What are the effects of trade amidst a large informal sector? New research studies a model tightly connected to data on firms and workers in Brazil

Read more about economic research on the informal sector in our VoxDevLit on Informality.

The informal sector accounts for a large part of the economy in most developing countries, yet it is understudied in economics. The informal sector captures, broadly speaking, all activities that are invisible to the government: operation of firms that are not registered with tax authorities and/or employment of workers who are not covered by labour market regulations and do not receive benefits or severance payments when laid off.

Recent empirical work studying trade liberalisation episodes in developing countries suggests that shifts into and out of informality constitute important margins of labour market adjustment to economic shocks (Goldberg and Pavcnik 2003, McCaig and Pavcnik, 2018 Dix-Carneiro and Kovak 2019, Ponczek and Ulyssea 2020). Notwithstanding this recent body of research, we know little about the overall labour market and welfare effects of trade liberalisation and other economic shocks in settings characterised by extensive labour market regulation, weak enforcement of this regulation, and informality, as in developing economies. We address this gap with our recent paper (Dix-Carneiro et al. 2021) by developing a structural equilibrium model of trade and informality.

Building and estimating our model

Our model features two broad sectors – tradable and non-tradable – that are connected through input-output linkages. Within each sector, heterogeneous firms choose whether to operate in the formal or informal sectors, subject to labour market frictions and a rich institutional setting, such as a minimum wage, firing costs, and value-added and payroll taxes. Critically, these regulations are not perfectly enforced by the government, providing incentives for small firms to opt for informality. We estimate the model using multiple data sources, including matched employer-employee data from formal and informal firms and workers in Brazil, household surveys, manufacturing and services censuses, and customs data. We use the estimated model to perform counterfactual experiments to understand and quantify the effects of trade openness on informality, unemployment, welfare, productivity, and wage inequality.

We consider four scenarios for Brazil’s level of trade openness: (a) Benchmark, which corresponds to the Brazilian economy in 2003, (b) Moderate, which corresponds to a 20% reduction in existing trade barriers, (c) High, which corresponds to a 40% reduction in trade barriers, and (d) Autarky, which corresponds to a large increase in trade barriers, making both imports and exports prohibitive.

