Women choose lower quality colleges, travel for a longer time, and spend more money on commuting, relative to men, to feel safer

Street harassment, or sexual harassment in public spaces, is a serious problem around the world. In Delhi, India, 95% of women aged 16-49 report feeling unsafe in public spaces (UN Women and ICRW 2013). Women incur significant psychological costs from sexual harassment (Langton and Truman 2014)and actively take precautions to avoid such confrontations (Pain 1997). However, there is limitedevidenceon the economic costs of daily harassment (Aguilar et al. 2016). Moreover, there is no quantitative evidence of the effect harassment has on women’s human capital attainment.

The study: Does sexual harassment hinder education?

One potential cost of living in an environment where street harassment is prevalent is that women may avoid opportunities that would otherwise be available to them. At Delhi University (DU), for example, women tend to attend lower quality colleges than men, even though on average they do as well or better than men in thenational high school exams.

In Borker (2018), I ask whether women choose to attend lower quality colleges to avoid sexual harassment while travelling to and from college. I answer this question in a context where 71% of the enrolled students live at home with their families and travel to college every day, mostly by public transport.

The stats: Sexual harassment of female students in Delhi

- Over 89% have faced some form of harassment while traveling in the city.

- 63% of female students have experienced unwanted staring.

- 50% have received inappropriate comments.

- 40% have been touched, groped, or grabbed.

- 26% have been followed.

The methodology: Estimating the willingness to pay for higher perceived safety of travel routes at a commuter university

To assess if women are choosing a low-quality college because it is located on a ‘safe’ route, using a model of college choice I evaluate the difference in female and male students’ willingness to pay for travel safety in terms of:

- college quality,

- travel costs, and

- travel time.

The difference captures the cost of street harassment for women, since men in Delhi do not face such harassment but are expected to have similar concerns about other forms of safety.

I exploit the ideal set-up of Delhi University (DU) and assemble a unique dataset. DU is composed of 77 colleges that are spread across Delhi. The colleges vary in quality, with each college having its own campus, classes, staff, and placements. Admissions in DU are strictly based on students' high school exam scores. My analysis consists of three stages:

- I infer students' comprehensive choice set of collegesusing detailed information on 4,000 students from a survey that I conducted at DU.

- Using the mapping capabilities of Google Maps and an algorithm that I developed, I map students' travel routes by travel mode, including both the reported travel route and the potential routes available to students for every college in their choice set.

- I then combine the information on travel routes with crowd-sourced safety data from two mobile applications: The first mobile application, SafetiPin, provides perceived spatial safety data in the form of safety audits conducted at various locations across Delhi. The second mobile application, Safecity, provides analytical data on harassment rates by travel mode. Together, the route and safety data allow me to assign a safety score to each travel route.

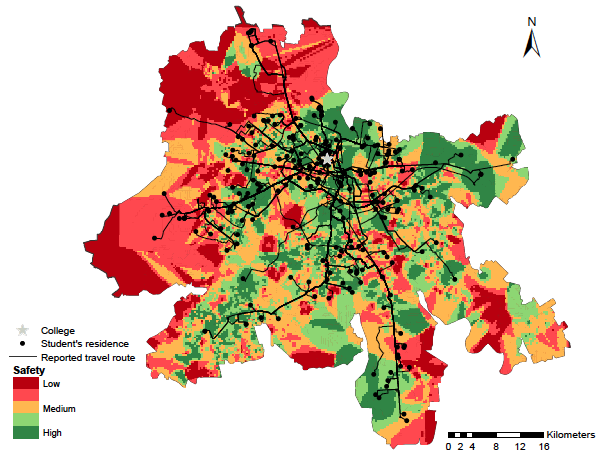

Figure 1 shows the safety data and the reported travel routes for students of one college in my sample.

