Our results show that roughly 28% of the retweets occur within one hour of the initial message being posted, while 75% happen within one day. After one hour, geographical distance plays no role in explaining who retweets a tweet. Weibo thus creates an unprecedented information network in China, instantly informing distant individuals of sensitive events.

Capturing the causal impacts of social media is challenging

We examine how this rapidly expanding social media network affects the spread of protests and strikes in a panel of Chinese cities during 2006-2017. Estimating the causal effect of social media on the dynamics of real-world events is faced with the challenge Manski (1993) called contextual and correlated effects, which are endemic to network analysis. We account for this in our analysis by measuring the correlated and contextual effects in the pre-Weibo period, which we then partial out when estimating the effect of the social media network in the post-Weibo period.

Four key main findings on the impact of social media on protest and strikes in China

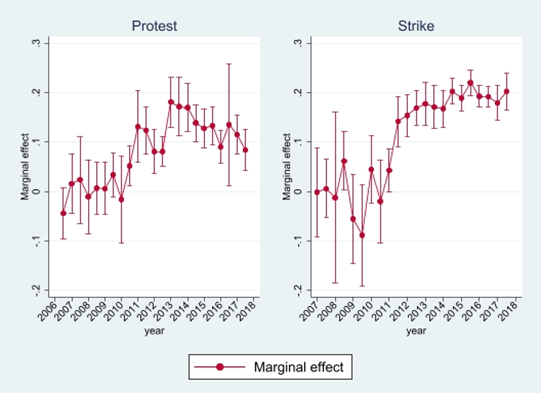

First, information diffusion on Weibo creates a strong ripple effect that swiftly spreads protests and strikes across cities. Figure 1 below illustrates how events spread across cities with strong social media ties after 2009. With the use of Weibo taking off during 2010-2011, the estimated spread of events through social media increases rapidly. After 2014 when media control became increasingly strict, the estimated spread effect for protests trends downward, whereas, for strikes, the estimated effect remains large. A likely reason is that the Chinese central government does not view the spread of strikes as regime-threatening (e.g. Kuruvilla and Zhang 2016 China Labor Bulletin 2018).

Figure 1. Spread of events through social media

Notes: The graphs plot the estimated biannual coefficients on the time-constant measure of social media connections, relative to the mean in the pre-Weibo period. The bars indicate the 95% confidence interval.

Second, information on Weibo enlarges the scope of protests and strikes. Not surprisingly, we find that the spread of events is predominantly narrow in scope, in the sense that protests spread to other protests concerning the same cause and strikes spread to other strikes within the same industry. However, Weibo also induces a significant, albeit smaller, effect on event spread across categories. Despite the relatively small spreading effect per event, the aggregate effect of cross-category spread is sizeable given the considerably larger number of events across categories than within the same category. This suggests that social media in China helps connect protesters with diverse goals, which facilitates the formation of substantial protest waves.

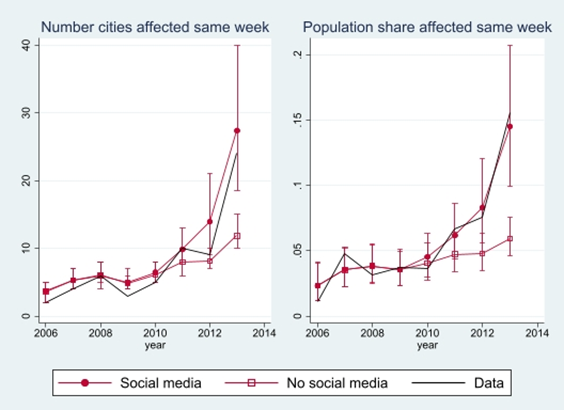

Third, Weibo increases the likelihood of very large protest waves. We measure the size of a protest wave by the number of cities experiencing protests within the same week. As shown in Figure 2, before the entry of Weibo, the largest wave of protests affected cities comprising approximately 4% of China's population—roughly the share of the two largest Chinese cities combined. Our simulation shows that without Weibo, the share of the affected population would have increased to 6% by 2013, whereas with Weibo, it would rise to nearly 15%, only slightly below the share in reality. This considerable effect is driven by the strong information connections that social media creates between China's large and distant cities. Furthermore, by amplifying the feedback from one event to another, social media substantially increases the volatility and hence the likelihood of extreme event waves. We estimate that, in 2013, there is a 5% probability of event waves affecting cities containing more than 20% of China's population.

Figure 2. Simulated event waves with and without social media

Notes: The graphs plot the number of cities (left) and share of population (right) that the largest event waves reach in the same week in simulations of the model with and without social media. The points denote the yearly average, and the bars denote the corresponding 5-95 percentile range.