The sector-specific effects of trade openness

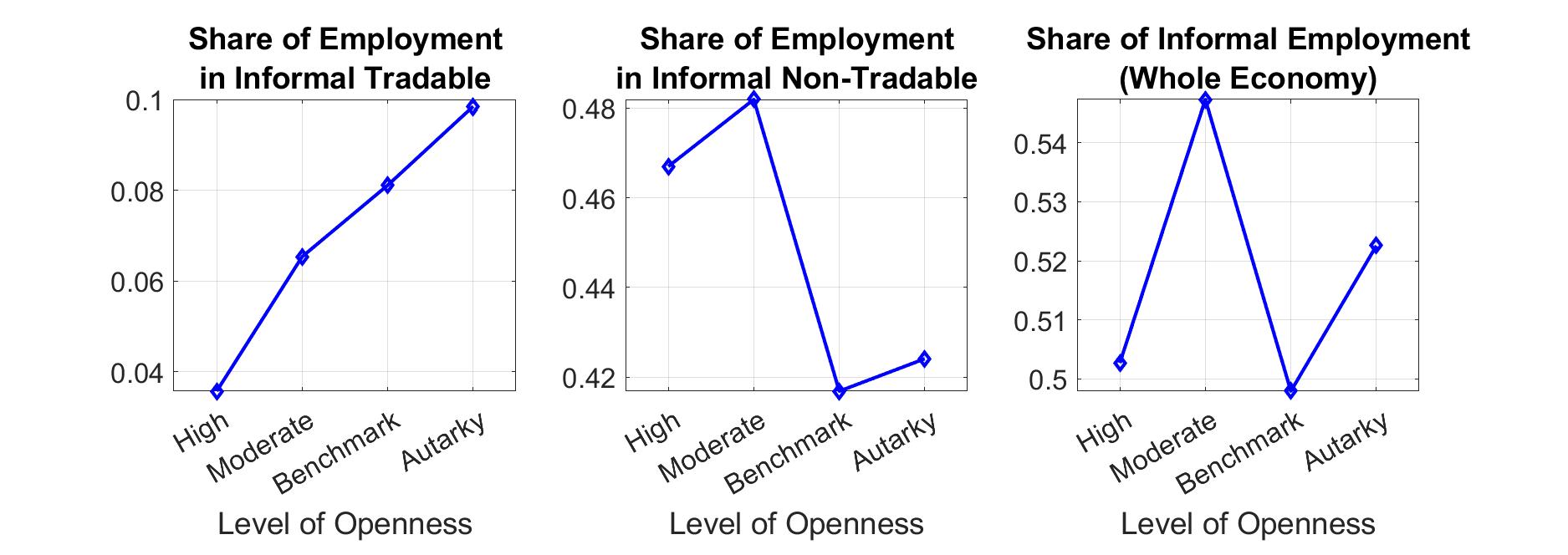

Figure 1 shows that trade openness leads to a strong reduction in informality in the tradable sector. Moving to a High level of trade openness more than halves the share of employment in the informal tradable sector (from 8.1% to 3.6%).1 As a result of declining import costs, domestic firms face stiffer foreign competition, which pushes low-productivity formal firms to informality, but also increases exit of low-productivity informal firms. Empirically, the latter effect dominates.

Figure 1 Trade openness and informality

By contrast, openness leads to increased informality in the non-tradable sector, caused by the increase in total demand for non-tradable goods, both by consumers (due to higher real income) and by an increase in usage of intermediate non-tradable inputs mostly from exporters. Higher demand encourages productive informal firms to expand and formalise, but also encourages entry of low-productivity informal firms, which is the dominant force.

Considering both sectors together, moderate reductions in trade barriers lead to a net increase in the share of informal employment. This almost reverts to the baseline level when we consider a High level of trade openness. This result may explain why informal employment has not declined substantially in developing countries, despite their rapid integration in world markets in the past three decades (World Bank 2019).

The effect of trade on wage inequality depends on the inclusion of the informal sector

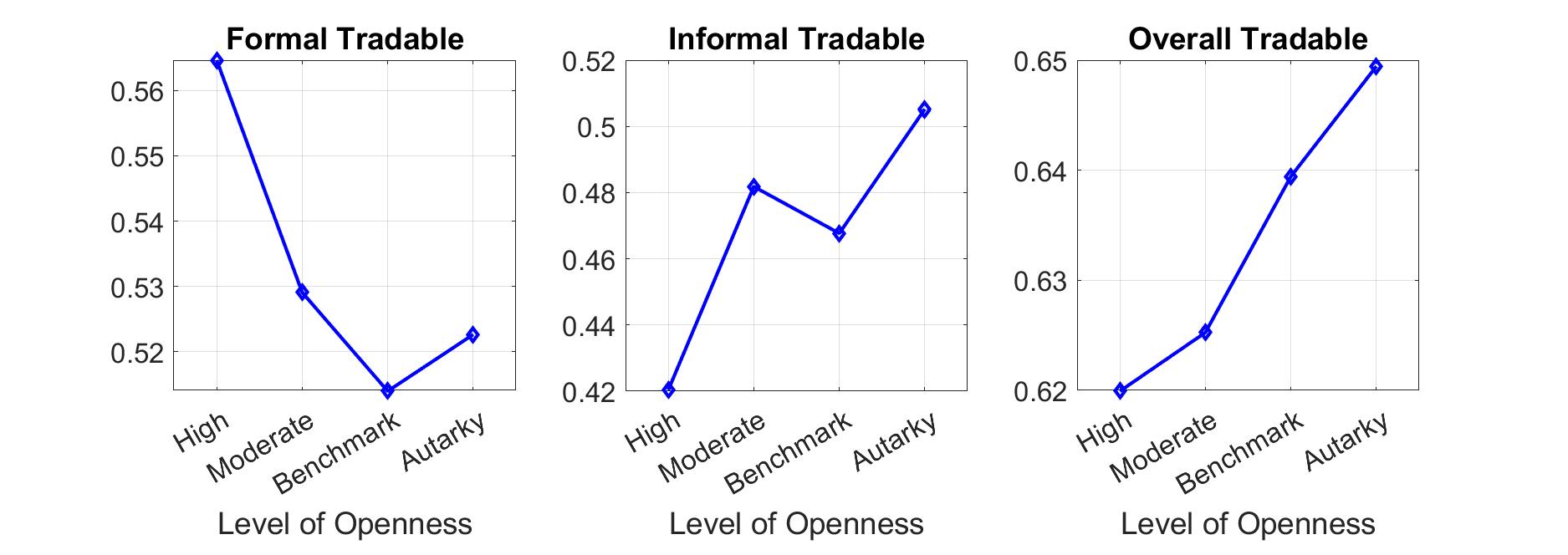

A large literature has focused on the effect of openness on wage inequality, which we revisit within our framework.2 Figure 2 shows that wage inequality (measured by the standard deviation of log-wages) within the formal tradable sector increases by 10% as we move to a High level of trade openness. As in previous work, we find that greater openness leads to a higher exporter wage premium, driving an increase in wage dispersion within the formal tradable sector.

