Road connectivity leads to workers moving out of agriculture and improvements in education but no substantial effects on income, assets or consumption

In India, rural roads but no vehicles

Between 2001–2015, the Indian government spent US$40 billion building roads to bridge the two Indias – urban and rural. While conducting research on this rural road construction programme (PMGSY), we were invited by some of the programme engineers to visit some newly connected villages where they thought the programme had been particularly impactful. They brought us along five kilometres of pristine tarmac that rolled through the hills of Rajasthan to arrive at a village where, a few short years ago, the only connection to the outside world was a rugged footpath.

This being a remote village, our visit drew some attention and many residents came out to greet us. They brought out a series of cots for us to sit on while we talked to them; they set the cots down directly in the centre of the new road, unconcerned by the possibility that any vehicle traffic would be coming by. They were thrilled with the new road, they told us; and yet there was little concrete evidence of how it had changed their lives. No bus travelled on the road, nor did anyone have a vehicle that could make use of it. Even in the case of medical emergencies, residents preferred the more direct footpath to the circuitous graded road.

A fresh road, new school buildings, water pumps, phone lines, and electricity grid installations are big developments for a village. Such projects unlock considerable electoral returns for politicians. This confounds both the time and location dimensions of placement of infrastructure projects, including rural roads. If villages are doing well after they get roads, is it because the roads caused things to improve, were the roads targeted to villages that were going to improve anyway, or were the changes driven by political favouritism and a pile of other unobserved goodies?

To obtain causal evidence on how big-budget infrastructure projects transform rural economies in developing countries, creative identification strategies are needed. For some examples of causal identification projects on large-scale infrastructure works, see Lipscomb et al. (2013) and Burlig and Preonas (2021) on rural electrification, or Adukia (2017) on toilet construction in primary and secondary schools. In our research (Asher and Novosad 2020, Adukia, Asher and Novosad 2020), we assess the impact of road connectivity to villages in India.

