Bureaucratic output is negatively associated with monitoring and incentive schemes but positively associated with the autonomy of mid-level bureaucrats

The capabilities of the state shape the process of economic development. In studying the state, economists have long paid attention to the selection and incentives of both top-tier politicians and frontline workers, such as teachers, tax inspectors, and health workers. What has been relatively less studied is the vital middle-tier of civil servants, typically based in government ministries, whose day-to-day job is converting political decisions into actual policy (Finan et al. 2016). This is surprising given that this middle tier of civil servants is a key human resource and ultimately plays an important role in determining bureaucratic effectiveness and state capabilities.

Analysing management practices and performance

Our recent work tries to make progress on understanding what drives the effectiveness of bureaucrats in two important contexts in sub-Saharan Africa: Nigeria and Ghana (Rasul and Rogger 2016, Rasul et al. 2017). Working with the central civil services in each country, we have been examining whether the management practices that bureaucrats operate under correlate to the effective delivery of public services that they are responsible for.

In the Nigerian context, we hand-coded independent engineering assessments of project completion rates for 4,700 public projects (Rasul and Rogger 2016). For each of 63 civil service organisations tasked to implement these projects (including 10 ministries and 53 other Federal civil service organisations), we surveyed senior bureaucrats to elicit management practices in place for middle-tier bureaucrats, building on methods pioneered by Bloom and Van Reenen (2007) and Bloom et al. (2012).

Our more recent paper is a scientific replication of this work in Ghana (Rasul et al. 2017). While we address the same broad research questions linking the management practices bureaucrats operate under to bureaucratic performance, we do so while introducing some changes in the measurement of key variables. The first relates to measuring the output of bureaucracies. This is necessitated by the fact that civil service bureaucracies worldwide differ greatly in whether and how they collect data on their own performance. Unlike macroeconomic or household survey data, statistical agencies are typically not involved in measuring government effectiveness, and few international standards exist to aid cross-country comparisons.

In Ghana, we use quarterly and annual reports for each civil service organisation to build a database of 3,628 projects and tasks undertaken across 31 organisations during 2015. This allows us to build a comprehensive picture of what government bureaucracies actually do.

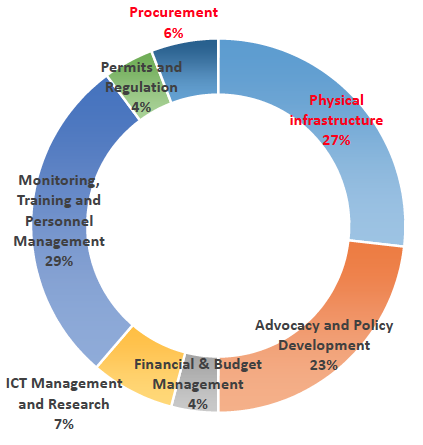

As Figure 1 shows, most of these projects are non-infrastructure projects, many of which are related to internal bureaucratic functioning rather than frontline public service delivery – the most common project type relates to human resource management (‘monitoring, training, and personnel management’). This reinforces the importance of understanding how the management practices that bureaucrats operate under relate to bureaucratic effectiveness.

Figure 1 What do bureaucracies do?

The second change from Nigeria to Ghana is an alternative approach to measuring management. While still anchored in the Bloom and Van Reenen (2007) and Bloom et al. (2012) methods, our approach in Ghana was designed to probe the sensitivity of results to differences in how such data are collected, and conceptual differences in the measurement of specific practices.

Our findings

Analysing this rich performance and management data together led us to three main insights that hold for both the Nigerian and Ghanaian bureaucracies.

