Face-to-face interactions between teachers and their coaches might yield better results in teacher training than more high-tech, virtual approaches

Developing countries are often characterised by low levels of student learning, large class sizes, and weak content knowledge and pedagogical practice among teachers (Bold et al. 2017). All of these challenges are further exacerbated in times of prolonged school closures. There is thus an urgent need to find scalable models to upgrade teachers’ pedagogical skills in these countries during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The good news is that we are gathering robust evidence on what works. Structured pedagogical programmes that provide teachers with teaching material and continuous coaching support have been found to be hugely successful in multiple contexts (Piper et al. 2018, Cilliers et al. 2020a, Eble et al. 2021). The bad news, however, is that these programmes are usually too expensive for governments to implement, and even small changes in their design can reduce their effectiveness (Kerwin and Thornton 2018).

One way to provide coaching at scale and at a lower cost is to rely on virtual coaches. In fact, a small number of studies in the United States have found virtual coaching to be as effective as in-person coaching. But there are many reasons why virtual coaching might not work. For instance, teachers might struggle with adopting to new technology, and face-to-face contact can be key in building a relationship of accountability and trust between the teacher and the coach.

Direct comparison between virtual and on-site coaching

In a recent study (Cillers et al 2020b), we collaborated with South Africa's Department of Basic Education to evaluate two teacher professional development programmes aimed at improving teaching of early-grade English as a second language (ESL). In both programmes, teachers received the same lesson plans, learning materials, and training at the beginning of the year. The programmes differed in the following key dimensions:

- In the on-site coaching programme, teachers received in-classroom visits by coaches and paper lesson plans.

- In the virtual coaching programme, teachers interacted with the coach through regular phone calls, text messages, and WhatsApp groups. The lesson plans were delivered on an electronic tablet, which also included pre-recorded pedagogical videos.

Both programmes were implemented over a period of three years, targeting grade one teachers the first year, grade two teachers in the second, and grade three teachers in the third year. We tracked an incoming cohort of grade one students and followed them over a period of three years, assessing the students and conducting teacher interviews and document inspections at the end of each year. In the final year, we also performed classroom observations.

Sobering results on reading proficiency

After one year, both the virtual and on-site coaching programmes improved students’ oral language skills by 0.55 and 0.52 standard deviations, respectively. Neither programme improved English reading skills, but this is not surprising since the focus of grade one ESL curriculum is on vocabulary and not reading skills. One would expect literacy improvements in the second and third years, when the curriculum focuses on developing reading skills.

