Social media provides a powerful mechanism for citizens to make their voices heard, which spurs improvements in how governments regulate pollution

Public engagement is often seen as a way to improve the implementation of public policies. When the public monitors the performance of governments and advocates for policy outcomes, officials and government agencies may have new incentives and information to meet public demands (Björkman and Svensson 2009, Anderson et al. 2019), though the evidence is mixed (Banerjee et al. 2010, Buntaine et al. 2021). Public participation is especially relevant to the management of pollution. When high levels of pollution filled the air and waterways of American communities in the 1960s, citizens took to the streets and marched for change on the first Earth Day in 1970—leading to major government efforts to control pollution. Since then, governments around the world have disclosed more information about pollution to the public and opened channels for the public to make their voices heard.

Nowadays, social media has become a gathering place for people throughout the world. Across a range of policy issues, people use it to organise and advocate for policy outcomes (Enikolopov et al. 2020). But does it serve as an effective platform for citizens to communicate their preferences? Are governments responsive to public demands expressed on social media? We explore these questions in a large-scale randomised trial of complaints about violations of pollution standards in China (Buntaine et al. 2022).

Public engagement in environmental governance in China

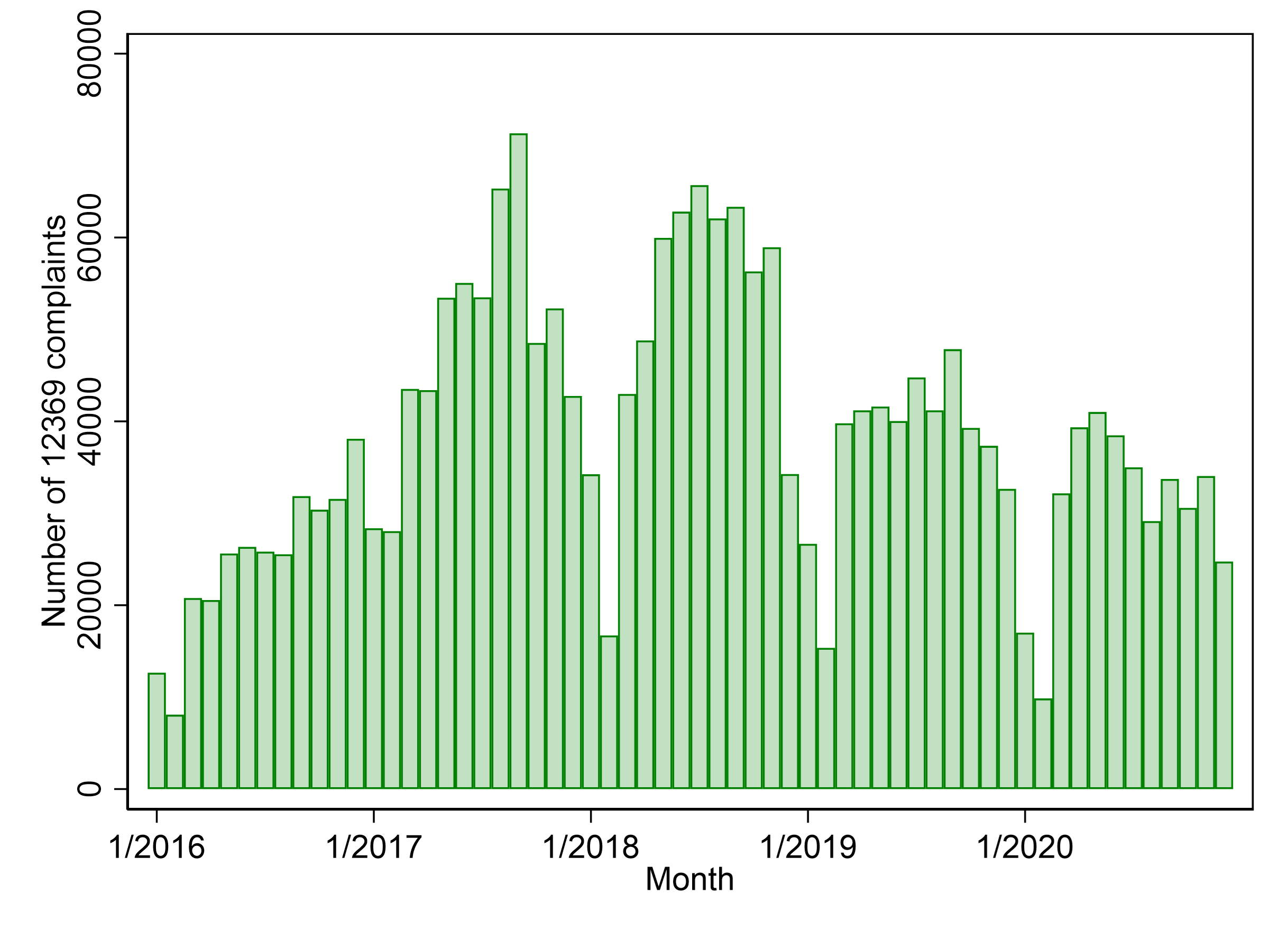