1. There is considerable variation in performance across bureaucratic organisations within each country.

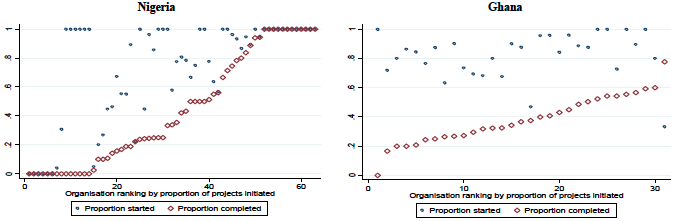

Figure 2 shows the variation in project completion rates across organisations in each country. There is huge variation in the performance of different government bureaucracies in each country. This variation occurs despite the fact that multiple organisations engage in similar project types, hires are assigned from the same pool of incoming bureaucrats, and many are located geographically close to one another in Abuja/Accra.1

Figure 2 Bureaucratic performance by organisation

2. There is huge variation in management practices across organisations.

In both Ghana and Nigeria, we focus on two dimensions of management practice: those capturing bureaucrats’ autonomy/flexibility, and those capturing incentives and monitoring for bureaucrats.2 For the autonomy index, we assume greater autonomy corresponds to better management practices (and similarly for the incentives/monitoring measure).

Figure 3 Management practices across bureaucracies

Figure 3 shows that, as with bureaucratic performance, there is high variation in practices across organisations. Again, this variation occurs despite the fact that all organisations in each country share the same colonial and post-colonial histories, are governed by the same civil service laws and regulations, are overseen by the same supervising authorities, are assigned new hires from the same pool of incoming bureaucrats each year, and are often located in close proximity to one another.

3. Autonomy is positively associated with bureaucratic output, but monitoring/incentives are negatively associated with bureaucratic output.

Since each organisation implements multiple project types, we are able to compare the relationship between management practices and output across organisations, holding constant the type of projects that each organisation implements.

In both Ghana and Nigeria, we find that:

- the autonomy index of management practices is robustly positively correlated with project initiation, full completion, and average completion rate;

- the incentives/monitoring index is robustly negatively correlated with all these measures of project completion.

Overall, in both settings, management practices for bureaucrats matter and are of economic significance. In terms of policy implications, the positive correlation of management practices related to autonomy with project completion rates supports the notion that bureaucracies could delegate some decision making to civil servants, relying on their professionalism and resolve to deliver public services. The evidence is less supportive of the notion that when bureaucrats have more agency, they are more likely to pursue their own, potentially corrupt, objectives.

The negative partial correlation between project completion rates and management practices related to the provision of incentives and monitoring of bureaucrats, is surprising and counter to evidence from private sector settings. Evidence on the impacts of performance-related incentives in public sector settings is mixed (often focusing on the impacts of specific compensation schemes to frontline workers). Ours is among the first evidence to suggest the possibility that such management practices negatively correlate to the output of the vital tier of civil service bureaucrats in multiple contexts. As such they serve as a useful check on the ‘New Public Management’ agenda sweeping through government bureaucracies, where the use of performance incentives is seen as a central aspect of updating bureaucracies.

Discussion

Given the growing recognition of the role that bureaucrats and bureaucracies play in determining state capability, it will be important for researchers to understand similarities and differences across such state organisations in order to advance the literature. Our analyses contribute to the understanding of within-country variation in effectiveness and, further, highlight the role that management plays in driving pockets of good governance within similarly structured political institutions in relatively weak states. We hope our work will be the first of many to help establish a picture of bureaucratic effectiveness in different settings and the sources of within-country heterogeneity.

Editors' note: The column is based on an IGC project.

Photo credit: Allan Leonard/flickr.

References

Bloom, N and J Van Reenen (2007), "Measuring and explaining management practices across firms and countries", Quarterly Journal of Economics 122: 1351-408.

Bloom, N, R Sadun and J Van Reenen (2012), "The organization of firms across countries", Quarterly Journal of Economics 127: 1663-705.

Finan, F, B A Olken and R Pande (2015), "The personnel economics of the state", in Handbook of Field Experiments, forthcoming.

Rasul, I and D Rogger (2016), "Management of bureaucrats and public service delivery: Evidence from the Nigerian Civil Service", Economic Journal, forthcoming.

Rasul, I, D Rogger and M Williams (2017), “Management and bureaucratic effectiveness: A scientific replication”, mimeo, UCL.

Endnotes

[1] As we use the minimum and maximum score of reports for the extensive margin of project output, it is possible that the percentage of initiated projects is below that for completed projects, as occurs in one organisation.

[2] Each index is converted into a z-score (so are continuous variables with mean zero and variance one by construction), where both are increasing in the commonly understood notion of ‘better management’.