Prices don’t always rise after harvest, so rather than store maize and risk selling later at a lower price, farmers may prefer to sell straight away

In much of Sub-Saharan Africa, maize prices tend to fluctuate across seasons, normally reaching annual lows during harvest, rising thereafter, and peaking during the lean season before the next harvest (Kaminski et al. 2014, Kaminski et al. 2016).

Small-farm households tend to sell their grain at harvest when cash is short, and bills are due (Christian and Dillon 2018). Some of these households must return to the market a few months later to repurchase grain in the lean season when their stocks run low. The assumption among development researchers and practitioners has long been that if these farmers could wait and store a portion of their own harvest to sell later when prices typically rise, they would receive a better return on their crop.

But they don’t. This failure to store represents an ongoing problem in development economics policy and research: why are farmers leaving easy money on the table? Why are so many small-scale farmers in the region failing to take advantage of this inter-temporal arbitrage opportunity? Why do they “sell low and buy high”, depressing returns to farming while increasing seasonal malnutrition and food insecurity (Christian and Dillon 2018, Sahn 1989)?

Explanations for this behaviour have centred on liquidity constraints, transaction costs, and limited storage technology (Aggarwal et al. 2018, Burke et al. 2019, Stephens and Barrett 2011) — selling later is possible only if you can access credit to meet consumption needs, pay debts at harvest, and store a crop securely.

Our study

In a recent paper (Cardell and Michelson 2022) we provide a new insight into understanding the failure to store problem. We show that prices don’t always rise after harvest, as sometimes prices fall or stay flat through the lean season; in these years, there isn’t an opportunity for farmers to “sell high”. We quantify this frequency of flat price risk across countries and years to investigate whether the possibility of negative returns on stored cereals (when the lean season price is lower than the harvest price) might contribute to farmer reluctance to store grain.

This phenomenon of flat price risk is ubiquitous across countries and years. We use 20 years of price data from 1183 retail markets in 32 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa collected by the World Food Programme and national agricultural ministries. We identify the harvest and lean season months using data collected by the FAO. We arrive at a “harvest season price” as the minimum price of the months designated as harvest months and a “lean season price” as the maximum price in the 3 months prior to the subsequent harvest, when grain stocks tend to be lowest. This combination of prices defines a lower limit on the probability and the magnitude of negative returns to storage. We calculate returns for each market-year as the percent change in the “lean season price” over the previous “harvest season price.” Our calculations are conservative, abstracting away from the costs of transport, information, and storage.

Previous studies assumed that the average of returns across years was a good indicator of what farmers would earn. The literature has missed something important, and especially important to poor farmers: that averaging across years masks a lot of variability.

Maize prices can decline after harvest

We show that returns to storage are positive on average (across years), but also that flat or declining prices after harvest are common: negative returns occur 16.3% of the time on average in countries with one maize season and between 16% and 25% of the time in countries with two maize seasons. This finding is contrary to prior research that has assumed that higher lean season prices ensure positive returns to storing grain at harvest.

