Engaged communities of parents are a potential nonscarce resource to promote the success of education programmes at scale

A key challenge in using scientific insights to inform policy decisions arises during the implementation process, where small changes between interventions translate into substantial differences in outcomes. Scholars are increasingly concerned about this issue, particularly given the failure of certain interventions to replicate the effects found in small-scale randomised trials when implemented at a larger scale by governments or firms (Banerjee et al. 2017, Muralidharan and Niehaus 2017, Al-Ubaydli et al. 2020, List 2022).

In our recent study (Agostinelli, Avitabile, and Bobba 2022), we contribute to this debate about the challenges of scaling up education interventions. We use a case study involving a mentoring programme that was evaluated at scale in Chiapas, the poorest state in Mexico.1 The programme assigns recent university graduates to remote and disadvantaged communities. Among other tasks, mentors encourage parental involvement in children’s education through home visits. We evaluate the relative effectiveness of two programme modalities that differ in terms of both the content and intensity of the training provided to the frontline mentors. The Original modality, which was initially implemented by the government, features a training module focused on curricular knowledge and pedagogical notions. The Plus modality embeds a significant change in the training module. First, it entails two weeks rather than one week of initial training. The extra week is focused on hands-on strategies to improve students’ reading and math competencies. Second, mentors attend periodic peer-to-peer sessions throughout the school year in which they share experiences and design common strategies to better manage their interactions with families.

Experimental evidence

The evidence on the relative effectiveness of the two programme modalities is drawn from two independent field experiments. The government directly carried out the first experiment during the ongoing national rollout of the Original modality of the mentoring intervention. The results show that the programme had no discernible effect on children’s achievement outcomes, as measured by standardised test scores. In the second experiment, we randomly assign children to a mentor from either the Original or the Plus modality, as well as a control group who receive no mentoring program. After two years of exposure to the mentoring programme, the Original programme modality displays relatively small and noisy effects on cognitive and socio-emotional scores, as well as on educational achievements, when compared to the control group with no mentors. The Plus modality delivers sizable and significant gains in children’s reading scores (+0.32 standard deviations), maths scores (+0.24 standard deviations), and socio-emotional scores (+0.20 standard deviations), while also significantly increasing the probability of enrolling in the first grade of secondary school (+12.7 percentage points, on a baseline of 62% enrollment in the control group).

The large difference in effect sizes between the two training modalities is corroborated by direct evidence on parental behaviour. While there is inconclusive evidence on parents’ investment under the Original modality, the Plus modality significantly increases parental engagement towards both the child’s education activities and the school community – as seen by increased volunteering activities and in-kind donations to schools. Furthermore, we find evidence that mentors with enhanced training engage in higher-quality interactions with parents during the periodic encounters. In particular, mentors with enhanced training are more likely to inform parents about their children’s learning difficulties, to provide concrete advice to parents on how to tackle these difficulties, and also to promote parenting styles that are centred around communicating with the child and learning activities.

Threats and channels of scalability

After the release of this evidence, the government autonomously decided to replace the Original modality of the programme with the Plus modality for all its primary schools throughout the country, including those that were part of the experimental evaluation. One of the key situational differences between the experimental setting and the wider policy implementation is that outside the experiment, schools are at a higher risk of closure, an event that has disruptive consequences for children’s learning and their educational trajectories. Hence, a threat to the success of the programme in the new policy situation may come from the possible school closures as a result of the mentoring intervention under the government implementation. Two years after the rollout, none of the schools that received a mentor during the government implementation closed, while approximately 10% of the other schools without mentors did.

We sketch a simple model of parental investment with local spillovers to formalise the idea that parents have an active role in promoting educational opportunities. In the model, the extent to which an educational programme preserves or loses impact at scale depends upon its ability to promote parental coordination and engagement in the local community. We empirically corroborate these predictions by leveraging the changes in community-level parental engagement induced by our second experiment. Using this variation, we document that parents prevent schools from closing, and in turn promote the effectiveness of the mentoring intervention during the government implementation. While previous literature posited the role of parents as key actors for boosting treatment effects of home visiting programmes (Heckman and Zhou 2021, Zhou et al. 2021), our work highlights the socially determined nature of scaling educational programmes through parental cooperation in the local educational activities.

