Municipalities with oil pipelines in Mexico saw a 30% increase in cartel presence after the war on drugs began, resulting in severe economic and social impacts.

Government crackdowns can sometimes have unintended consequences and Mexico’s war on drugs is a prime example. Launched at the end of 2006 by President Felipe Calderón, the military campaign aimed to dismantle powerful drug cartels and reduce violence (Dell 2015). Instead, it caused a dramatic increase in both violence and the diversification of criminal activities. One of the most unexpected outcomes was the surge in oil theft, a crime that was previously limited to small-scale operations but evolved into a highly organised, large-scale enterprise.

In recent research, we shed light on how and why this shift occurred, focusing on the criminal logic behind cartel decisions to enter the oil theft market (Battiston et al. 2024). When the state intensified its anti-drug policies, cartels didn’t just suffer setbacks in the drug trade - they adapted. Our findings provide a striking reminder of how criminal organisations, much like businesses, respond strategically to external pressures and diversify their activities when their primary market becomes too risky or unprofitable.

Mexican cartels as criminal entrepreneurs

One of the key insights from the study is that cartels, especially those on the fringes of the drug market, were quicker to pivot to oil theft than the larger, established players. The Zetas, for example, were once a paramilitary group that evolved into a drug cartel, but they were not as entrenched in the drug trade as the Sinaloa or Gulf cartels. This made them more agile in responding to new opportunities. This pattern is reminiscent of “leapfrogging” in legitimate markets, whereby “challengers” in more established sectors are faster to seize new profit opportunities.

In the case of the Mexican war on drugs, challenger cartels exploited weaknesses in Mexico’s oil infrastructure, particularly Pemex pipelines, which crisscross the country and are relatively easy to tap. Cartels, armed with information obtained through bribery, tapped into these pipelines, selling stolen oil on the black market. The scale of this operation grew rapidly: by 2018, oil theft was costing Mexico between $1 billion to $2 billion per year (Duhalt 2017).

A new criminal business model after the war on drugs

The cartel expansion into oil theft illustrates how organised crime can pivot when faced with state repression. Before the crackdown, oil theft was largely the work of small, local groups known as huachicoleros. These groups lacked the resources to engage in oil theft at scale. Cartels industrialised the process, using advanced technology and their logistical networks to move vast quantities of stolen oil.

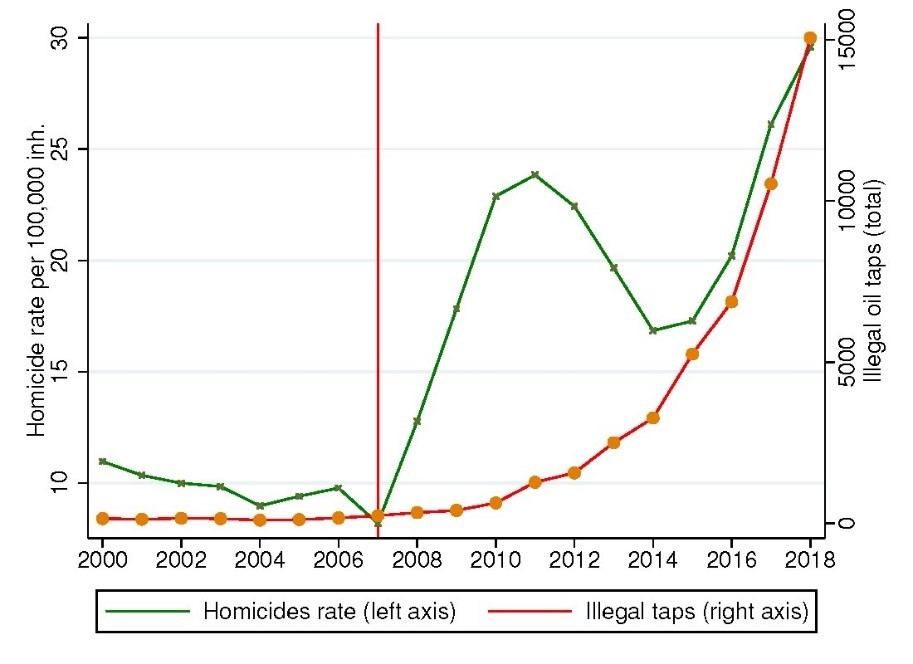

Between 2007 and 2018, the number of illegal taps into Pemex pipelines exploded. Figure 1 shows that the number of oil taps surged from a few hundred in 2006 to over 15,000 in 2018, while the homicide rate tripled, climbing from 8 to 29 per 100,000 inhabitants. Instead of weakening cartels, anti-drug operations pushed them into new, highly profitable ventures that destabilised the country.