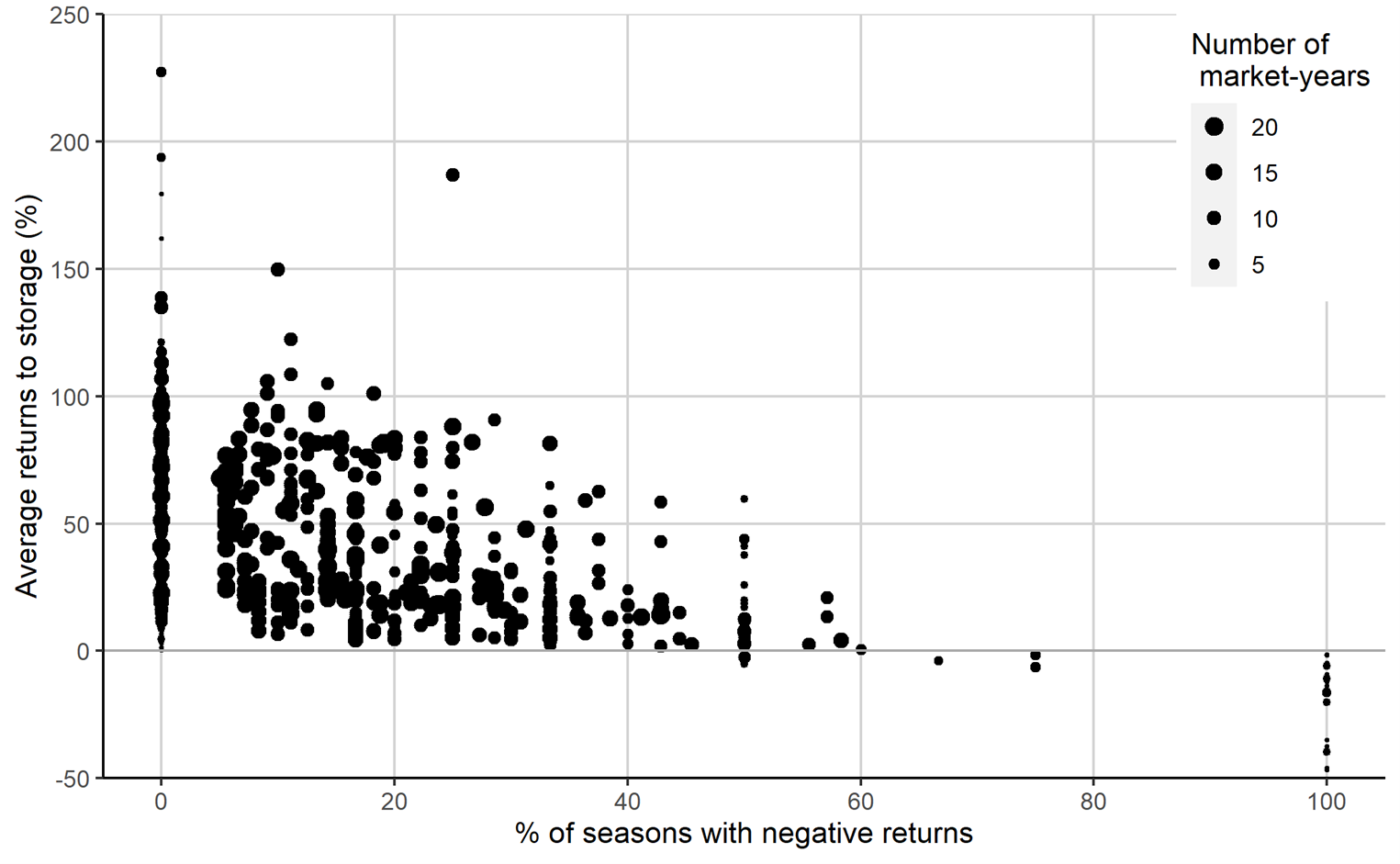

Moreover, the phenomenon of maize prices remaining steady or declining after harvest is not confined to any country or set of years in the data. Each point in Figure 1 represents a specific local retail market. The x-axis presents the percent of seasons in the data in which the market had negative returns. While on average (across years) returns to storage are positive (y-axis) in all but a few markets, nearly all markets exhibit negative returns in some share of market-years.

Figure 1: Retail markets in countries with a single maize season.

Notes: While nearly all markets have positive average returns to storage, the majority also exhibit negative returns in a percent of the observed years.

Returns to storage are unpredictable

A key question is whether a farmer can predict when these returns will be negative or positive. This prediction must be made at harvest; if the harvest price is a sufficient signal of the state of the world (positive or negative returns to storage), then the possibility of negative returns is not a risk for farmers considering storage. If the harvest price is a consistent indicator of future returns, we would expect positive returns to storage to occur in years with low harvest prices, and negative returns in years with higher-than-average harvest prices. Instead, we find that negative returns occur across the distribution of harvest prices, indicating that farmers are unlikely to predict accurately the returns to storage, given information available at harvest time.

Risk-averse farmers should sell at harvest

We work through the implications of a simple model in which the household decides whether to sell grain immediately or store the grain for future sale at the end of harvest. A risk-neutral farmer would be ambivalent between selling at harvest or in the future for the same price, assuming he or she has no access to credit, or other storage or transaction costs, or time preferences over consumption. However, a risk averse farmer would prefer to sell at harvest than at the lean season for the same price, because they don’t know for certain that the price will rise.

Our results suggest that not all farmers would rationally store grain for later sale. We use the WFP price data to determine the share of market-years in each country for which selling grain at harvest is the optimal choice, for a range of farmers with varying tolerance for risk. We show that on average, farmers with a moderate level of risk aversion would opt out of storage in 15.3% of market-years. In market-years in which they opt out, the risk of negative returns is too great relative to what they could earn with certainty at harvest.

Our analysis includes no credit costs, no loss rates or costs for storage, and no outside investment opportunities for farmers. With a conservative interest rate of 5%, the share of market years in which a moderately risk averse farmer opts out of storage increases to 25.2% on average. Storage fees, crop losses in storage, transaction and other carrying costs, and discount rates beyond the interest rate would have similar effects, further increasing incentives to sell at harvest. Maybe farmers are making the right choice given the risks, their preferences and the variability they observe in the returns to storage across years.

Concluding thoughts

Our finding that maize prices don’t always rise after harvest is a new insight and one that raises important questions about how farmers countenance the possibility of negative returns in their storage and investment decisions and what strategies could mitigate these risks. Our results indicate that the probability of negative returns could be an important deterrent of storage and suggest new avenues for research.

References

Aggarwal, S, E Francis, and J Robinson (2018), “Grain Today, Gain Tomorrow: Evidence from a Storage Experiment with Savings Clubs in Kenya”, Journal of Development Economics 134: 1–15.

Burke, M, L F Bergquist, and E Miguel (2019), “Sell Low and Buy High: Arbitrage and Local Price Effects in Kenyan Markets”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 134(2): 785–842.

Cardell, L and H Michelson (2022), "Price risk and small farmer maize storage in Sub-Saharan Africa: New insights into a long-standing puzzle", American Journal of Agricultural Economics.

Christian, P and B Dillon (2018), “Growing and Learning when Consumption Is Seasonal: Long-Term Evidence from Tanzania”, Demography 55(3): 1091–118.

Kaminski, J, L Christiaensen, and C L Gilbert (2014), “The End of Seasonality? New Insights from Sub-Saharan Africa”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 6907.

Kaminski, J, L Christiaensen, and C L Gilbert (2016), “Seasonality in Local Food Markets and Consumption: Evidence from Tanzania”, Oxford Economic Papers 68(3): 736–757.

Stephens, E C., and C B Barrett (2011), “Incomplete Credit Markets and Commodity Marketing Behaviour”, Journal of Agricultural Economics 62(1): 1–24.

DISCLAIMER:

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the author(s) and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or U.S. Government determination or policy. This article was supported [in part] by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.