In the last two decades, China has launched a ‘war on pollution’ to address the severe impacts rapid industrialisation has had on the environment and human health (Greenstone et al. 2021). As part of these efforts, government units have created official channels that citizens can use to complain about facilities or ambient environmental conditions to local governments. The channels include hotlines, webforms, and social media accounts of government departments. In the last several years, many complaints have been filed through these channels (Figure 1). The growing rate of public engagement raises important questions: Which types of complaints cause responsiveness from local government agencies who manage pollution? Does responsiveness to complaints about some firms crowd out enforcement effort from others?

Figure 1. Monthly complaints received through China’s 12,369 environmental monitoring hotlines.

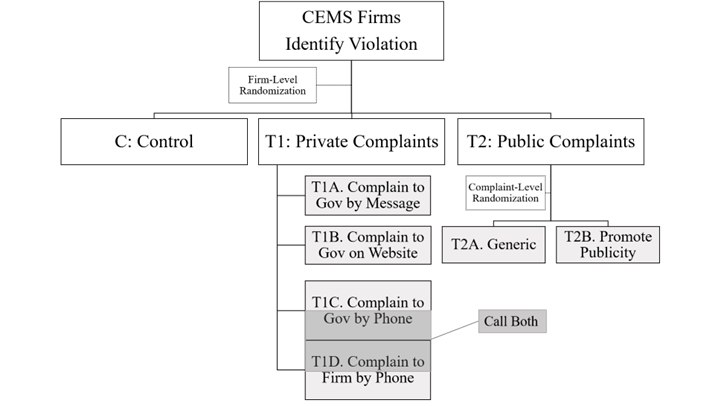

To investigate these questions, we worked with a team of volunteers to monitor the emissions of more than 25,000 industrial firms in China daily, and file complaints the next day whenever a facility exceeded permitted limits. This process generated more than 3,000 complaints over eight months. We assigned each firm to a type of complaint when they violated emissions standards, or to a control condition where violations did not generate a complaint (Figure 2). The two main types of treatment assignments were public complaints made by social media and observable by anyone online, or private complaints made through a government hotline or website and not observable to anyone except the complainant and the receiving department. We also assigned different intensities of complaints at the prefectural city level to investigate whether complaints actually increase overall enforcement, as opposed to just shifting enforcement between firms.

Figure 2. Research design showing the randomised treatment arms.

