Evidence from Nigeria suggests that TV shows can promote safer sexual practices mainly through learning, rather than social conformity

This column is part of a series on the role of media in economic development*

Understanding how and why people change their attitudes, and consequently their behaviour, is a key challenge for development interventions. Behaviour change campaigns have shown limited effectiveness in developing countries, which presents a pressing challenge in the context of HIV prevention. For example, Padian et al. (2010) found that only one in seven HIV campaigns were effective.

Edutainment

Researchers have turned their attention to alternative approaches to inspiring behavioural change, one of which is ‘edutainment’ (short for entertainment education). Edutainment is the purposeful use of mass media programming to achieve development objectives through changing behaviour and attitudes of audiences and other community members.

This is an emerging field in development (World Bank 2015) and the evidence base is nascent and mostly correlational, however rigorous evaluations are emerging (see DellaVigna and La Ferrara 2015 for a review). Experimental studies on edutainment interventions have shown positive impacts on financial literacy (Coville et al 2015, Berg and Zia 2017), health (Banerjee et al. 2015, Kearney and Levine 2015), political participation (Mvukiyehe 2017), and conflict resolution (Paluck and Green 2009) .

There are two gaps, however:

- There is limited evidence about the mechanisms or channels through which edutainment works.

- There is no evidence on the spilloverson sexual behaviours, as these are private behaviours that tend to be discussed behind closed doors.

In our forthcoming paper (Banerjee et al, forthcoming), we address both these gaps.

The experiment: Sex in (Lagos) City

Our experiment studied the effectiveness of the third season of the edutainment TV drama, MTV Shuga. The TV series is broadcast across sub-Saharan Africa with the aim to promote safer sexual practices among youth.

Methodology

For identification, we randomly selected 80 community screening locations (n=4,986). We then randomly chose 54 of these locations to show Shuga (treatment), and 26 locations to show a placebo TV drama that lacked HIV-related content (control). We decided to have a placebo rather than a control so that our results showed the effectiveness of the TV drama and did not include the effects of the delivery mechanism – community screening. The screenings lasted three hours.

The study’s population involved 18-25 year olds living in urban and peri-urban areas of southern Nigeria. Data collection included baseline and eight-month follow up surveys. To address social desirability bias (the tendency of survey respondents to answer questions in a manner that will be viewed favourably by others), two weeks after the follow up survey we conducted health camps that helped collect objective data for condom demand, HIV testing and Chlamydia infections.

Learning versus social conformity

Our study was designed to measure two potential channels for change that are central to most human behaviour models (e.g. Fishbein and Ajzen 2010): learning and social conformity.

A. Learning

Learning through information-provision in edutainment works by increasing an individual’s potential exposure to information as it is easier for some to watch a fun drama than to sit through an HIV sensitisation session. This format may also reduce resistance to top-down advice or counter-arguing. To capture this learning channel, in half of the treatment locations we only screened Shuga (T1).

B. Social conformity

The second channel, social conformity, requires information about the social norm and would not exist in the absence of the need to conform. If conformity is a key mechanism, then coordinating a shift in beliefs across the relevant peer groupis rendered an important part of the design of effective behaviour change campaigns. To identify social conformity effects, we experimented with two notions of reference groups:

1. In the other half of treatment locations (T2), after the Shuga screenings we showed videoclips containing interviews of peers of similar ages and backgrounds and ‘smart graphs’ with statistics about their attitudes after watching Shuga (see Figure 1).

We expected individuals’ views to converge towards these reference points. In our example, for the effect to be positive (negative), respondents at baseline believed that less (more) than two thirds of youth would tell their partners about their HIV+ status.

2. Second, in both treatment arms, half of respondents invited to watch Shuga (T3) were given extra tickets to bring up two friends. Unlike T2, the reference group was now chosen by the respondents themselves, so we are sure it is composed by a network of people that respondents cared about.

We hypothesised that conformist individuals should be more confident in changing their HIV attitudes and behaviours if they saw their local peers (T2) or friends (T3) being exposed to Shuga. Unlike Paluck and Green (2009), who studied the impacts of edutainment on social norms, we studied the extent to which conformity effects may ultimately influence behaviours.

Figure 1 Example of a smart graph presented in T2 videoclips

C. Spillovers

Finally, we measured programme spillovers on friends that were not directly or indirectly invited to the Shuga community screenings (T4). We asked baseline respondents to name two friends they regularly spoke with and we randomly surveyed one from the pair.

Results

Our baseline indicates no observable difference between our treatment and control groups at baseline. The preliminary results were previously discussed here and here. After eight months, Shuga had statistically significant effects on:

- indices of knowledge about HIV transmission (0.13 standard deviations) and

- attitudes towards HIV+ people (0.08 SD).

Most importantly, it increased safer sexual practices:

- The treatment group was three percentage points more likely to get tested for HIV (objective measure), which correspondents to a 100% increase over the control mean.

- The acceptability and reported incidence of concurrent sexual partnerships significantly decreased as well.

- Interestingly, the show did not induce greater condom use.

- Despite the lack of effect on condoms use, and consistent with the reduction in the number of concurrent partners (and possibly with a more general shift away from risky behaviours), the show reduced the incidence of sexually transmitted diseases.