Roads were targeted to villages exceeding sharp population thresholds

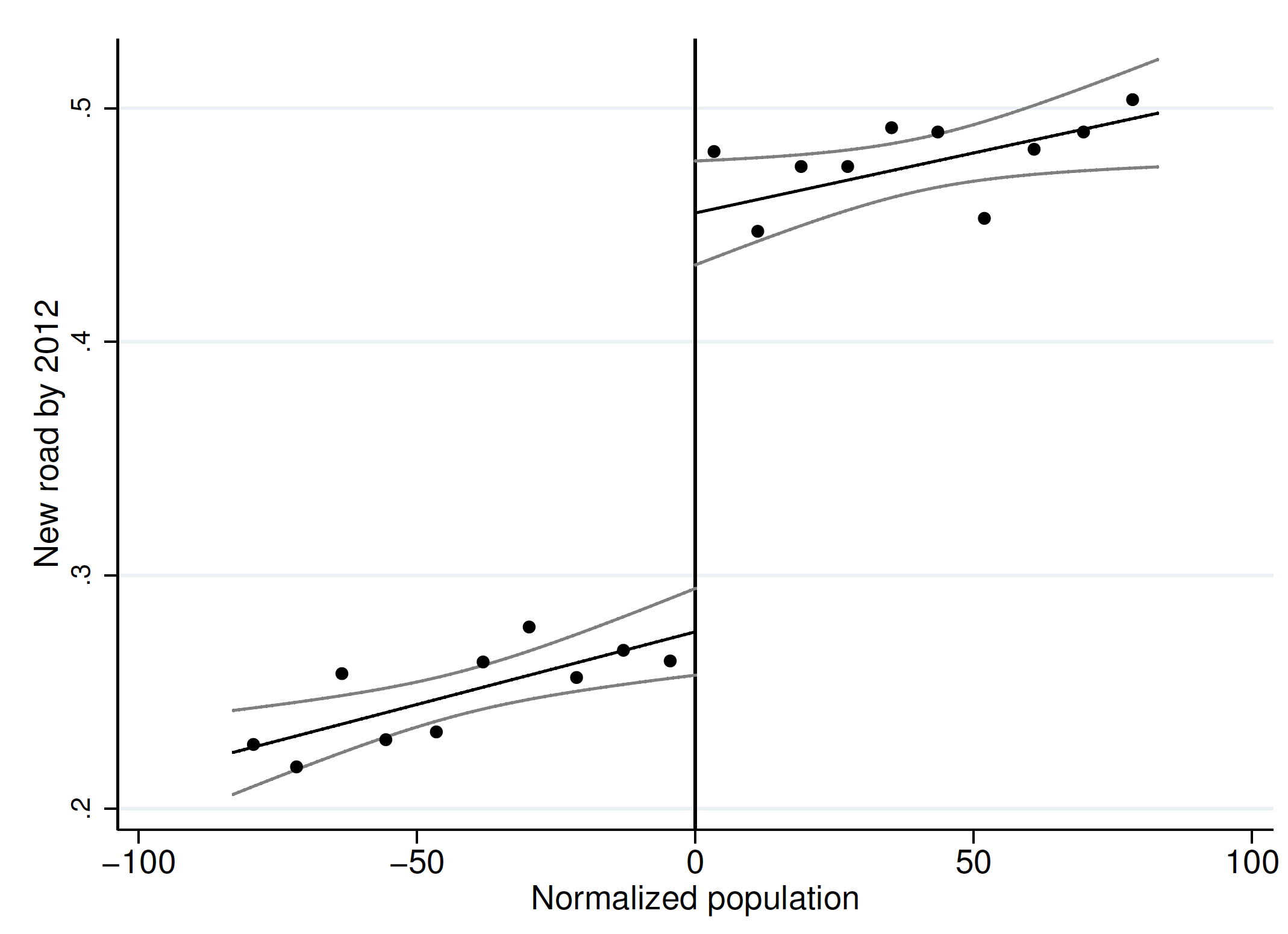

We obtained causal identification by leveraging a curious implementation rule in PMGSY: villages with populations exceeding an arbitrary threshold would have higher priority under the programme. The graph below shows that (as of 2012), villages above the population threshold were 22 percentage points more likely to get a new road than those just below the threshold. This variation allows us to use a fuzzy regression discontinuity design to estimate the causal impact of rural roads on livelihoods, incomes, and labour allocation across sectors in rural India.

Figure 1 Villages with population above the threshold were more likely to receive a road

Note: The figure plots the probability of getting a new road under PMGSY by 2012 against village population in the 2001 Population Census. Populations are standardised by subtracting the threshold population.

Roads alone fail to transform village economies, but provide access to jobs outside of villages