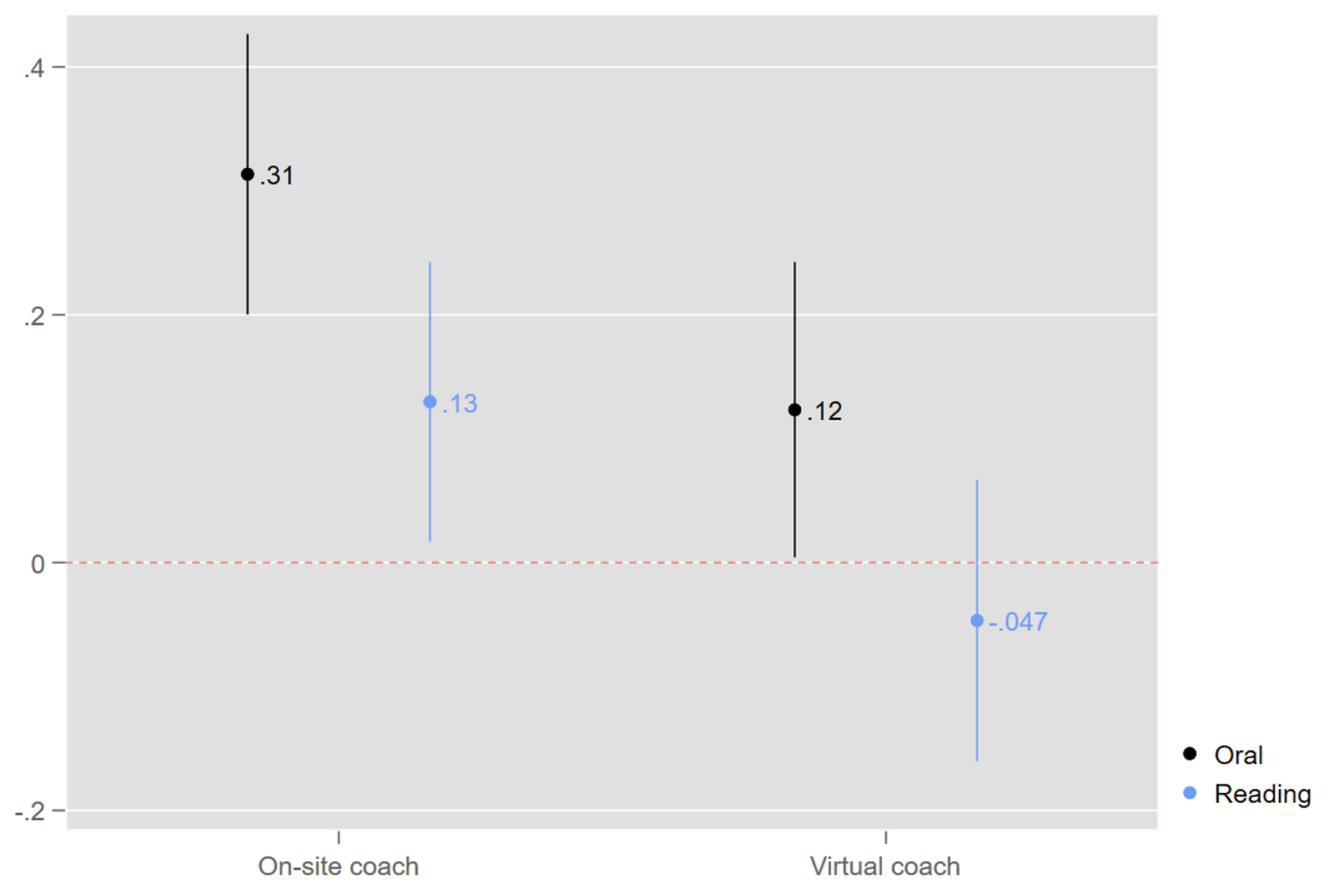

However, we found that after three years, the virtual coaching programme had no positive impact on reading skills, whereas the on-site programme did (by 0.13 standard deviations). Moreover, the on-site coaching programme was now more than twice as effective at improving oral language skills (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Treatment effects on English oral language and reading proficiency after three years

Note: Impacts are in standard deviations

The most likely reason for these divergent trends is that the on-site coaching programme is more effective at improving the more difficult pedagogical skills required for teaching reading. Classroom observations show that students whose teachers received on-site coaching support were more than twice as likely to practice reading in small groups, and almost six times more likely to receive individual feedback from a teacher. To be fair, teaching practices also improved in the virtual coaching programme, but not by much, and not for these techniques.

More concerning was the fact that the virtual coaching programme actually reduced students’ home language reading skills. We cannot say exactly why, but the crowding out of teaching time could be part of the explanation – teachers in the virtual coaching programme dedicated fewer hours to teaching home language, and were less satisfied with their ESL curriculum coverage.

Why was the virtual coaching arm less effective?