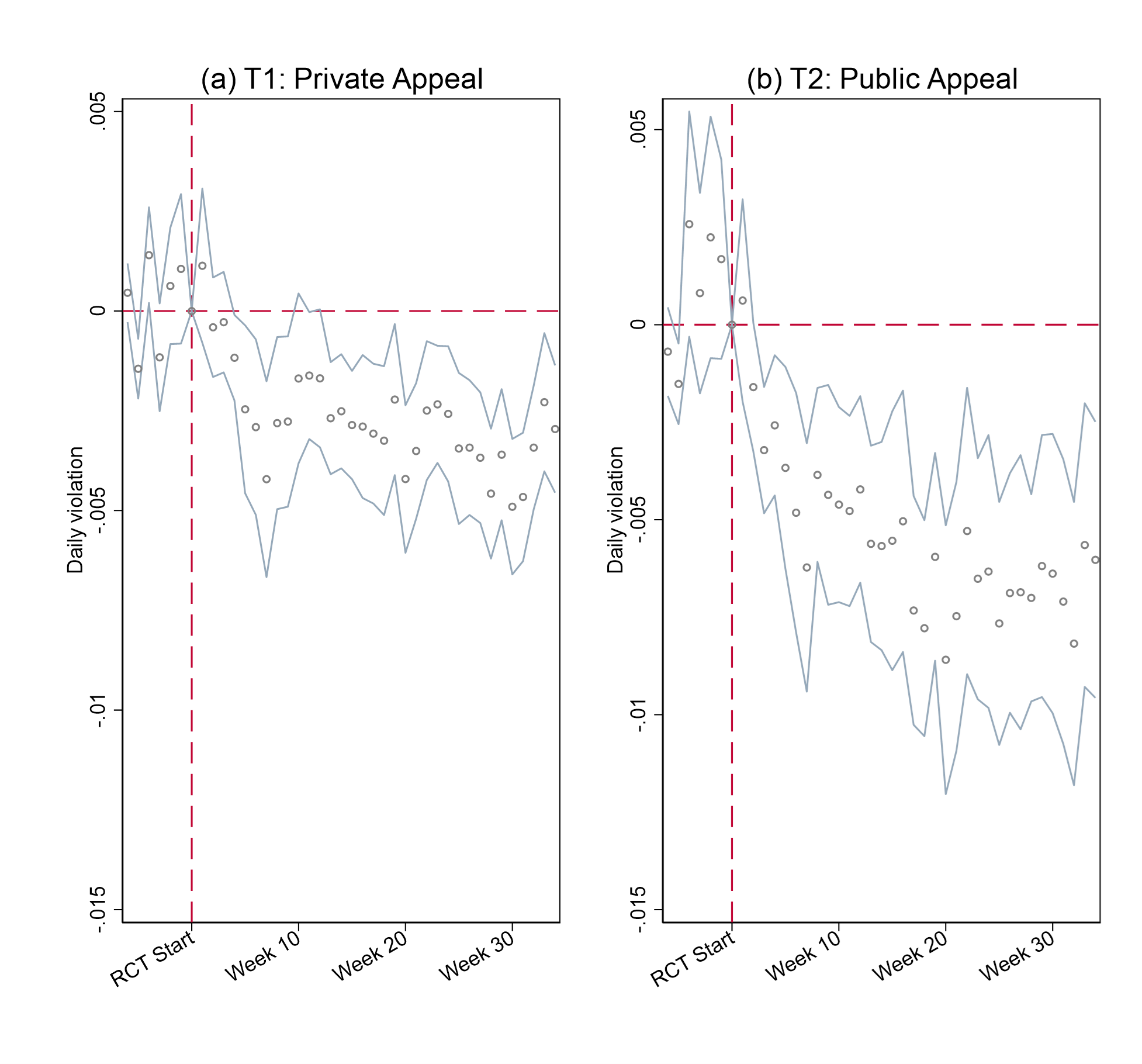

Public complaints generate more pollution reductions than private complaints

The main result of the experiment is that public complaints generate more of a reduction in violations and emissions concentrations by firms than similar complaints made through private channels (Figure 3). Firms assigned to public complaints decreased violations by more than 60%, and decreased air and water pollution by 12.2% and 3.7% respectively. Private complaints also led to improvements, but by a lesser amount. When the visibility of the social media appeals was increased by experimentally adding ‘likes’ and ‘shares’, creating at least the appearance of growing public support, government regulators were 40% more likely to reply and 65% more likely to inspect the polluting plants mentioned in the complaint. Taken together, these results demonstrate that increasing the visibility of the complaint, and potentially, public attention to the response by government, provides new incentives for local governments to regulate stringently. Social media provides a powerful mechanism for citizens to make their voices heard.