However, the informal tradable sector displays the opposite pattern, with a decline in wage inequality. This is a consequence of market exit by low productivity informal firms, which pay low wages. Most importantly, the distance between average wages in the informal and formal sectors is reduced, so that, once we consider both formal and informal workers together, trade openness leads to a reduction in overall wage inequality. This finding contrasts with what is typically found in the literature, highlighting the importance of incorporating the informal sector in analyses.

Figure 2 Trade openness and wage inequality (standard deviation of log-wages)

Unemployment increases monotonically when we move from the Benchmark to High level of openness, with moderate effects (a 6% increase in the number of unemployed workers). This finding follows from a positive relationship between aggregate firm-level turnover and unemployment, and two opposing forces:

(1) The size distribution in both tradable and non-tradable sectors shifts toward larger firms

(2) A shift in employment toward exporters in the tradable sector.

The first pushes aggregate turnover down, as larger firms tend to have lower turnover. The second pushes turnover up because, conditional on size, exporters have higher turnover (both in the data and in the model). The second effect dominates and turnover in the tradable sector increases with openness.

Productivity and welfare effects

Even though unemployment increases, and informality might increase (or remain nearly stable), we find that trade openness has strong positive effects on productivity and welfare.

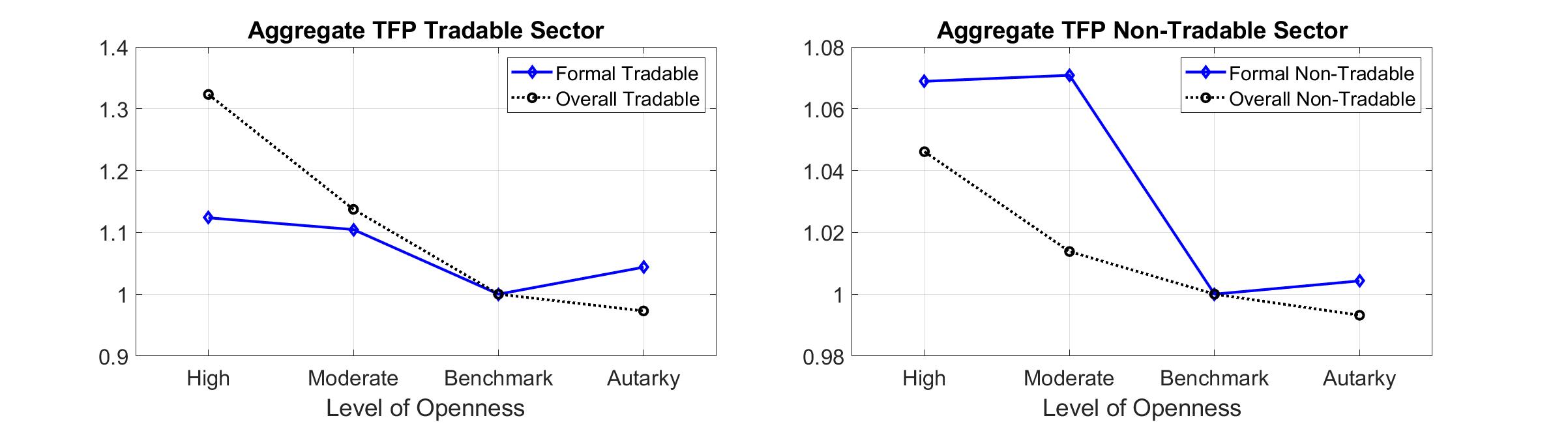

As expected, reductions in trade costs lead to gains in aggregate total factor productivity (TFP) in the formal tradable sector (of 12% in the High openness case). However, this largely underestimates the gain in productivity in the tradable sector as a whole (Figure 3). Once we account for both formal and informal sectors, trade openness generates productivity gains of up to 32%. Accounting for informality reveals a new channel leading to increased productivity: trade openness displaces highly unproductive informal firms, allowing a reallocation of resources to more productive formal ones. The opposite pattern is found in the non-tradable sector (albeit at a much smaller scale): the effect of openness on overall aggregate productivity is smaller than the effect on the formal sector.

