A digital mobile-deposit service reduced deposit transaction costs but did not increase savings

Evidence shows that increasing formal savings improves the standard of living in low-income communities along a number of dimensions, from increasing business investments (Dupas and Robinson, 2013), to health and education (Prina, 2015), income (Schaner, 2016), and labour supply (Callen et al. 2014). But such financial inclusion remains elusive for many of the world’s poor – 65% and 35% of people in low- and middle-income countries, respectively, do not have an account with a financial institution.1

One potential explanation is high transaction costs. The small size of typical saving deposits from the working poor, and the time and pecuniary costs of travelling to a bank, may make regular use of formal savings accounts impractical. If high deposit transaction costs are an important constraint, digital financial products may help increase savings and financial access by reducing these transaction costs.

This potential has led to the commitment of significant resources and political will to increase the reach of mobile-linked services. For example, “the research of low-cost digital financial services” is a component of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation’s strategy to address financial inclusion. Relatedly, speeding up the transition to a digital economy is often used as a justification for India’s 2016 demonetisation. Despite this push, progress in building products that link mobile money to conventional interest-bearing bank accounts has been slow. This raises questions about the demand for mobile-linked saving products and whether such products can increase saving mobilisation.

The study and behavioural mechanism

In a new study in Sri Lanka, we shed light on these questions by estimating the effect of offering a mobile-linked deposit service (de Mel et al. 2020). This service allowed people to make deposits into a bank account through their mobile phone, using the same scratch-card method they normally use to add airtime minutes to their phone. While the service allowed for mobile deposits, withdrawals from the account would require a trip to the bank. This mirrors the typical structure of mobile money and mobile saving products, in which deposits are free but withdrawal costs generally are higher.

This focus on reducing deposit transaction costs is based on the idea that most people make deposits more often than withdrawals. Making withdrawals costly may even have a behavioural benefit of increasing savings. If deposit transaction costs are a key barrier to savings, then mobile-linked accounts should increase formal savings.

The data

To estimate the demand for, and impact of, the mobile-linked deposit service, the service was offered for free or for a fee to a random subset of individuals deemed likely to benefit from reduced deposit transaction costs. To ensure that other barriers did not prevent use of the service, these individuals were also provided with a mobile phone and SIM card, assistance in opening the bank account, and personalised demonstrations of using the service.

We then conducted high frequency household surveys to examine how the service’s availability impacted household savings, consumption, and labour earnings. The study leveraged a large sample of individuals and used random assignment to discern the causal impact of offering the mobile-deposit service.

The results

We find that the majority of individuals did not use the service after the initial demonstration. Even among those who were provided with the service for free, only 26% made even one deposit through the service and only 7% made ten or more deposits over the course of the year. Most of those who tried the service once did not continue to use it. Usage was no greater among those more comfortable with mobile phones, the more educated, or those with more trust in the service. Several other studies that evaluate the impact of innovations reducing transaction costs have also found relatively modest adoption rates (e.g. Dupas et al. 2018, Flory 2011, Ashraf et al. 2006).