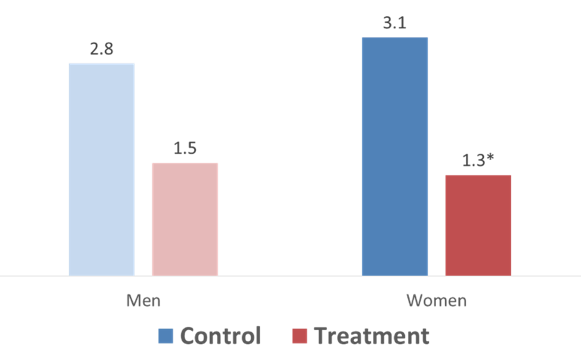

- As seen in Figure 2, the likelihood of testing positive for chlamydia among our female sample decreased by 55%(1.3% versus 3.1% in the control group). For the male sample, the reduction was not statistically significant.

Figure 2 Tested positive for chlamydia

Mechanisms and spillovers

1. Learning rather than social conformity appears to drive results

We first tested if our main treatment effects differed by how likely someone was to conform. Using an overall conformity measure, based on questions related to conformity, attachment to tradition and self-direction collected at baseline (Schwartz 2012), we find no evidence of differential effects. Moreover, we found no effects for both conformity experimental arms. This implies that:

- there is no evidence that exposing individuals to the views of local peers (T2) had stronger effects than simply watching Shuga (T1),

- there is no evidence that respondents’ beliefs converged to the norm announced in the T2 videoclips, and

- watching Shuga with a friend (T3) had no differential effects.

2. Information spillovers

- We observe significant effects on untreated friends’ knowledge about HIV transmission, suggesting people who watched Shuga conveyed its messages to their friends.

- The spillover effect is driven by friends of the opposite sex, possibly proxying for respondents’ boyfriends or girlfriends.

- We see no significant effects on untreated friends’ attitudes and behaviours, however, suggesting that direct exposure to the show may be needed to trigger change at a deeper level.

Implications

Our results indicate that this TV show positively changed deep-seated views and behaviours in the context of HIV-related outcomes. Our results also suggest that the value added of edutainment comes from its ability to deliver information that is very difficult to convey through traditional formats. The spillover effects on knowledge but not on attitudes and behaviours of untreated friends suggests the need to ‘live the experience’ of edutainment.

While our findings do not suggest that social effects are unimportant, they do highlight the complexities of their role for this private behaviour. More research is needed to assess the potential role of conformity when manipulation can be induced in larger and naturally occurring sets of peer groups (e.g. classrooms, schools or villages), as well as in the context of online social networks. Given the ability to reach large-scale audiences at low marginal costs, future research that helps maximise the impact of edutainment should have large-scale development payoffs.

*Note from the Editor-in-Chief: Over this week, at VoxDev, we decided to tackle the broader question of the role of media in economic development. All three articles this week are linked through this common theme. We opted for this theme given the recent work on the role of the media, and social media in particular, in the developed world (for example, The spread of true and false news onlineand Economic and Social Impacts of the Media), all amidst the Cambridge Analytica scandal. Clearly, media and social media are extremely persuasive and have important effects in the developed world. We decided it was high time to build a series around similar issues in the developing world – so here it is. Enjoy!

References

Banerjee, A, Barnhardt, S and Duflo, E. Movies (2015), “Margins and Marketing: Encouraging the Adoption of Iron-Fortified Salt”, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper Series 21616.

Banerjee, A, La Ferrara, E and Orozco, V (forthcoming) “The Entertaining Way to Behavioral Change”, forthcoming World Bank Working Paper 2018

Berg, G and Zia, B (2017), “Harnessing Emotional Connections to Improve Financial Decisions: Evaluating the Impact of Financial Education in Mainstream Media”, Journal of the European Economic Association 15(5): 1025–1055.

Coville, A, Unsch, F, Di Maro, V and Zottel, S (2015), "The impact of Financial Literacy through Feature Films: Evidence from a Randomized Controlled Trial in Nigeria", Financial literacy and Education, World Bank conference paper.

DellaVigna, S and La Ferrara, E (2015), “Economic and Social Impact of the Media”, in Handbook of Media Economics, Volume 1, pp. 723-768.

Fishbein, M and Ajzen, I (2010), Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach, New York: Psychology Press (Taylor & Francis).

Kearney, M S and Levine, P B (2015), "Media Influences on Social Outcomes: The Impact of MTV's 16 and Pregnant on Teen Childbearing", American Economic Review 105(12): 3597-3632.

Mvukiyehe, E (2017), "Can media interventions reduce gender gaps in political participation after civil war? evidence from a field experiment in rural Liberia" (English), Policy Research working paper; no. WPS 7942; Impact Evaluation series.

Padian, N, McCoy, S, Balkus, J and Wasserheit, J (2010), "Weighing the gold in the gold standard: challenges in HIV prevention research", AIDS 24(5): 621-35.

Paluck, E and Green, D P (2009), “Deference, dissent, and dispute resolution: An experimental intervention using mass media to change norms and behavior in Rwanda”, American Political Science Review 103(4).

Schwartz, S H (2012), “An Overview of the Schwartz Theory of Basic Values”, Online Readings in Psychology and Culture 2(1): 1-20.:

World Bank (2015), World Development Report: Mind, Society and Behavior, Washington, DC.