Increases in local mineral wealth raise both the likelihood of criminally charged politicians entering office and asset accumulation among incumbents

In 2011, Shehla Masood, a prominent environmental activist, was shot by a hired hitman in Bhopal, following her work to expose alleged illegal diamond-mining activity alarmingly close to Madhya Pradesh’s Panna Tiger Reserve. While India’s premier investigative agency, the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), laid blame for the incident on a ‘love triangle’, Masood was only one of dozens of environmental activists murdered each year for exposing illegal activities in the mining sector.

India’s mining industry is no stranger to corruption scandals. In Karnataka, the Bellary mining racket operated for years, costing the Government of India at least US$2 billion in mining royalties. At their most brazen, mine operators moved the stones marking the border between the states of Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka to expand the area in their mineral license. Nearly half of the iron ore exported by the state of Goa is thought to be illegally mined. The situation has become sufficiently dire that the Supreme Court of India has at various times banned all mining activity in various Indian states. The reputation of the global mining industry is not much better.

Why is the mining sector tied to corruption?

The very nature of the mining industry exposes it to the risk of corruption. Mines are geographically small, they produce tremendous rents,1 and their operation depends on a range of government inputs, such as prospecting and drilling licenses and environmental clearances. Mining in developing countries almost always operates in a legal grey space – the huge return to expanding mines illegally or shirking on environmental compliance creates substantial opportunity for graft.

The concentration of rents makes it privately advantageous for politicians and mine owners to work together. Bribes are paid, clearances are granted, and profits are made. Generating comparable rents from more dispersed sectors is much more costly to politicians; in the mining sector, only a small number of people need to be involved to secure tremendous rents.

Testing the impact of mining on political behaviour

We set out to empirically test whether mining rents lead to worse political outcomes. Our idea was to examine whether political behaviour changes in places that are experiencing mining booms (Asher and Novosad 2020). India is an ideal laboratory for such a test, with 31 different minerals dispersed in geological deposits throughout the country. At any given time, some polities can be experiencing mining booms while others are experiencing busts.

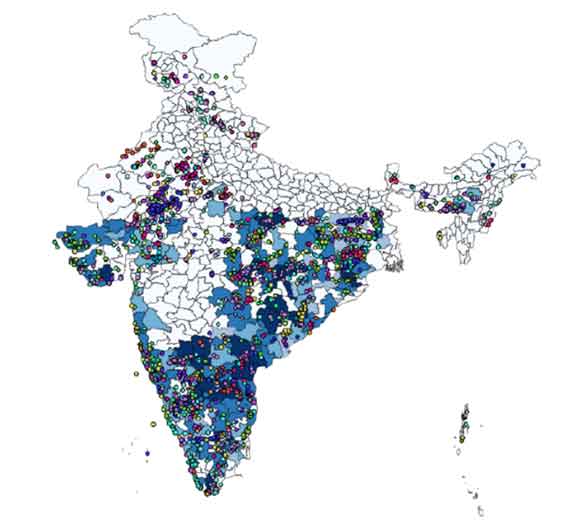

Figure 1 Deposit locations and mineral production across India

Notes: Districts are shaded in blue according to their mineral production, where the darkest blue have the most mineral output. The dots indicate mineral deposits of different types.

We mapped changes in mineral rents (proxied by changes in ‘exogenous’ global prices, which are independent of local political and economic trends) to political constituencies. When the global prices of the minerals extracted in a constituency rise, we infer that local mineral rents are likely to be rising – and with them, the returns to illegal mining and corruption. We examine the effect of these mining rent booms on the characteristics and behaviour of elected politicians. Since 2003, all politicians contesting elections in India must submit affidavits which record their education, assets, and any open criminal charges that they are facing – about a third face at least one criminal charge, and about a tenth face at least one charge for a violent crime. We drew our study outcomes (for the period 2003–2018) from these affidavits.

Mineral rent booms make criminal politicians more likely to be elected

We found substantial effects of mineral rents on the likelihood of criminally-charged politicians entering office. A doubling in the value of local mineral wealth (not uncommon in the 2000s commodity booms) increased the likelihood of a criminal politician entering office by 10 percentage points (a 30% increase). The effect was particularly strong for politicians charged with violent crimes – reflecting the thuggish nature of legislative politics in India’s mining constituencies.

This is a form of ‘adverse selection’. When the returns to illegal behaviour in office rise, politicians with criminal histories are more likely to end up in office. It is hard to know the exact mechanism through which this happens. We think it is likely that criminal politicians are working harder to enter office, and may even be facilitated by their parties, who benefit from the access to black money (Vaishnav 2017). We can at least rule out systematic preferences for criminal politicians among voters, or a lack of voter interest – if anything turnout is higher, and elections are more competitive during mineral rent booms.

Mineral rent booms lead to asset and crime increases among elected politicians

We can exploit the timing of mineral rent shocks to examine a distinct form of bad politician behaviour. By examining mineral rent price changes that occur after politicians have been elected, we can examine the incentive effect of a politician having access to higher mineral rents. We find that a doubling of local mineral wealth is associated with about a 25% increase in the assets of the politician who is in legislative office at the time of the boom. There are no effects on runners-up in the previous election, indicating this is not a general local wealth effect from mining activity. It is the elected politician who is making all the profits.

We also find that politicians are disproportionately charged with new crimes when rent booms take place during their terms. We call this the ‘moral hazard’ channel – on average, any given politician behaves worse when the opportunities for corruption are greater.

Implications

The moral hazard and adverse selection channels have different implications for mitigating the political harm from mineral extraction. The adverse selection channel implies that better institutions are needed to prevent bad actors from gaining office precisely when it is most important to elect good ones. Increasing voter information appears to be one way to help prevent the election of criminal politicians (George et al. 2018).

The moral hazard channel implies that politicians of all stripes need to be monitored more carefully while they are in office. Transparency around the cosy relationship between mining companies and politicians is essential since most of the deals underlying criminal activity in the mining sector are well-hidden. But this transparency is hard to achieve, since politicians and firms are all benefitting from keeping the current arrangements in the shadows.

A promising approach being undertaken in India is the use of satellite imagery to detect open-cast mines that have expanded beyond their licensed boundaries, through the Mining Surveillance System (MSS). An early version of the MSS had an Android application that purportedly allowed any citizen to examine local mine license boundaries and compare them to satellite images. While this would seem to be an extremely promising innovation and tool for civil society, we were never able to get the app to work, and there is no longer any mention of it on the site of the Ministry of Mines. Indeed, it remains very difficult to obtain georeferenced data on the boundaries of mines in India. Making these maps open to the public would be a major first step in improving transparency and limiting corruption and illegal mining.

Editors’ note: This column was written with the assistance of Aditi Bhowmick and was published in collaboration with Ideas for India.

References

Asher, S and P Novosad (2020), "Rent-seeking and criminal politicians: Evidence from mining booms", conditionally accepted at Review of Economics and Statistics.

George, S, S Gupta and Y Neggers (2018), "Coordinating Voters against Criminal Politicians: Evidence from a Mobile Experiment in India", Working paper.

Vaishnav, M (2017), When crime pays: Money and muscle in Indian politics, Yale University Press.

Endnotes

1 Rents’ here refer to a surplus value (can also be thought of as supernormal profit) after accounting for costs and normal returns.