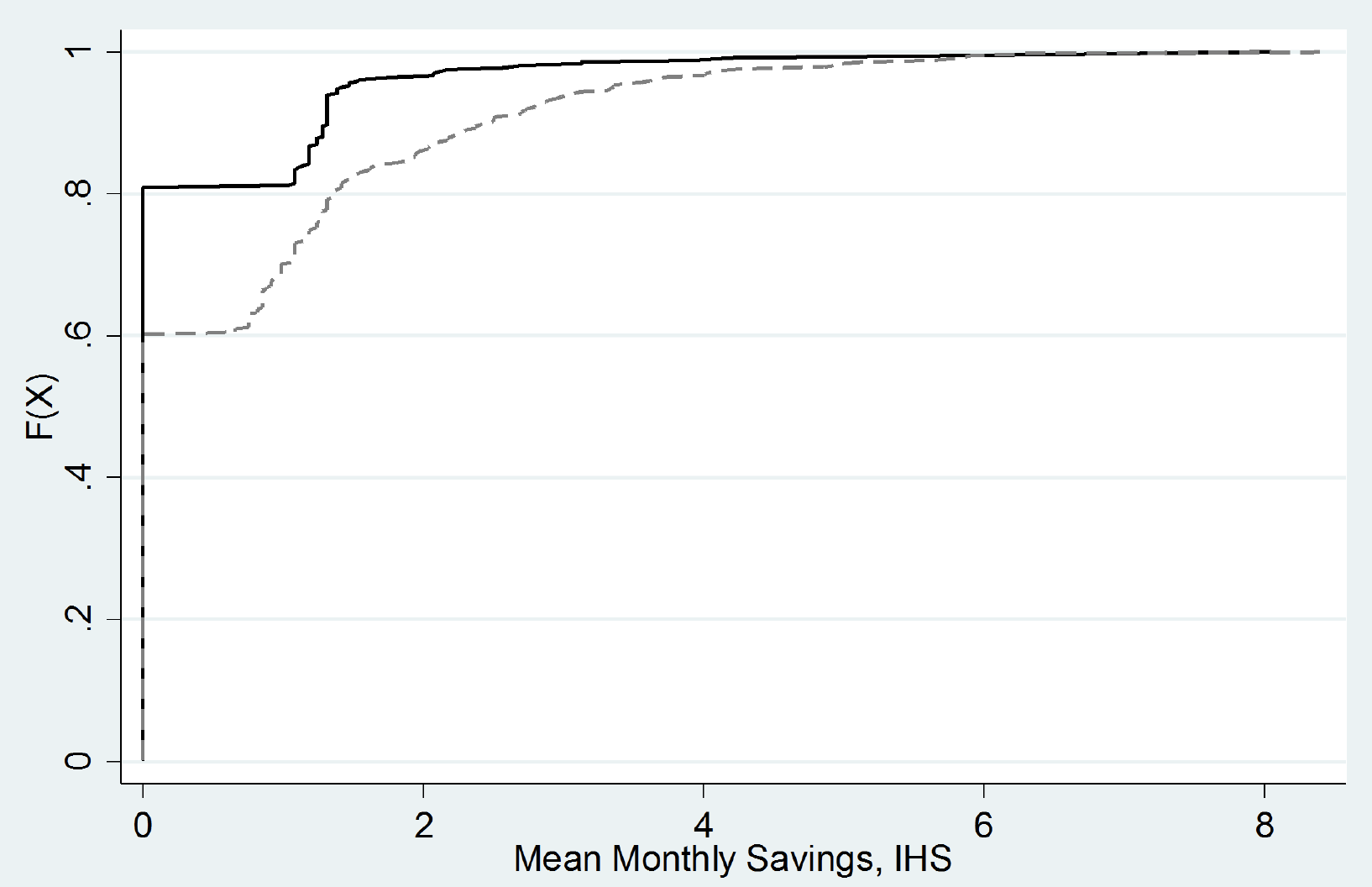

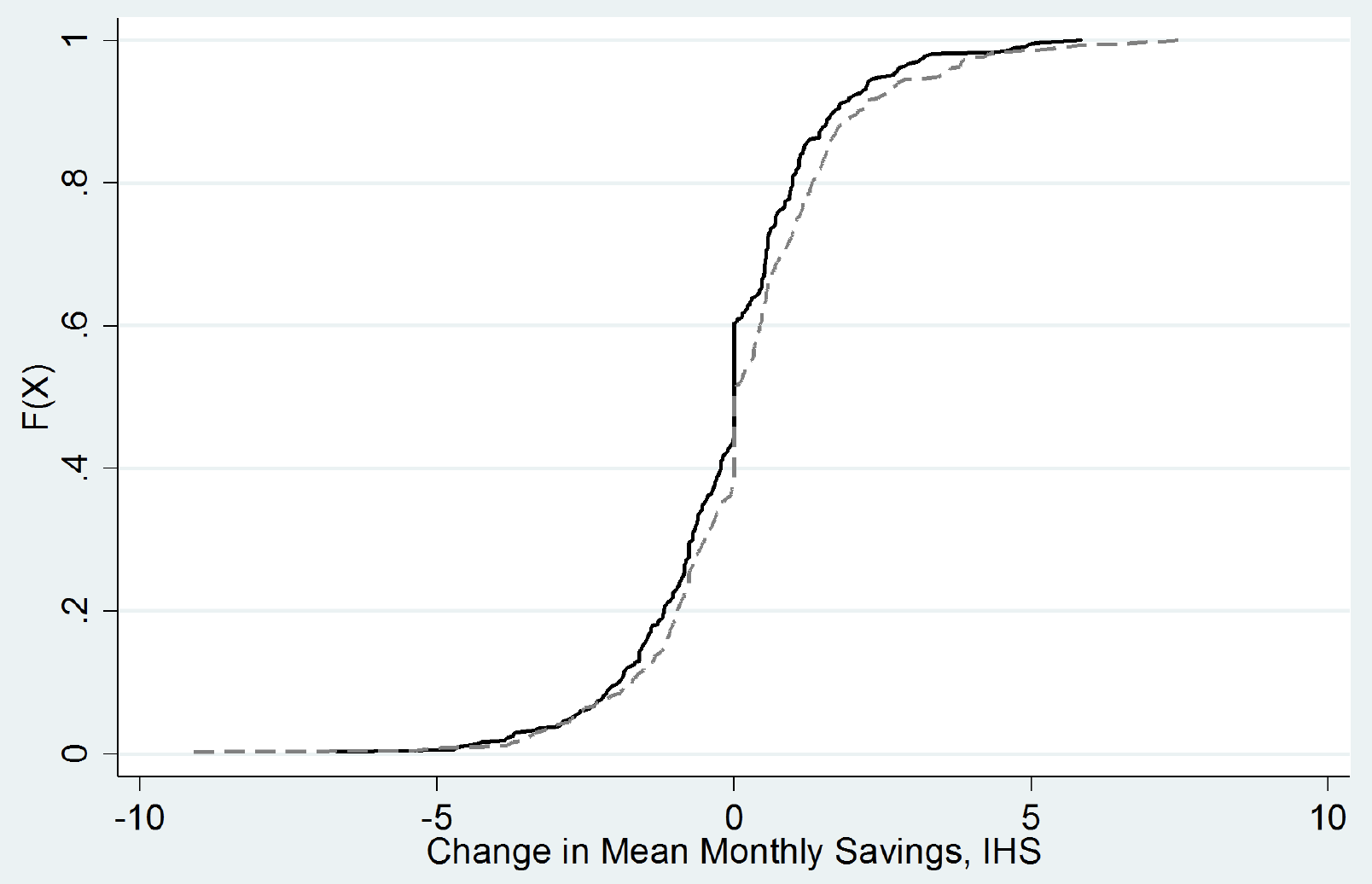

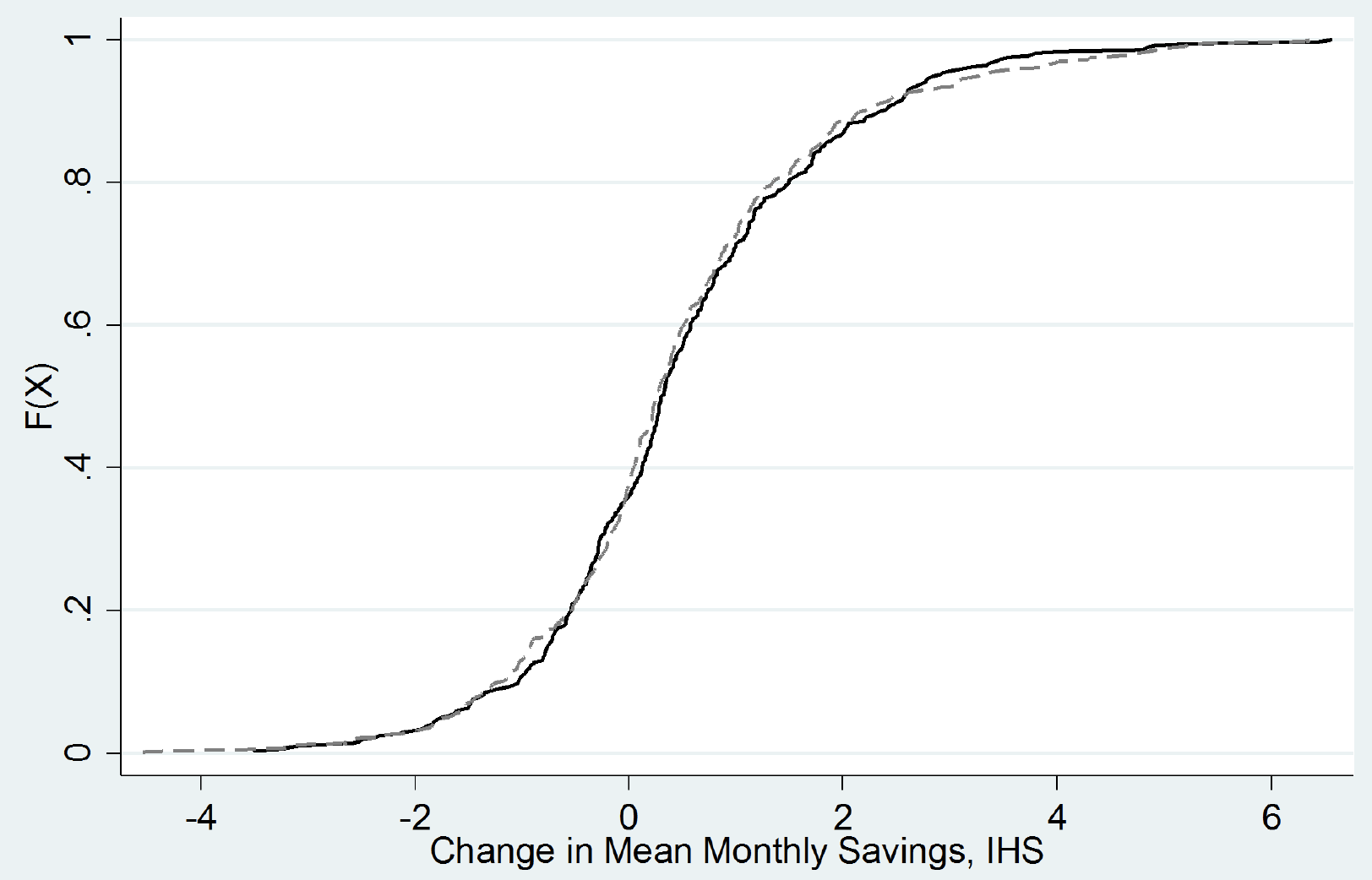

In addition to low use, offering the service also had minimal effects on savings behaviour. Figures 1a and 1b show that offering the service did lead to an increase in savings deposits with the partner bank, including a 29% increase in savings deposits in the formal banking sector more generally. But there was no increase in total household savings (Figure 1c). In addition, the amounts deposited into formal savings, even with the partner bank, do not represent meaningfully large increases, and many of the deposits were made in person rather than through the mobile-deposit service. This suggests that once the account was opened, many were willing to incur the in-person deposit transaction costs despite having the option to use the mobile-deposit service for free. Given the low use and impact on savings, it makes sense that the price charged for the service did not generally matter.

Figure 1 Cumulative density function (CDF) of mean monthly saving deposits

a) Mean monthly partner deposits

b) Change in mean monthly formal deposits

c) Change in mean monthly total deposits

Note: Control = solid line, treatment = dashed line.

Policy implications

Our findings suggest that deposit transaction costs are unlikely to be the major inhibitor of formal savings in Sri Lanka. Though heterogeneity analysis suggests that some individuals may have benefitted from the service (in particular, women and those living somewhat distantly from a bank), on average the service was not transformational in increasing savings. The modest results are similar to those found by others studying the effect of mobile-linked savings in areas where mobile money is more popular (Batista and Vicente 2016, Batista and Vicente 2017, Bastian et al. 2018).