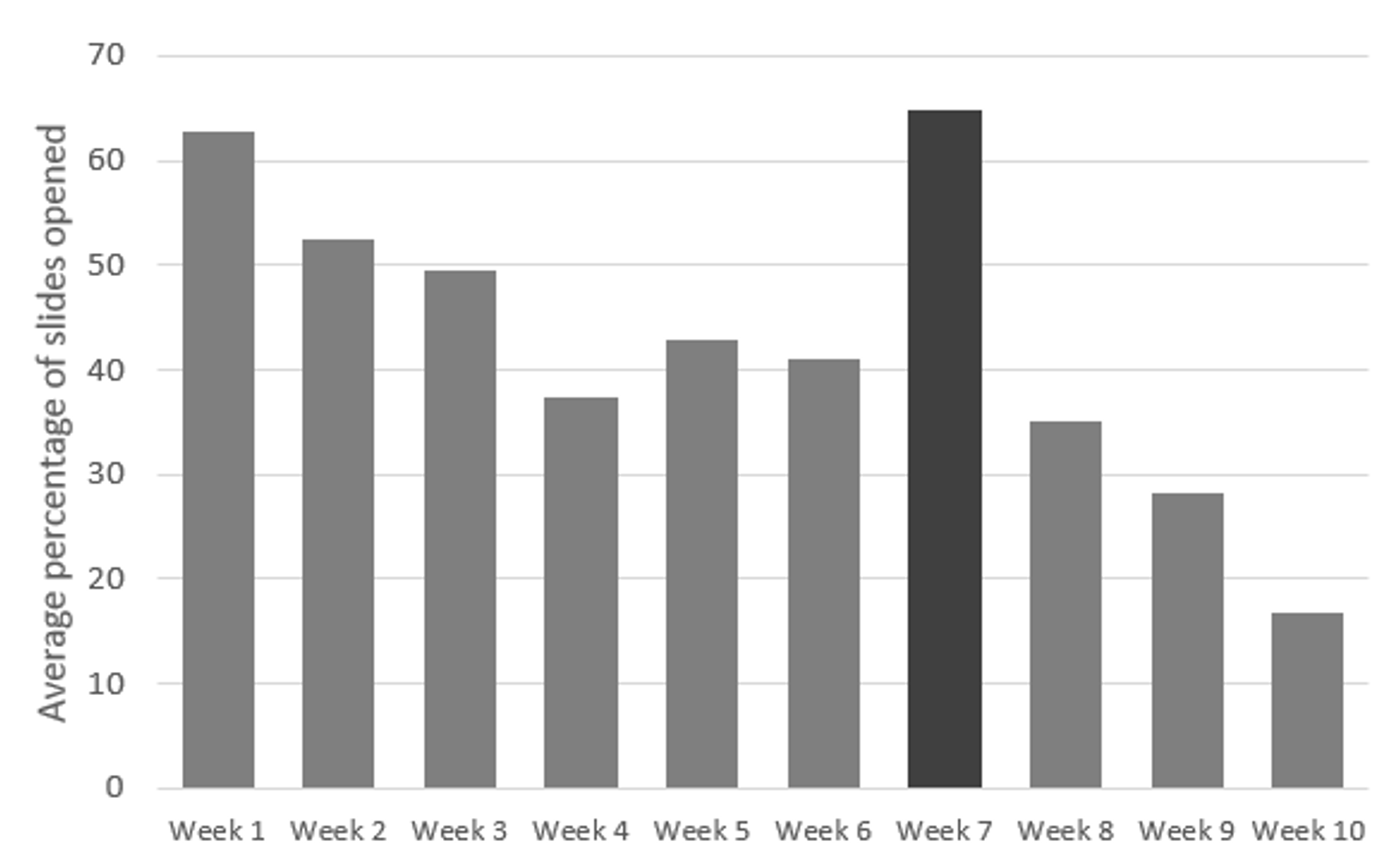

Although we cannot provide a definitive answer to this question, we can rule out some explanations. It was not due to the (1) quality of implementation (which was high for both programmes), (2) the frequency of interaction (also high), or (3) technological barriers. Almost all teachers in the virtual coaching programme used the electronic lesson plans at least once, but usage decreased over time (see Figure 2) and was highest in the week when student assessments took place.

Figure 2 Proportion of teachers who opened a lesson plan on their tablet, by week

Note: Standardised student assessment took place in week 7.

This suggests that in-person contact was a key ingredient in the success of the on-site coaching programme, relative to the virtual programme. We posit three potential mechanisms enabled by in-person contact that led to this:

- On-site coaches were able to observe teaching in the classroom, which allowed for more individualised feedback.