Considering the tradable and non-tradable sectors together, a movement towards a High level of trade openness leads to an increase in aggregate TFP of 7.6% in the formal sector, which goes up to 9.6% once we incorporate the informal sector. Finally, we find aggregate welfare (real income) gains amounting to 21% once a High level of openness is achieved.

Figure 3 Trade openness and aggregate total factor productivity (TFP)

Notes: All variables are normalised and relative to their values under the Benchmark level of openness.

The informal sector as a buffer

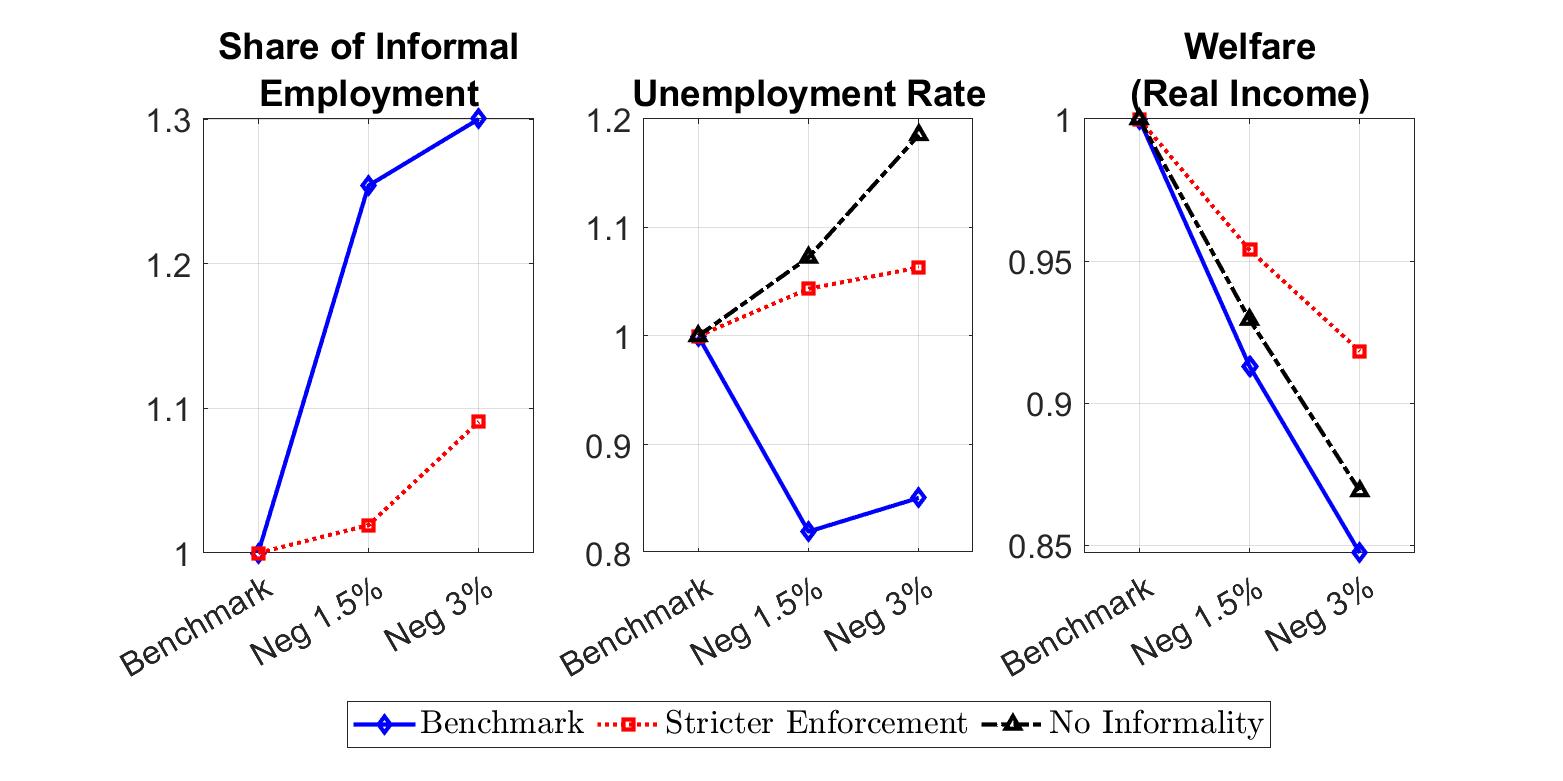

The informal sector is often thought as providing an important employment buffer following negative economic shocks. We examine this conjecture by simulating negative shocks to firms’ productivity distribution (i.e. supply driven recessions) of 1.5% and 3% under three scenarios: (a) Benchmark (the Brazilian economy in 2003), (b) the government implements a Stricter Enforcement of regulations policy leading to reduced informality, and (c) a complete informality ban (No Informality).

Although extreme and unlikely to be achievable in practice, the No Informality scenario is a theoretically interesting paradigm to contemplate through the lens of our model. Figure 4 shows that these ’recession’ shocks lead to higher informality but no unemployment effects in the Benchmark economy—consistent with the results of Dix-Carneiro and Kovak (2019). However, these shocks lead to significant increases in unemployment under the No Informality and Stricter Enforcement scenarios, with limited or zero informality effects, consistent with the results in Ponczek and Ulyssea (2020). These findings are therefore consistent with the hypothesis that the informal sector serves as an employment buffer. The question then is whether it also acts as a ’welfare buffer,’ avoiding greater welfare losses in face of negative shocks.

As the right panel of Figure 4 shows, the answer is no: the Benchmark economy (with the weakest enforcement policy) experiences the largest relative decline in real income in response to the negative shocks. This is because a certain degree of informality repression reinforces the ’creative destruction’ aspect of a negative productivity shock, driving out of the market inefficient informal firms and increasing aggregate TFP.

Figure 4 Negative productivity shocks, informality, unemployment and welfare

Notes: All variables are normalised and relative to their values under the Benchmark.

Conclusion

Our estimated model rationalises a number of findings reported in the empirical literature and reveals several novel patterns and insights.