The results support a growing consensus in the literature that deposit transaction costs may determine where a person saves, but not how much a person saves. This literature suggests two possible explanations that warrant further attention:

- Behavioural constraints: Many interventions that successfully increase savings by lowering deposit transaction also reduce behavioural constraints in the process, suggesting that behavioural constraints may be driving the effect on increased savings.

- Withdrawal transaction costs: Most interventions that reduce deposit transaction costs continue to have withdrawal transaction costs. It remains an open question whether withdrawal transaction costs are inhibiting the success of reduced transaction costs, and whether digital products that reduce withdrawal costs may be more successful in delivering on the promise of digital financial services.

References

Ashraf, N, D Karlan and W Yin (2006), “Deposit Collectors”, The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy 5(2): 1–24.

Bastian, G, I Bianchi, M Goldstein, and J Montalvao (2018), “Improving Access to Savings Through Mobile Money, with and without Business Training: Experimental Evidence from Tanzania”, Working Paper.

Batista, C, and P Vincente (2016), “Introducing Mobile Money in Rural Mozambique: Evidence from a Randomized Field Experiment”, Working Paper.

Batista, C, and P Vicente (2017), “Improving Access to Savings Through Mo-bile Money: Experimental Evidence from Smallholder Farmers in Mozambique”, Working Paper.

Callen, M, S de Mel, C McIntosh, and C Woodruff (2019), “What are the headwaters of formal savings? Experimental evidence from Sri Lanka”, Review of Economic Studies 86(6): 2491–2529.

de Mel, S, C McIntosh, K Sheth, and CWoodruff (2020), “Can Mobile-Linked Bank Accounts Bolster Savings? Evidence from a Randomized Controlled Trial in Sri Lanka”, The Review of Economics and Statistics, forthcoming.

Dupas, P, and J Robinson (2013), “Savings Constraints and Microenterprise Development: Evidence from a Field Experiment in Kenya”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 5(1): 163–92.

Dupas, P, D Karlan, J Robinson, and D Ubfal (2018), “Banking the Unbanked? Evidence from Three Countries”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 10(2): 257–97.

Flory, J A (2011), “Micro-Savings and Informal Insurance in Villages: How Financial Deepening Affects Safety Nets of the Poor, A Natural Field Experiment.” Working Paper s2011-008, Becker Friendman Institute for Research in Economics.

Prina, S (2015), “Banking the poor via savings accounts: Evidence from a field experiment”, Journal of Development Economics 115: 16–31.

Schaner, S (2016), “The Cost of Convenience? Transaction Costs, Bargaining Power, and Savings Account Use in Kenya”, Journal of Human Resources 52(4): 919–945.

Endnotes

1 Source: https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/global-financial-inclusion-global-findex-database. The percentage refers to people aged 15 or older who have also not used a mobile money service.