Greater competition from improved roads that connected markets in Ethiopia increased the divide between firms in the formal and informal sectors.

Informality and the role of competition

Recent research has emphasised the important role of the informal sector in job creation and structural transformation in developing countries (Diao et al. 2024). In the manufacturing sector, although formal firms contribute more to productivity growth, informal firms employ a larger share of the workforce. However, few analyses have asked how policy reforms or external shocks impact informal firms differently relative to formal firms (Dix-Carneiro et al. 2021) and how this shapes the composition of the manufacturing sector.

In this article, we discuss the effects of increased competition from an improvement in roads in Ethiopia - resulting from an extensive infrastructure development programme that boosted connectivity to other domestic markets. Our analysis focuses on formal and informal manufacturing firms, and we use firm level data from the Large and Medium Manufacturing Industry Survey (LMMS) and the Survey of Small-scale Manufacturing Industries (SSIS), respectively. We highlight that the benefits of road infrastructure development programmes may not accrue uniformly to firms in both sectors.

The Road Sector Development Programme in Ethiopia

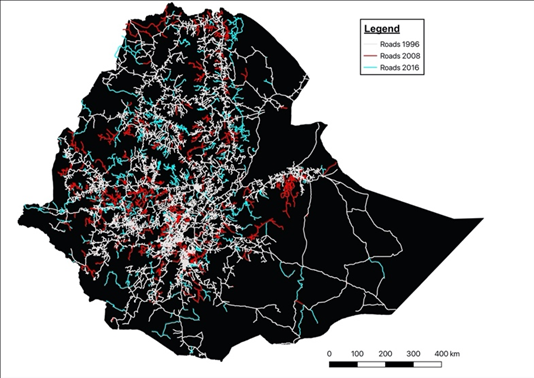

The Road Sector Development Programme (RSDP) is an ambitious investment programme that has been implemented in Ethiopia since 1997, and is still ongoing. Its objective is to rehabilitate existing Ethiopian roads and construct new road networks (Figure 1). The Ethiopian road network increased from 26,550 km in 1997 to 113,066 km in 2016, while the proportion of the country's rehabilitated roads increased from 22% to 72% in the same period. Therefore, road density per 100 square km rose significantly from 21.1 km in 1997 to 102.8 km in 2016.

This large-scale development project has attracted particular interest among researchers analysing the impacts of infrastructure investments. Research has shown that the RSDP was a key driver of agricultural productivity (Adamopoulos 2024), spurred business activity (Fiorini et al. 2021) and stimulated structural transformation from agriculture to the services sector (Fiorini and Sanfilippo 2022, Moneke 2020).

Figure 1: Ethiopian road network under the RSDP.

Notes: Roads in white represent the state of the road infrastructure in Ethiopia before the start of the RSDP. Roads in red and blue show upgrades completed during different phases of the implementation of the programme. Source: Authors’ calculation on the RSDP data.

Roads and increased competition in domestic markets

In our recent work (Perra et al. 2024), we capture changes in competition faced by firms from an increase in road connectivity. To do this, we develop a measure in the spirit of the market-access approach widely used in previous research (Donaldson and Hornbeck 2016).

We begin by treating each Ethiopian district as a local market. For each district and industry of a firm in a given year, we construct a weighted average of the inverse of travel times to all other districts given the road network and travel speed (which depends on the quality of the road), where the weights are total production in the district and industry. Variation in this measure captures both variation in production in the firm’s industry in connected markets, and variation in travel times as roads are expanded and improved. It is thus a time-varying measure of changes to competition faced by a firm as the road network evolves. We refer to this measure as consumer market-access to convey the idea that it measures the availability of alternatives available to consumers in a particular industry.

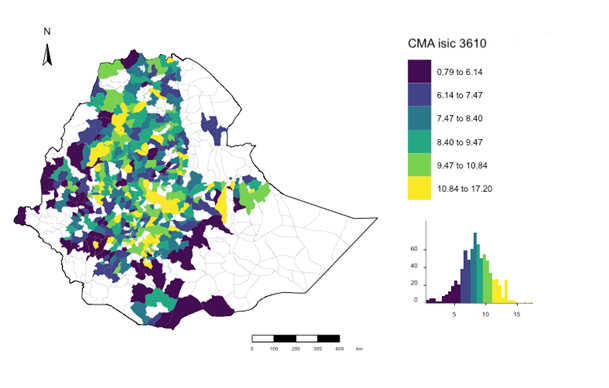

Take a given sector, furniture, as an example (Figure 2). Consumers in a remote district A have few options other than to buy furniture from local firms. But, with improvements in connectivity with other districts where furniture firms are active (i.e. an increase in the consumer market-access for furniture firms in district A), consumers in A have better access to furniture products produced in connected markets. Thus, the increase in consumer market-access translates into more competition for furniture firms in District A.

