Political manipulation in India's electricity sector, involving illicit subsidies to constituents of the ruling party, results in staggering efficiency losses.

Public utilities in many developing countries, including India, are vulnerable to political manipulation. Politicians, especially from ruling parties, often misuse their influence over state-controlled electricity providers to benefit their own constituencies. These practices can create inefficiencies and worsen economic inequality (Min and Golden 2014).

In recent research (Mahadevan 2024), I find that political favouritism in India's electricity sector leads to underreporting of electricity consumption in favoured constituencies, exacerbating inefficiency in the power sector. My study uses a combination of administrative billing data and satellite nighttime luminosity data to uncover the illicit electricity subsidies conferred to constituencies where the ruling party narrowly won elections.

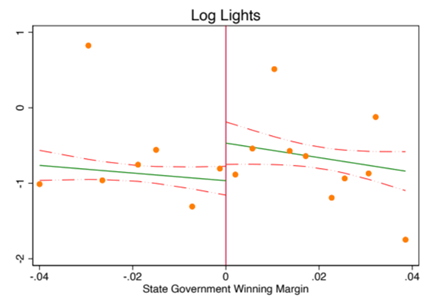

Constituencies aligned with the ruling party consume more electricity according to satellite data

Using a regression discontinuity design (RDD), I find that actual electricity consumption - measured by a satellite - was significantly and discontinuously higher for constituencies narrowly aligned with the state ruling party in the state of West Bengal, India (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Overconsumption of electricity consumption

Notes: All figures sourced from Mahadeven 2024.

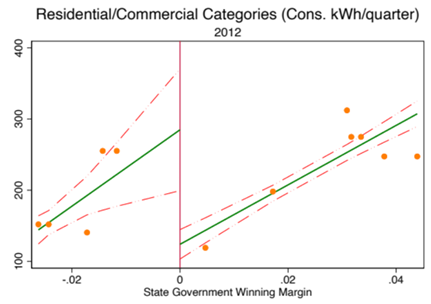

However, the administrative data tells a different story: Ruling party constituents are billed for less consumption

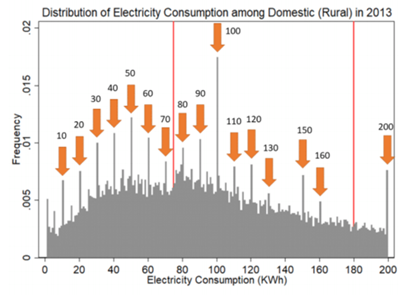

When examining administrative data from the large public electricity utility in West Bengal, I find that constituencies aligned with the ruling party appear to consume less electricity than their unaligned counterparts (Figure 2 left panel). An analysis of the billed consumption distribution across constituencies reveals systematic anomalies in the data, with frequent instances of consumption being reported in neat multiples of ten (Figure 3 right panel). Using an RDD, the probability of billed consumption being reported as a multiple of ten is significantly higher in constituencies of the ruling party. The use of Benford’s Law, a tool for detecting data fraud, confirms that billing data in constituencies aligned with the ruling party deviates significantly from expected distributions. The data anomalies appear soon after an election, when the ruling party has taken over governance.

Figure 2: Underreporting of electricity consumption (left panel) and data manipulation in administrative billing data (right panel)

Constituents aligned with the ruling party pay less for power

The large wedge between actual electricity consumption and reported consumption from bills implies an electricity subsidy selectively conferred to politically aligned constituencies. The size of the implied subsidy from manipulation of the billed data is large. In constituencies aligned with the ruling party, consumers are billed for only about 60% of their actual electricity usage.

Mechanisms of billing manipulation

The scale of data manipulation observed in this study suggests a coordinated effort at the local billing centre level. Billing centres in India are vulnerable due to the manual process of meter reading and data entry, where meter readers manually record usage and input it into computer systems, creating opportunities for manipulation. This vulnerability enables widespread underreporting of electricity, particularly in politically connected constituencies, a mechanism made possible by the close relationships between local politicians and billing centres under their purview (Chhibber et al. 2004). Alarmingly, utilities in 25 other Indian states share similar weaknesses (Gulati and Rao 2007). This paper also uncovers the same patterns of overconsumption by connected constituents using nighttime lights data across other states and elections in India.