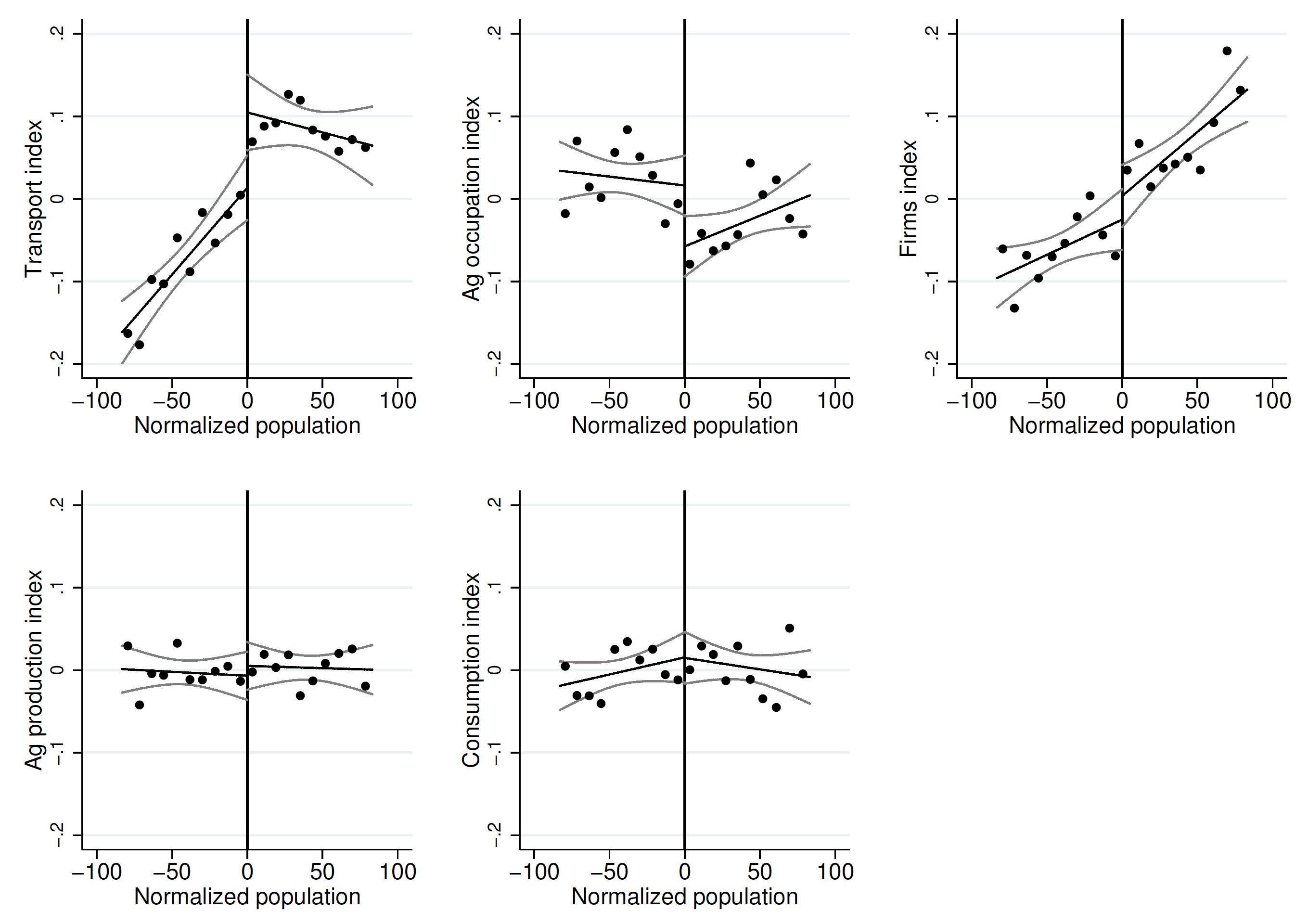

Figure 2 shows what we found. If the roads had transformational impacts, we would expect outcomes to show the same discontinuity in Figure 1, with villages just above the population thresholds being much better off. There is not much evidence of transformational impact: four years after the roads were built, we found no substantial changes in income, consumption, or assets in villages. Farmers did not increase agricultural production, shift away from subsistence crops or buy more agricultural equipment. Consistent with the lack of economic impacts, and in contrast to the effects of India’s highway network, these rural roads did not cause deforestation (Asher, Garg, and Novosad 2020).

We did find one big economic change. People were much more likely to report working outside of the agricultural sector. Since we didn’t see many new firms appearing in villages (or changes in firm-reported employment), we infer that these people must be working outside of their villages. In essence, rural roads helped people get connected to outside labour markets, where the best work opportunities lay. People seized the option to get work away from their farms as soon as it became available.

Figure 2 Rural roads moved people out of farm work, but did not affect agriculture, firm creation, or consumption in villages

Note: The figure plots the causal impact of PMGSY prioritisation on indices of major outcomes.

Access to markets improved educational outcomes, especially when schooling held promise for the future

If a road changes the set of opportunities that people see in the future, they might make different investments in their children. We used administrative data from the Unified District Information System for Education (U-DISE), which describes the universe of school enrollment across India. Because these data were available in time series, we were able to supplement the regression discontinuity analysis described above with a difference-in-differences design that examined whether school enrollments started to change in the years after a road was built (Adukia, Asher, and Novosad 2020).