First, the effects of trade on productivity are understated when the informal sector is left out, and this is particularly pronounced in the tradable sector. Second, we estimate large welfare gains from trade, which are robust to different scenarios in which informality is either completely or partially repressed. Third, we show that repressing informality increases productivity at the expense of welfare, while trade openness leads to the same productivity gains but also increases welfare. Fourth, trade increases wage inequality in the formal tradable sector, but this effect is reversed when the informal sector is accounted for in the analysis. Finally, while the informal sector acts as an ’employment buffer’ in face of negative shocks, it does not serve as a ’welfare buffer’. More generally, our results strongly indicate that it is key to carefully model both the informal sector and the non-tradable sector to obtain a more accurate and comprehensive picture of the effects of trade in developing countries.

Editors’ note: This article was published in collaboration with VoxEU.

References

Cosar, A, N Guner and J Tybout (2016) “Firm Dynamics, Job Turnover, and Wage Distributions in an Open Economy,” The American Economic Review 106: 625-663.

Dix-Carneiro, R and B Kovak (2019) “Margins of Labor Market Adjustment to Trade,” Journal of International Economics 117.

Dix-Carneiro, R, P Goldberg, C Meghir and G Ulyssea (2021) “Trade and Informality in the Presence of Labor Market Frictions and Regulations,” NBER Working Paper 28391.

Goldberg, P and N Pavcnik (2003) “The response of the informal sector to trade liberalization,” Journal of Development Economics 72: 463–496.

McCaig, B and N Pavcnik (2018) “Export Markets and Labor Allocation in a Low-Income Country,” American Economic Review 108: 1899–1941 (see also the VoxDev column here).

Ponczek, V and G Ulyssea (2020) “Is Informality an Employment Buffer? Evidence from the Trade Liberalization in Brazil,” unpublished manuscript.

World Bank (2019) World Development Report 2019: The Changing Nature of Work, Washington, DC.

Endnotes

1 These results are consistent with the empirical findings of McCaig and Pavcnik (2018). They show that the Vietnamese manufacturing sectors that benefitted the most from the United States-Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement experienced substantial relative increases in formal-sector employment.

2 It is important to note that workers are homogenous in our model, and therefore wage inequality is entirely driven by differences across firms. In this respect, we follow an important stream of the literature that includes, among others, Cosar et al. (2016).