This shift didn’t just lead to an increase in cartel wealth—it reshaped the landscape of organised crime, allowing newer criminal organisations like the Zetas to grow at the expense of more established cartels.

Figure 1: The Mexican war on drugs: homicides and illegal oil taps

Notes: This figure plots the homicide rate in Mexico (left scale) and the number of illegal oil taps (right scale) over the period 2000– 18. The vertical line represents the war on drugs.

Geographic and political drivers of the shift in cartel behaviour

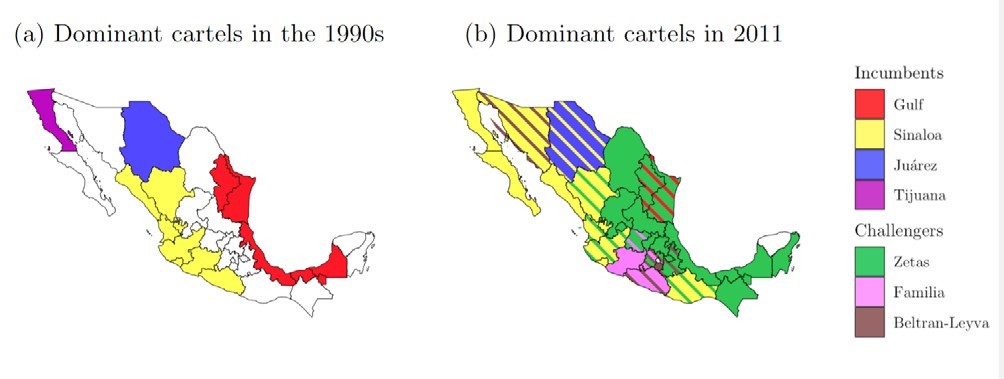

Our empirical findings underscore the importance of geography and politics in this shift. Municipalities with oil pipelines saw a 30% increase in cartel presence after the war on drugs began, while those without pipelines did not experience the same surge. In particular, the increase was driven by younger, challenger cartels like the Zetas and the Familia Michoacana, who rapidly expanded into regions with oil infrastructure; see Figure 2.

Figure 2: Areas of influence of Mexican cartels

Notes: Panels (a) and (b) show the areas of influence of Mexican drug cartels in the 1990s and in 2011, based on information from Beittel (2011) and Trejo and Ley (2020).

Examining the impact of the war on drugs on large-scale oil-thefts in Mexico

To identify the (causal) effect of the war on drugs on large-scale oil thefts by drug cartels, we employed two main strategies. First, we compared cartel presence and other socio-economic outcomes between municipalities with oil pipelines and those without, before and after the war on drugs. This allowed us to isolate the impact of the crackdown on cartel activity in municipalities where oil theft became a lucrative alternative.