Policy impacts at scale

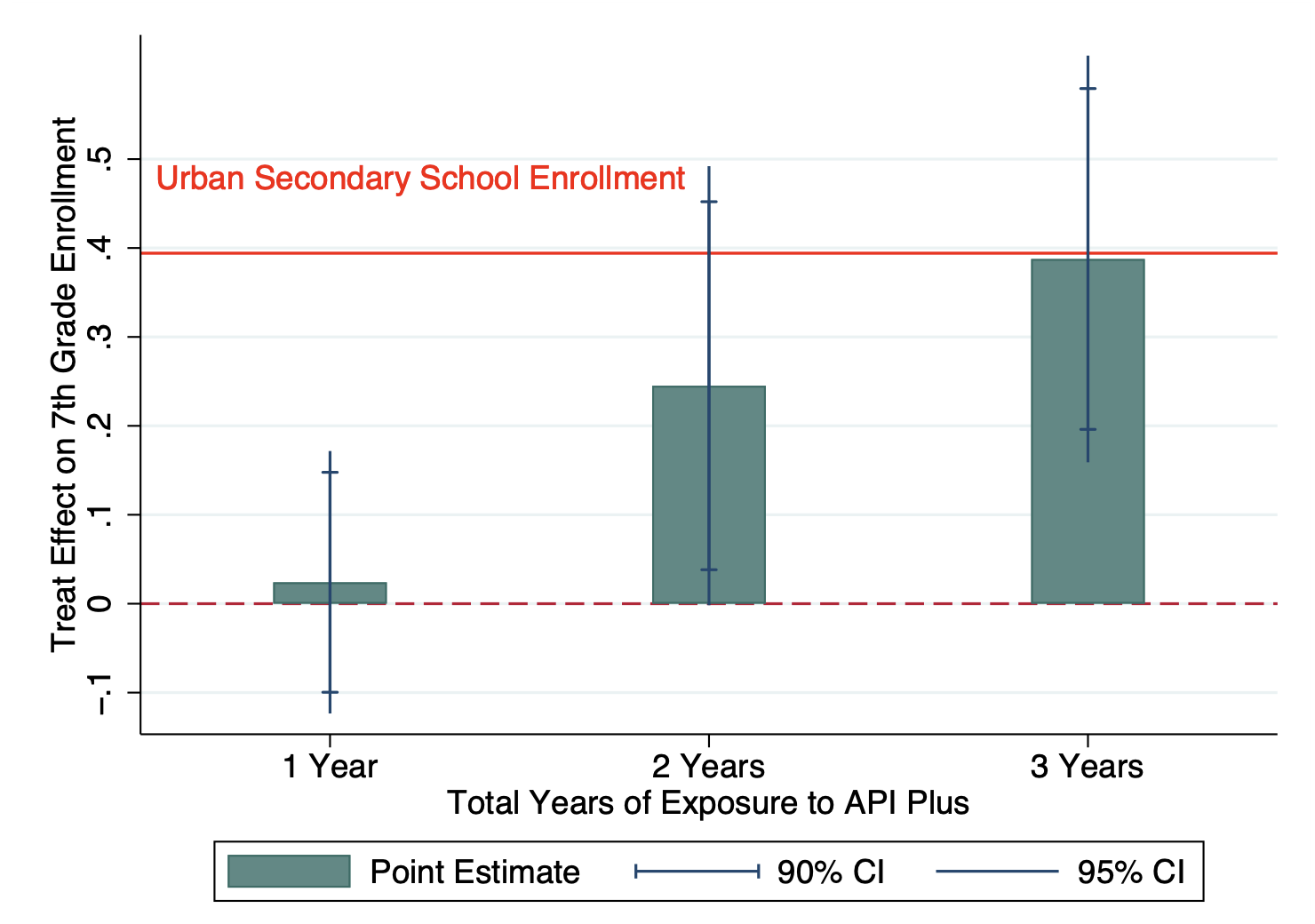

Finally, we show that the programme as implemented by the government was broadly successful. The assignment of the mentoring programme under the Plus modality at scale was done through a rotating scheme with a priority-based mechanism. We exploit the quasi-experimental variation in the programme rollout once we condition on the set of eligibility criteria officially used by the government. Within the schools that were previously part of the evaluation sample, the marginal effect of the Plus modality after one year of government implementation on the probability of enrolling in seventh grade is +5.4 percentage points. The cumulative effect of continuous exposure to the program for three years (two years under the experiment and one year under the government) implies that the enrollment rates in these disadvantaged and rural areas achieve the secondary school enrollment rates seen in urban Mexico (Figure 1).

Figure 1 The exposure effect of the program in the evaluation schools

Notes: This figure shows OLS estimates of the years of exposure to the mentoring program on the probability of enrolling in seventh grade during the transition from the second experiment to the government implementation of the Plus modality. Vertical lines overlaid on each bar display the 95 percent and 90 percent confidence intervals, respectively. Confidence intervals are based on asymptotic inference.