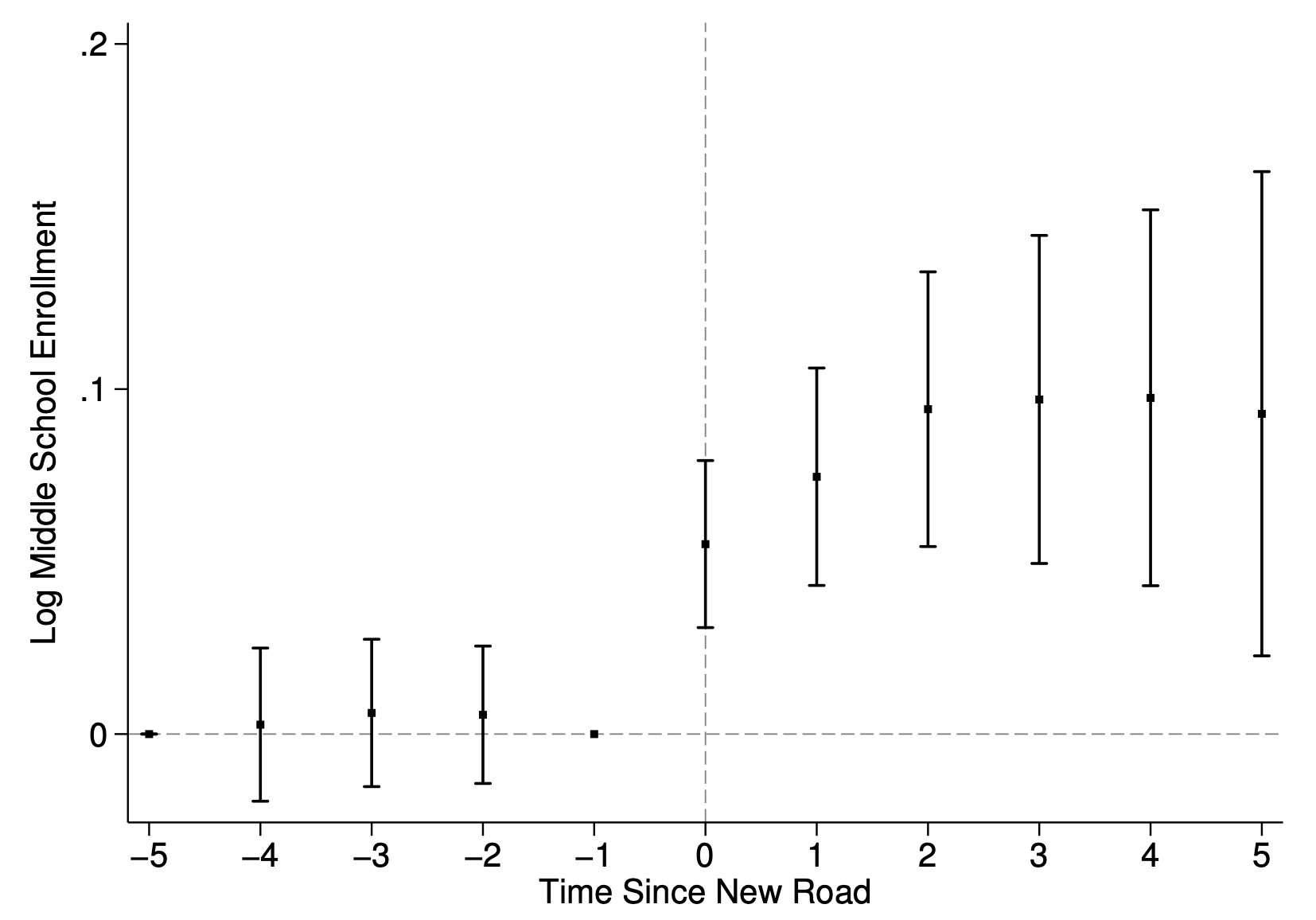

Figure 3 shows the result: a new road caused a 7% increase in middle-school enrolment; there was less impact on primary-school enrolment (which is near universal and had less room to rise), and we did not have data on secondary-school enrolment. We also saw increases in the share of students taking and achieving high scores on standardised tests — in other words, they were not just enrolling in school, they were exerting effort and learning as well.

With the limited data available, it is hard to decisively determine the mechanism through which roads caused these changes. The evidence suggests, however, that it was driven by higher demand for education: once there was better access to outside markets, families saw that there would be a higher benefit in the future if their children were better educated. Specifically, the effects were concentrated in places where the road had the biggest potential to increase the returns to education —villages where the returns to education were particularly low, but the road was connecting them to towns where the returns to education were particularly high. In short, connecting villages to outside markets has likely improved opportunities for the next generation, even if it did not change the economic activities in villages very much.

Figure 3 Middle school enrolment rose after village roads were completed

Note: This figure shows a large and persistent increase in middle school enrolment following a new road construction. The time correspondence and persistent change indicate that the effects are not driven by temporary labour demand shocks from the road construction itself. If that were the case, the effects would disappear after road construction. See Adukia, Asher and Novosad (2020) for details.

Policy implications: Thinking beyond connectivity and market access

Many policymakers have pitched market access infrastructure as a tool that will unlock development in villages, and cause them to become hubs of small-scale manufacturing and services. For instance, the National Rural Roads Development Agency’s planning document argued that roads would reduce poverty by unlocking employment opportunities in villages (2005).

It may not be that simple. There is a growing body of research that suggests that there are many barriers preventing villages from becoming hubs of industrial activity; market access is not a panacea to invigorating their economies. Transformational effects on people’s livelihoods are much more likely to come from helping people get access to places where thriving markets already exist. Indeed, there is plenty of research showing that helping people get out of villages has substantial returns (Bryan, Chowdhury, and Mobarak 2014; Gollin, Lagakos, and Waugh 2014). The effects of policy barriers that make it harder for migrant workers to live in cities (like poor transportation networks and restrictions on housing) are likely underrated, and addressing these may help deliver further improvements to village livelihoods.

Editors’ note: This column was written with the assistance of Aditi Bhowmick.

References

Adukia, A (2017), “Sanitation and education”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 9(2): 23-59.

Adukia, A, S Asher and P Novosad (2020), “Educational investment responses to economic opportunity: Evidence from Indian road construction”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 12(1): 348-376.

Asher, S and P Novosad (2020), “Rural roads and economic development”, American Economic Review 110(3): 797-823.

Asher, S, T Garg and P Novosad (2020), “The ecological impact of transportation infrastructure”, The Economic Journal 130(629): 1173-1199.

Bryan, G, S Chowdhury and A M Mobarak (2014), “Underinvestment in a profitable technology: The case of seasonal migration in Bangladesh”, Econometrica 82(5): 1671-1748.

Burlig, F and L Preonas (2021), Out of the darkness and into the light? Development effects of rural electrification, Working Paper 268R, Berkeley: Energy Institute at Haas.

Gollin, D, D Lagakos and M Waugh (2013), “The agricultural productivity gap”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 129(2): 939-993.

Lipscomb, M, A M Mobarak and T Barham (2013), “Development effects of electrification: Evidence from the topographic placement of hydropower plants in Brazil”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 5(2): 200-231.