Figure 3. Changes in the daily rate of violations by treatment arm.

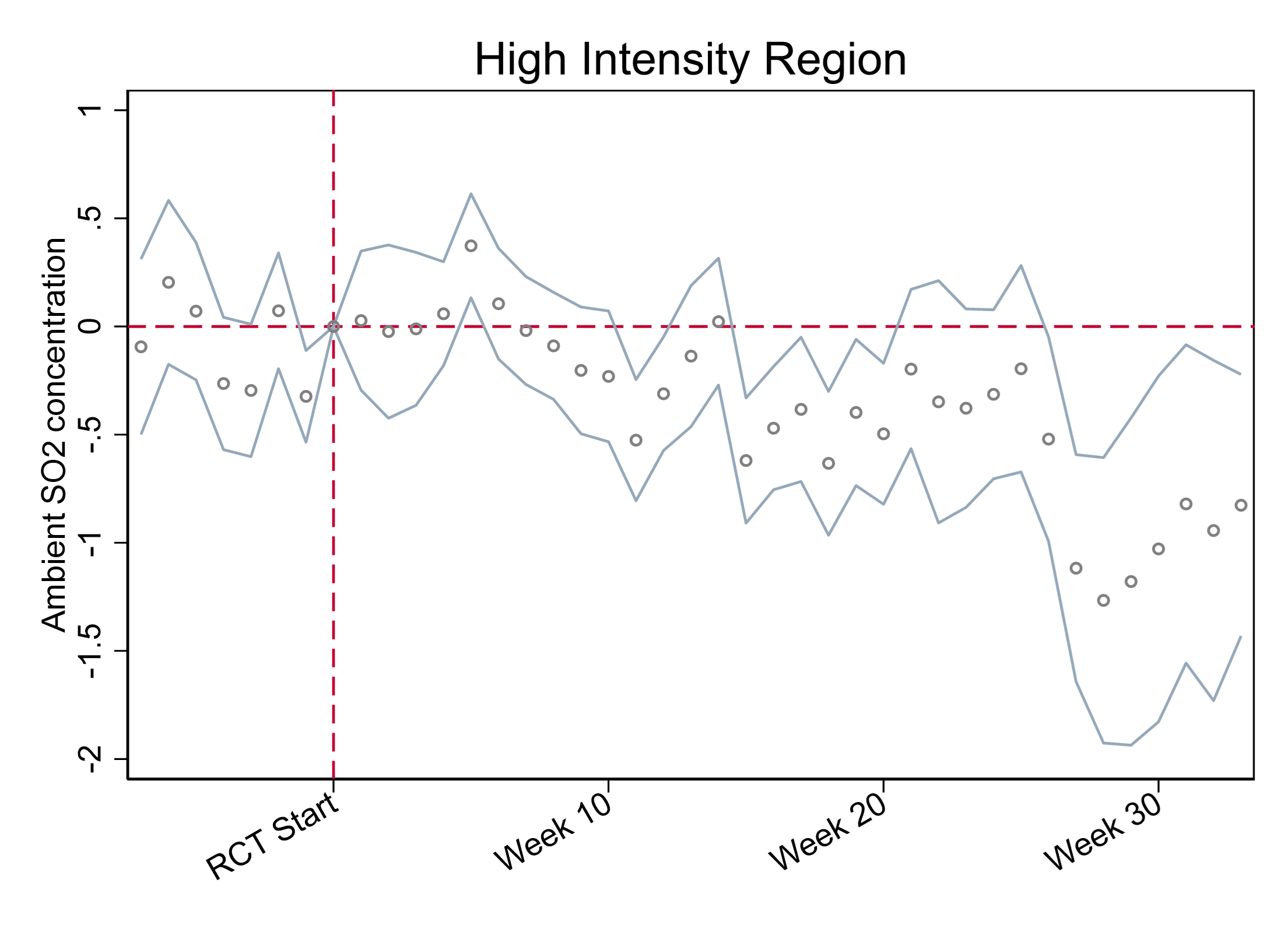

Complaints do not just shift enforcement efforts

We also investigated the indirect impacts of citizen participation. One concern about regulating firms using complaints against them is that this could simply shift enforcement from firms with less public scrutiny to firms with more public scrutiny, resulting in no net reductions in violations or pollution. These kinds of general equilibrium effects are crucial to understanding the overall implications of public participation, but are difficult to study at scale. Because we assigned different proportions of firms to complaint treatments within cities, we can assess the net effects of more complaints about violations. We found that increasing the number of citizen complaints results in lower levels of ambient pollution. This implies that citizen participation does not just shift enforcement, but rather results in better outcomes overall.

Figure 4. Effects of city-level treatment intensity on ambient SO2 concentrations.

Implications

Our study found that social media can be a very effective and easy tool to involve citizens in the government process and hold regulators accountable. Social media is the new ‘public street’, galvanising momentum for change in much the same way as a protest or march. The more popular the social media posts are, the more effective they are in generating action from the government. The fact that the more popular posts spurred more action from government officials confirms that there is a lot of opportunity for citizens to participate in governance and help improve government accountability. Our study demonstrates that providing the public with information about individual polluter’s emissions can lead to pollution reduction. This has long been hypothesised by proponents of the United States’ Toxics Release Inventory programme and other similar programmes elsewhere in the world (Konar and Cohen 1997, Bui and Mayer 2003).