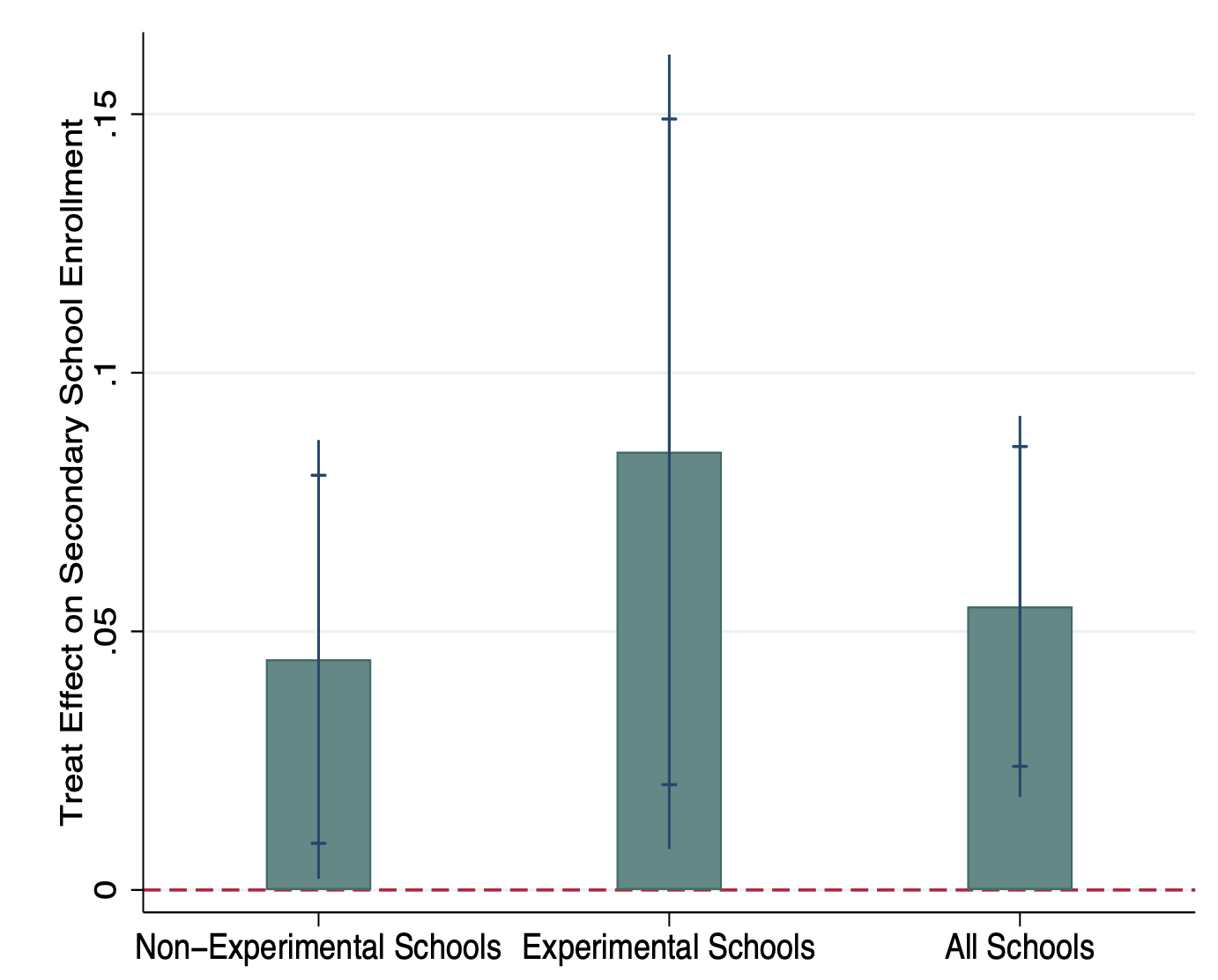

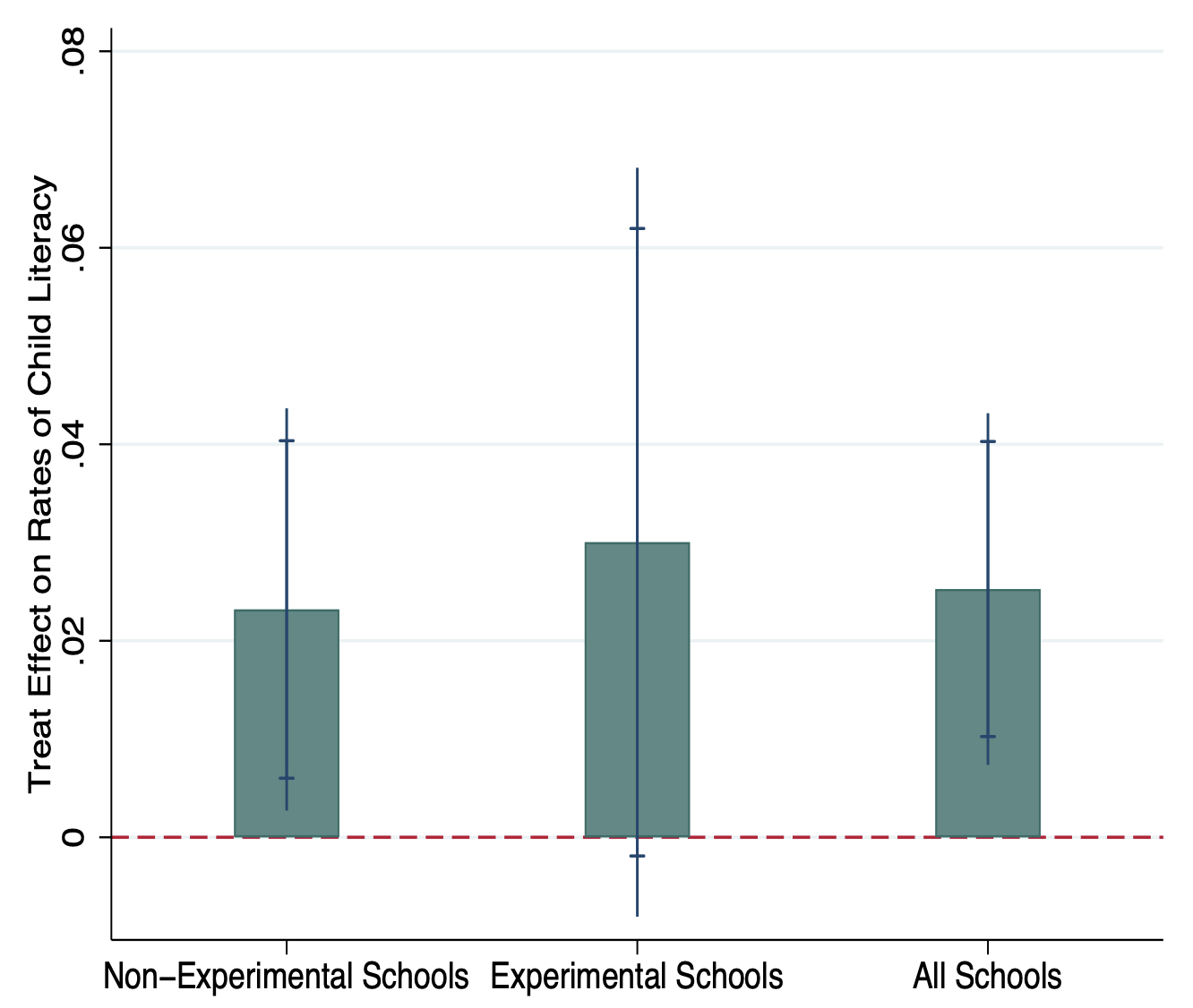

For the much larger sample of schools that did not participate in the experimental evaluation, the results show a positive effect on secondary school enrollment, with an average programme impact of 5.5 percentage points under the Plus modality at scale. Atop this, we document positive effects of the program on child literacy, which imply a reduction of illiteracy rates by 20% with respect to the sample mean (Figure 2). Taken together, these findings corroborate the effectiveness of the intervention in improving schooling opportunities.

Figure 2 Policy impact across all schools

Panel A) Secondary school enrollment

Panel B) Child literacy

Notes: The bars in the figure represent the OLS estimates of the assignment to the API program during the government implementation of the Plus modality on school-level secondary school enrollment rates (Panel A) and child literacy rates (Panel B). Vertical lines overlaid on each bar displays the 95 percent and 90 percent confidence intervals, respectively. Confidence intervals are based on asymptotic inference.

Implications for scaling