Welfare losses from corruption in the Indian electricity sector are staggering

A major contribution of this paper is its ability to quantify welfare losses—something that is difficult to measure in corruption research (Khwaja and Mian 2007). While politically connected constituents may benefit from illicit electricity subsidies in the short run ($2.7 billion in consumer surplus), they face longer-term consequences. The underreporting of electricity consumption strains the utility's finances to the tune of $3.5 billion, leading to frequent outages due to its limited ability to supply reliable electricity on insufficient revenue (Burgess et al. 2020, Mahadevan 2022). This study estimates a net welfare loss of $0.9 billion in West Bengal alone, but the true efficiency losses are likely even greater. These figures do not account for the opportunity cost of utility bailouts (Chatterjee 2017) or the broader economic impact caused by the utility’s inability to meet electricity demand, which hampers productivity (Fried and Lagakos 2023).

Losses may extend nationwide

While the billing data analysis is available only for West Bengal, the use of satellite nighttime lights data between 2006 and 2022 indicates that similar patterns may exist across other Indian states. The broader inefficiencies caused by political manipulation in electricity distribution could extend nationwide, further amplifying the welfare losses observed in this study.

Policy reforms can improve efficiency and accountability in Indian electricity

This paper suggests several policy measures that could address these inefficiencies. The ability to quantify losses from corruption is crucial because it provides a clear, measurable cost of political corruption, which policymakers can use to push for reforms.

Focusing on increasing transparency and accountability in the electricity sector may be an effective method to combat corruption in the sector. Smart meters, regular audits, and independent regulatory oversight are essential to reducing political manipulation.

1. Transparency through technological solutions: smart meters and other advanced metering infrastructure could help address the problem by providing tamper-proof records of electricity consumption (Ahmad et al. 2024). This would make it more difficult for local billing centers to manipulate data.

2. Public engagement: educating citizens about the connection between what they pay for electricity and its subsequent quality (Mahadevan 2022, Burgess et al. 2020), as well as the economy-wide consequences of the large utility-level financial losses, is crucial.

Conclusion: Political favouritism creates major economic losses

My research quantifies how political manipulation in India's electricity sector distorts demand and creates substantial welfare losses. Ensuring transparency, accountability, and fairness in electricity provision is crucial for more equitable and efficient economic development. These findings highlight the profound negative impact that patronage politics can have on both the economy and the equitable distribution of public services.

References

Ahmad, H F, A Ali, R C Meeks, Z Wang, and J Younas (2024), “Down to the wire: Leveraging technology to improve electric utility cost recovery,” Unpublished manuscript.

Burgess, R, M Greenstone, N Ryan, and A Sudarshan (2020), “The consequences of treating electricity as a right,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 34(1): 145–169.

Calonico, S, M Cattaneo, and R Titiunik (2015), “Rdrobust: An R package for robust nonparametric inference in regression-discontinuity designs,” R Journal, 7(1): 38–51.

Chatterjee, E (2017), “Reinventing state capitalism in India: A view from the energy sector,” Contemporary South Asia, 25(1): 85–100.

Chhibber, P, S Shastri, and R Sisson (2004), “Federal arrangements and the provision of public goods in India,” Asian Survey, 44(3): 339–352.

Fried, S, and D Lagakos (2023), “Electricity and firm productivity: A general-equilibrium approach,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 15(4): 67–103.

Hicken, A (2011), “Clientelism,” Annual Review of Political Science, 14(1): 289–310.

Khwaja, A, and A Mian (2005), “Do lenders favor politically connected firms? Rent provision in an emerging financial market,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120(4): 1371–1411.

Mahadevan, M (2022), “You get what you pay for: Electricity quality and firm response,” Unpublished manuscript.

Mahadevan, M (Forthcoming), “The price of power: Costs of political corruption in Indian electricity,” American Economic Review. Available here.

Min, B, and M Golden (2014), “Electoral cycles in electricity losses in India,” Energy Policy, 65: 619–625.