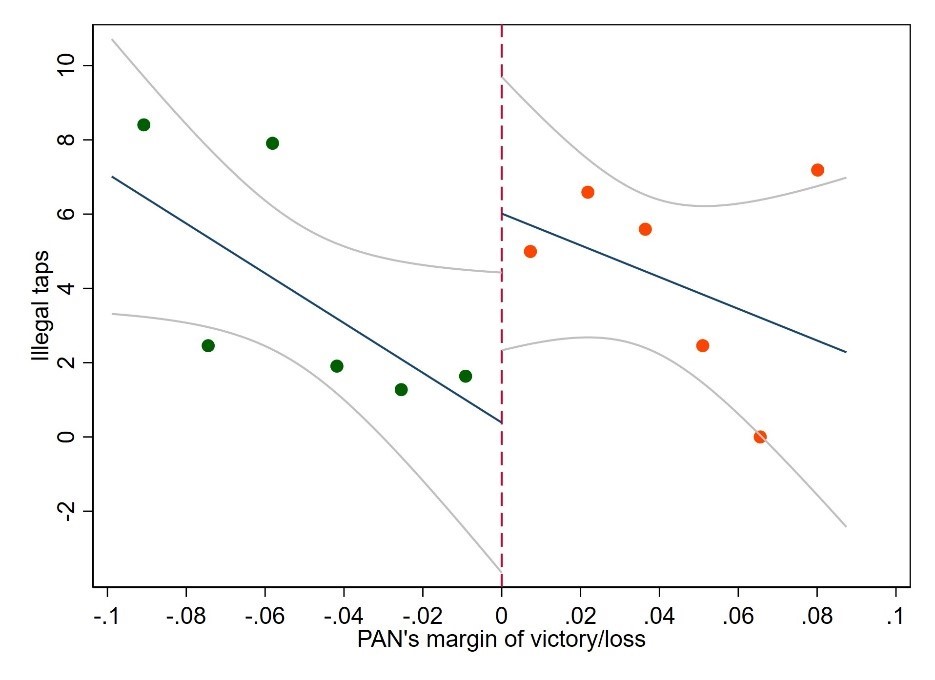

Second, we examined municipalities where the antidrug policy was more politically supported; in particular, we compared municipalities where the progovernment PAN party won or lost the first electoral round after the outbreak of the war on drugs (2007-2009). As illustrated in Figure 3, municipalities where PAN narrowly won the elections saw a larger increase in illegal oil taps - by 6.6 taps per year - compared to areas where PAN narrowly lost.

Figure 3: PAN’s margin of victory and illegal taps

Notes: This figure shows the relationship between the PAN’s margin of victory at the 2007–9 electoral round (horizontal axis) and the number of illegal taps (vertical axis) across municipalities. The scatter plot represents averages over equally spaced bins of the margin of victory. The predicted relationship and confidence intervals are based on a linear regression.

What’s equally striking is that this expansion into oil theft did not lead to the same levels of violence as the drug trade. Municipalities with pipelines did not see the same spike in homicides, largely because oil theft brought less inter-cartel competition as challenger cartels moved into oil theft while incumbent cartels remained in the drug trade, in turn avoiding violent turf wars. However, the economic and social impacts were still severe. In areas with more oil theft, school attendance among children under 15 dropped significantly, indicating a diversion of young people into the criminal economy.

Broader policy implications on how to manage organised crime

The study provides crucial lessons for policymakers confronting organised crime. It demonstrates how focusing narrowly on one criminal market - such as drugs - can lead to the emergence of new, equally damaging forms of crime. Cartels, much like legitimate businesses, are dynamic organisations capable of shifting their operations when one area becomes too risky or unprofitable. The Mexican experience highlights the dangers of fragmented policies that fail to consider the broader criminal ecosystem.

Instead of reducing cartel activity, the war on drugs merely pushed cartels to innovate. The rise of oil theft offers a cautionary tale for policymakers: comprehensive strategies that address the entire spectrum of criminal activity are essential. Isolated crackdowns on one sector can have the unintended consequence of pushing crime into other areas as cartels adapt to survive and thrive.

Conclusion: Rethinking organised crime policies

The lessons from Mexico’s war on drugs go beyond oil theft or even cartels. They speak to a larger truth about criminal enterprises: like legitimate businesses, they respond to risks and opportunities. Cartels diversified into oil theft because drug trafficking became too risky, but the state’s crackdown did little to diminish the root causes of organised crime or its capacity to reinvent itself.

As governments around the world continue to battle organised crime, they must recognise that criminals will always adapt. Fighting crime in one area without a broader strategy can simply shift the problem elsewhere. Mexico’s experience shows that unless policymakers target the entire network of criminal activity, they risk creating new problems even as they try to solve old ones.

References

Battiston, G, G Daniele, M Le Moglie, and P Pinotti (2024), “Fuelling organised crime: The Mexican war on drugs and oil theft,” The Economic Journal, forthcoming.

Beittel, J S (2011), “Mexico’s drug trafficking organizations: Source and scope of the rising violence,” Report for Congress, Congressional Research Service.

Dell, M (2015), “Trafficking networks and the Mexican drug war,” American Economic Review, 105(6): 1738–1779.

Duhalt, A (2017), “Looting fuel pipelines in Mexico,” Issue Brief 06.23.17, Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy.

Trejo, G, and S Ley (2020), “Why cartels went to war: Subnational party alternation, the breakdown of criminal protection, and the onset of inter-cartel wars,” in Votes, Drugs, and Violence: The Political Logic of Criminal Wars in Mexico, pp. 69–112, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.