Figure 1 Perceived safety and students’ reported travel routes to a college in Delhi University

To estimate the magnitude of the students' willingness to pay for travel safety, I use a combination of structural econometric methods. The analysis uses spatial variation in students’ location, destination colleges, route choices, mode choice, and area safety.

Findings: Women are willing to give up time, money, and college quality to feel safer

I find that women’s college choice can be explained in part by their concerns about exposure to street harassment.

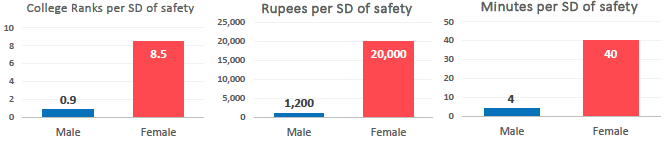

- College quality. I find that women are willing to choose a college that is in the bottom half of the quality distribution over a college in the top 20% for a route that is perceived to be safer, by one standard deviation (SD). Men on the other hand are only willing to go from a top 20% college, to a top 25% college for the same increase in (one SD) perceived travel safety. To help put this into perspective, I use district-level data on rape from the Indian National Crime Records Bureau. A SD of perceived safety while walking is equivalent to a 3.1% decrease in the rapes reported annually.

- Money. Using the travel cost method, I find that women are willing to spend INR 18,800 (USD 290) more per year than men for a route that is perceived to be one SD safer (see Figure 2). This is a significant sum of money, double the average annual tuition at DU and 6.7% of the average annual per capita income in Delhi.

- Time. Women are willing to travel an additional 40 minutes daily for a route that is perceived to be one SD safer. Men are only willing to increase their travel time by four minutes for an additional SD of safety.

Figure 2 Women and men’s willingness to pay for travel safety

Implications

Using estimates from Sekhri (2014), I estimate that women's willingness to pay for safety translates into a 20% decline in the present discounted value of their post-college salaries. The findings speak to the long-term consequences of everyday harassment – perpetuating gender inequality in both education and lifetime earnings.

While my paper focuses on the effects of street harassment on women's choice of college, these findings are relevant for other economic decisions made by women as well. For instance, the propensity to avoid street harassment could impact women’s employment decisions and in part explain India’s low levels of female labour force participation.

Policy evaluations and recommendations

I also evaluate and interpret the impact of different existing and potential interventions that could alleviate the impact of street harassment on the economic choices of women. I find that the first-best policy of making all travel routes safe for women reduces the college rank gap between men and women by 5%. While it is the ultimate hope, such an ambitious policy is hard to design and implement in the short or even medium term.

An alternative approach could be to design programmes that improve women's preferences for safety through empowerment. These programmes can take many different forms, for example:

- Self-defence training initiatives such as SheFighter in Egypt.

- Encouraging women to reclaim public spaces, as in the WalkAlone campaign by Blank Noise in India

- Information campaigns like ‘Stop Telling Women to Smile’ in several cities across the world.

My analysis shows that affecting women’s safety preferences has the same effect on closing the gender gap in higher education as the first-best policy, and it is more effective than subsidising travel by safer modes. This suggests that programmes that empower women are one of the most effective and sustainable approaches to reducing the costs of street harassment.

References

Aguilar, A, Gutierrez, E and Soto, P (2016), "Women-only Subway Cars, Sexual Harassment, and Physical Violence: Evidence from Mexico City", Working Paper.

Borker, G (2018), "Safety First: Perceived Risk of Street Harassment and Education Choices of Women", Working Paper.

Langton, L and Truman, J L (2014), "Socio-emotional impact of violent crime", US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Pain, R H (1997), “Social geographies of women’s fear of crime”, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 22(2): 231–244.

Sekhri, S (2014), "Prestige Matters: Value of Connections Formed in Elite Colleges", Working Paper. Accessible:

UN Women and ICRW (2013), Unsafe: An Epidemic of Sexual Violence in Delhi’s Public Spaces: Baseline Findings from the Safe Cities Delhi Program, International Center for Research on Women (ICRW).