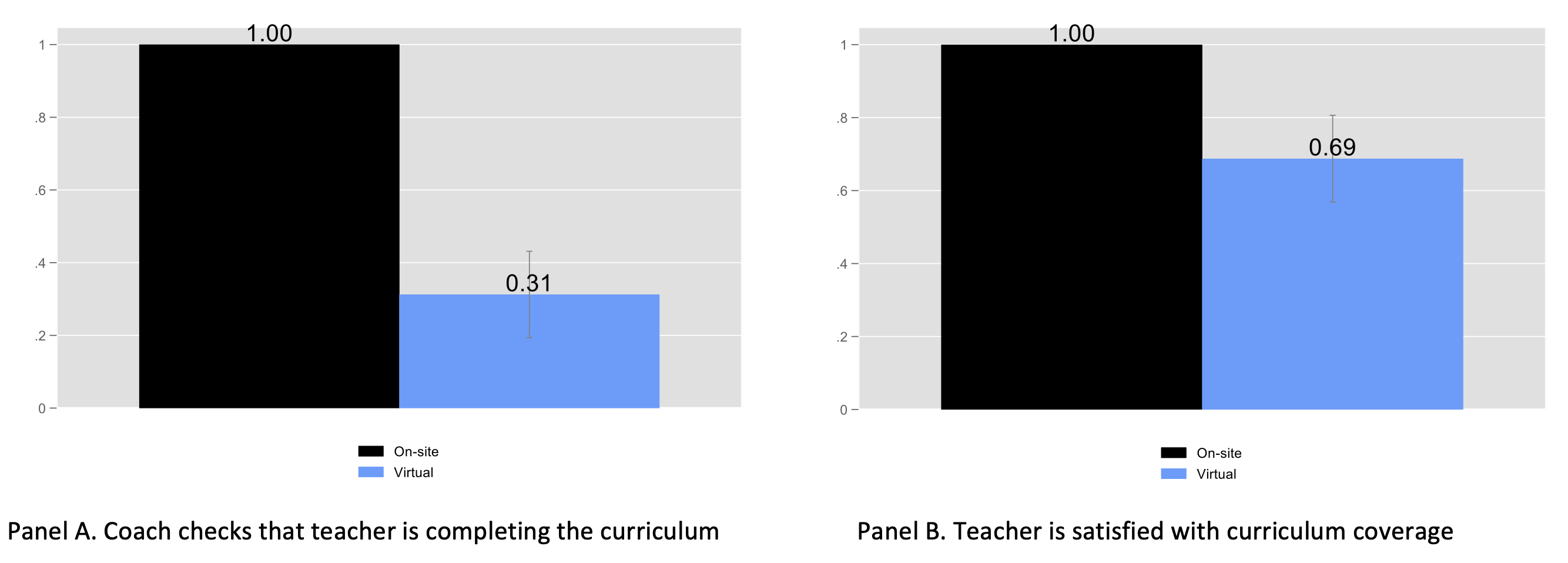

- Teachers were held more accountable by the on-site coach to complete their curricula and attempt new techniques (see Figure 3)

- Face-to-face interactions helped create a relationship of trust between teachers and coaches (this was also backed up by qualitative research)

Figure 3 Accountability and curriculum coverage

Note: Data from teacher survey conducted after classroom observations. Teachers were asked to list if someone checks their coverage of curricula.

What should policymakers do?

These results demonstrate that technology is, unfortunately, not a panacea for improving teaching quality in developing countries and the search for scalable models of high-quality teacher professional development must go on. However, these results also do not invalidate the promise of, and the need for, technology in providing high-quality professional development. In our view, there are two broad policy lessons from this study.

- Combine technology interventions with robust accountability systems. As human beings, we are continuously held accountable by the threat of monitoring from our peers. Researchers have found, for example, that just putting a picture of human eyes on a wall can improve generosity (Nettle et al. 2013). Interventions that rely on in-person contact therefore have a built-in accountability system that is lost when all interaction goes virtual. Technology interventions therefore need to find substitutes for this accountability mechanism.

- Allow initial face-to-face contact to help build a relationship of trust between the teacher and coach. Qualitative researchers in our study concluded that the development of a relationship of trust was key to the success of the on-site coaching programmes. Teachers were only willing to openly admit shortcomings and discuss ways to improve their teaching after they saw the coach as an ally. Perhaps such a relationship can be sustained virtually once it has been developed through in-person contact.

References

Bold, T, D Filmer, G Martin, E Molina, B Stacy, C Rockmore, J Svensson and W Wane (2017), "Enrollment without learning: Teacher effort, knowledge, and skill in primary schools in Africa", Journal of Economic Perspectives 31(4): 185-204.

Cilliers, J, J Bram Fleisch, C Prinsloo and S Taylor (2020a), "How to improve teaching practice? An experimental comparison of centralized training and in-classroom coaching", Journal of Human Resources 55(3): 926-962.

Cilliers, J, J Brahm Fleisch, N M Kotzé, N Mohohlwane, S Taylor and T Thulare (2020b), "Can Virtual Replace In-person Coaching? Experimental Evidence on Teacher Professional Development and Student Learning in South Africa", Working Paper.

Eble, A, C Frost, A Camara, B Bouy, M Bah, M Sivaraman, P J Hsieh C Jayanty, T Brady, P Gawron, S Vansteelandt, P Boone, D Elbourne. "How much can we remedy very low learning levels in rural parts of low-income countries? Impact and generalizability of a multi-pronged para-teacher intervention from a cluster-randomized trial in The Gambia", Journal of Development Economics 148 (2020): 10253

Kerwin, J T and R L Thornton (2018), "Making the grade: The sensitivity of education program effectiveness to input choices and outcome measures", Review of Economics and Statistics, 1–45.

Nettle, D, Z Harper, A Kidson, R Stone, IS Penton-Voak and M Bateson (2013), "The watching eyes effect in the Dictator Game: it's not how much you give, it's being seen to give something",x Evolution and Human Behavior 34(1): 35-40.

Piper, B, SS Zuilkowski, M Dubeck, E Jepkemei and SJ King (2018), "Identifying the essential ingredients to literacy and numeracy improvement: Teacher professional development and coaching, student textbooks, and structured teachers’ guides", World Development 106, 324-336