Finally, we find that purging social media of content that explicitly helps organise events does not mute its effect on collective action. Existing studies have emphasised the role of social media as a platform for disseminating logistics information (e.g. where and when to meet) and organising events. However, this type of content is scarce on Weibo due to strict government censorship. Instead, most Weibo tweets about protests and strikes report what causes the event, coupled with emotional reactions. This type of content can propagate events for several reasons. First, information about an event may indicate the opening of a "window of opportunity" in which protests and strikes are allowed without substantial political risks (Zhou 1993, Weiss 2013, Truex 2019). Second, simultaneous protests across several cities can increase the likelihood of obtaining concessions or reduces the risk of punishment (e.g. Granovetter 1978, Edmond 2013, Little 2016, Barberà and Jackson 2020). Third, protesters can be motivated purely by emotions (e.g. Jasper 2008, Passarelli and Tabellini 2017), which is contagious over social media (e.g. Kramer et al. 2014).

These findings suggest that authoritarian regimes face an unavoidable trade-off in their media censorship strategy. China’s, already severe, censorship of platforms like Weibo has not succeeded in stopping the spread of protests through social media. In order to limit the spread of collective action, China would have to completely shut down public discussion about causes of social problems and silence people's emotional reactions. This extreme action would come at a direct cost to the regime, who would lose the bottom-up information that is valuable for surveillance and monitoring.

References

Acemoglu, D, T A Hassan, and A Tahoun (2018), “The Power of the Street: Evidence from Egypt's Arab Spring,” The Review of Financial Studies, 31(1): 1-42.

Barberà, S, and M O Jackson (2020), “A Model of Protests, Revolution, and Information,” Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 15(3): 297-335.

Cai, Y (2008), “Power Structure and Regime Resilience: Contentious Politics in China,” British Journal of Political Science, 38(3): 411-432.

China Labor Bulletin (2018), “The Workers' Movement in China: 2015-2017.”

Edmond, C (2013), “Information Manipulation, Coordination, and Regime Change,” Review of Economic Studies, 80(4): 1422-1458.

Enikolopov, R, M Petrova, and E Zhuravskaya (2011), “Media and Political Persuasion: Evidence from Russia,” American Economic Review, 111(7): 3253-3285.

Fergusson, L, and C Molina (2020), “Facebook Causes Protests,” Documentos de Trabajo LACEA 018004, The Latin American and Caribbean Economic Association.

Freedom House (2013), “Throttling Dissent: China’s New Leaders Refine Internet Control,” Special Report.

Granovetter, M (1978), “Threshold Models of Collective Behavior,” American Journal of Sociology, 83(6): 1420-1443.

Jasper, J M (2008), The Art of Moral Protest: Culture, Biography, and Creativity in Social Movements, University of Chicago Press.

King, G, J Pan, and M E Roberts (2013), “How Censorship in China Allows Government Criticism But Silences Collective Expression,” American Political Science Review, 107(2): 1-18.

King, G, J Pan, and M E Roberts (2014), “Reverse-Engineering Censorship in China: Randomized Experimentation and Participant Observation,” Science, 345(6199): 1-10.

Kramer, A D, J E Guillory, and J T Hancock (2014), “Experimental Evidence of Massive-Scale Emotional Contagion through Social Networks,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(24): 8788-8790.

Kuruvilla, S, and H Zhang (2016), “Labor Unrest and Incipient Collective Bargaining in China,” Management and Organization Review, 12(1): 159-187.

Little, A T (2016), “Communication Technology and Protest,” The Journal of Politics, 78(1): 152-166.

Lorentzen, P (2017), “Designing Contentious Politics in Post-1989 China,” Modern China, 43(5): 459-493.

Manski, C (1993), “Identification of Endogenous Social Effects: The Reflection Problem,” Review of Economic Studies, 60(3): 531-542.

Passarelli, F, and G Tabellini (2017), “Emotions and Political Unrest,” Journal of Political Economy, 125(3): 903-946.

Qin, B, D Strömberg, and Y Wu (2017), “Why Does China Allow Freer Social Media? Protests versus Surveillance and Propaganda,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(1): 117-140.

Qin, B, D Strömberg, and Y Wu (2024), “Social Media and Collective Action in China,” accepted at Econometrica. Available at https://www.yanhuiwu.com/documents/social_media_collective_action_China.pdf

Steinert-Threlkeld, Z C (2017), “Spontaneous Collective Action: Peripheral Mobilization during the Arab Spring,” American Political Science Review, 111(2): 379-403.

Truex, R (2019), “Focal Points, Dissident Calendars, and Preemptive Repression,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, 63(4): 1032-1052.

Tucker, J A, J Nagler, M MacDuffee, P B Metzger, D Penfold-Brown, and R Bonneau (2016), “Big Data, Social Media, and Protest,” In: R M Alvarez (ed.), Computational Social Science: Discovery and Prediction, Analytical Methods for Social Research, Cambridge University Press, 199-224.

Weiss, J C (2013), “Authoritarian Signaling, Mass Audiences, and Nationalist Protest in China,” International Organization, 67: 1-35.

Zhou, X (1993), “Unorganized Interests and Collective Action in Communist China,” American Sociological Review, 58(1): 54-73