We hope that our results can promote a policy-relevant discussion and future research on how to design mentoring interventions in disadvantaged contexts, which actively target parental engagement at the community level. Parents in local communities are available with no supply-side restrictions, but their local engagement must not be taken for granted. The details in the mentoring modalities and the resulting quality of the home visits are pivotal in generating parental responses, which in turn may sustain or hamper the scalability of education interventions.

References

Agostinelli F, C Avitabile and M Bobba (2022), “Enhancing Human Capital in Children. A Case Study on Scaling,” HCEO Working Paper 2021-012.

Al-Ubaydli, O, J A List and D Suskind (2020), “2017 Klein Lecture: The Science of Using Science: Toward an Understanding of the Threats to Scalability,” International Economic Review 61(4): 1387–1409.

Banerjee, A, R Banerji, J Berry, E Duflo, H Kan-nan, S Mukerji, M Shotland and M Walton (2017), “From Proof of Concept to Scalable Policies: Challenges and Solutions, with an Application,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 31(4): 73–102.

Heckman, J J and J Zhou (2021), “Interactions as Investments: The Microdynamics and Measurement of Early Childhood Learning,” Working Paper, Center for the Economics of Human Development, University of Chicago.

List, J A (2022), The Voltage Effect: How to Make Good Ideas Great and Great Ideas Scale, Penguin Books.

Muralidharan, K and P Niehaus (2017), “Experimentation at Scale”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 31(4): 103–124.

Zhou, J, A Baulos, J J Heckman and B Liu, “The Economics of Child Development with an Application to Home Visiting at Scale” in J A List, D Suskind, and L H Supplee (eds), The Scale-up Effect in Early Childhood and Public Policy, Routledge.

Endnotes

1 The overall scale of the operation of the mentoring intervention – including the total number of mentors that participated in the programme – remained constant in the periods before, during, and after the experiments. The relatively large units of randomisation (school community) are robust to local general equilibrium/spillover effects, which are often relevant in field experiments that are implemented during the national rollout of a program. The second experiment has been implemented by the research team in close collaboration with the government agency that was later in charge of the policy implementation. Hence, the design of the two program modalities bears in mind the supply-side considerations of scaling, as well as various financial and local institutional constraints.