Figure 2: Consumer market-access in the furniture industry.

Notes: The map reports the simple average of CMA across different districts during the sample period in the furniture industry, which corresponds to the ISIC code 3610. Source: Authors’ calculation.

Impacts of competition on formal and informal firms

We first show that an increase in consumer market-access is associated with greater competition. It reduces firm markups and lowers the likelihood that a firm operates in the informal sector, consistent with increased competition and potential selection effects, whereby less productive informal firms exit.

Next, we show that the impact of consumer market-access on firm outcomes varies substantially across formal and informal sector firms. Among formal firms, a one standard deviation or 50% increase in consumer market-access corresponds to a 6.5% increase in labour productivity, almost twice as large as the effect for the sample taken as a whole. For formal firms, increases in consumer market-access are linked to improvements in capital-intensity, investment in physical assets and wages.

For informal firms, there is no relationship between consumer market-access and labour productivity. If anything, the relationship is weakly negative. An increase in consumer market-access reduces the capital-labour ratio and investment in informal firms. In addition, exploiting information on the level of education of each individual worker within a firm, we show that among informal firms, an increase in consumer market-access is associated with a change in worker composition - a larger share of workers without primary education and a smaller share with higher education.

The role of financial markets

These findings are consistent with a framework where firms in the formal sector compete nationally while the informal sector operates locally. An increase in competition from better domestic connectivity results in an increase in the elasticity of demand for each formal sector product variety – increases in the price of a product lead to larger falls in demand than before. This leads to a decrease in product varieties produced, a decrease in firm markups and an increase in firm size in the formal sector (Desmet and Parente 2010). The increase in firm size means that the return to investments in physical capital typically associated with innovative activity and technological upgrading is larger, making such investments more attractive.

In a capital-constrained environment, where formal firms can access formal credit and informal firms resort to informal sources, the increase in demand for capital in the formal sector drives up the cost of capital for informal firms. This results in lower (higher) capital input, capital intensity, investments in physical capital and labour productivity in the informal (formal) sector. We test for evidence of this mechanism and show that the differential effects of consumer market-access on labour productivity of formal versus informal firms hold particularly in (a) industries with greater reliance on credit (as proxied by the share of interest paid over sales) and (b) in districts without any bank branches where credit is most likely to be constrained.

Policy implications for infrastructure investments and the informal sector

This study connects two areas of high priority for public policy: the performance of the informal sector, which is a pervasive feature of the developing world and plays a central role in structural transformation, and infrastructure investment, a critical driver of economic growth. Understanding differential responses of the formal and informal sectors to large infrastructure projects is key to development policy design and implementation. Overall, our results emphasise that competition from better connectivity due to road infrastructure improvements may disadvantage the informal sector as it disciplines the formal sector.

References

Adamopolus, T (2024), “Spatial integration and agricultural productivity: Quantifying the impact of new roads,” AEJ: Macroeconomics, forthcoming.

Desmet, K, and S L Parente (2010), “Bigger is better: Market size, demand elasticity, and innovation,” International Economic Review, 51(2).

Diao, X, M Ellis, M S McMillan, and D Rodrik (2024), “Africa’s manufacturing puzzle: Evidence from Tanzanian and Ethiopian firms,” The World Bank Economic Review.

Dix-Carneiro, R, P K Goldberg, C Meghir, and G Ulyssea (2021), “Trade and informality in the presence of labor market frictions and regulations,” NBER Working Papers No. 28391.(VoxDev article.)

Donaldson, D, and R Hornbeck (2016), “Railroads and American economic growth: A market access approach,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131(2): 799–858.

Fiorini, M, and M Sanfilippo (2022), “Roads and jobs in Ethiopia,” World Bank Economic Review, 36(4): 999–1020.

Fiorini, M, M Sanfilippo, and A Sundaram (2021), “Trade liberalization, roads and firm productivity,” Journal of Development Economics, 153: 102712. (VoxDev article.)

Moneke, N (2020), “Can big push infrastructure unlock development? Evidence from Ethiopia,” Mimeo.

Perra, E, M Sanfilippo, and A Sundaram (2024), “Roads, competition, and the informal sector,” Journal of Development Economics, 171.