Previously, this type of bottom-up citizen participation has mostly been investigated in other parts of the world, and especially in contexts where leaders are voted into power, as they are expected to feel more accountable to those electing them. Our study provides the first experimental evidence that this type of citizen engagement can also be very effective in a context like China, showing that local governments feel accountable to public opinion, especially when it is expressed online and is visible to everyone. It indicates that social media offers an effective way for citizens to engage with governments and make their voices heard. More than just making their voices heard, it changes the way that governments regulate pollution.

References

Anderson, S E, M T Buntaine, M Liu and B Zhang (2019), “Non‐governmental monitoring of local governments increases compliance with central mandates: a national‐scale field experiment in China”, American Journal of Political Science 63(3): 626-643.

Banerjee, A V, R Banerji, E Duflo, R Glennerster, and S Khemani (2010), “Pitfalls of participatory programs: Evidence from a randomized evaluation in education in India”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 2(1): 1-30.

Björkman, M and J Svensson (2009), “Power to the people: evidence from a randomized field experiment on community-based monitoring in Uganda”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 124(2): 735-769.

Bui, L T and C J Mayer (2003), “Regulation and capitalization of environmental amenities: evidence from the toxic release inventory in Massachusetts”, Review of Economics and statistics 85(3): 693-708.

Buntaine, M T, P Hunnicutt, and P Komakech (2021), “The challenges of using citizen reporting to improve public services: A field experiment on solid waste services in Uganda”, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 31(1): 108-127.

Buntaine, M, M Greenstone, G He, M Liu, S Wang, and B Zhang (2022), “Does the Squeaky Wheel Get More Grease? The Direct and Indirect Effects of Citizen Participation on Environmental Governance in China”, NBER Working Paper 30539.

Enikolopov, R, A Makarin, and M Petrova (2020), “Social media and protest participation: Evidence from Russia”, Econometrica 88(4): 1479-1514.

Greenstone, M, G He, S Li, and E Y Zou (2021), “China’s war on pollution: Evidence from the first 5 years”, Review of Environmental Economics and Policy 15(2): 281-299.

Konar, S and M A Cohen (1997), “Information as regulation: The effect of community right to know laws on toxic emissions”, Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 32(1): 109-124.