A merit-based teacher hiring reform succeeded in recruiting teachers with better qualifications, but the replacement of more experienced teachers led to a decline in student outcomes.

Teacher quality is widely recognised as a key determinant of student learning (Chetty et al. 2014, Hanushek and Rivkin 2006, Rivkin et al. 2005). The methods by which teachers are recruited, selected, and retained are of significant interest to policymakers seeking to improve student outcomes. In an effort to foster learning, several countries have implemented nationwide reforms to modify hiring systems, often relying on a range of criteria, including standardised admission tests (Cruz-Aguayo et al. 2020, Robalino and Korner 2007). The success of these systems depends on their ability to accurately identify high-quality teachers through these exams. However, predicting teacher quality based on observable characteristics, such as test scores, remains a challenge (Rockoff et al. 2011, Harris et al. 2014).

In our recent paper (Busso et al. 2024), we explore how well-intentioned reforms designed to objectively identify high-quality teachers through written exam screenings may inadvertently backfire if other important predictors of teacher effectiveness, such as teaching experience, are overlooked. Our findings highlight the importance of carefully balancing teacher characteristics when designing hiring mechanisms for public educators. These mechanisms have far-reaching implications for the economic prospects of future generations, making them a critical issue for educational policy.

Colombia implemented a merit-based teacher hiring reform in 2005

To address this topic, we study a teacher hiring reform implemented in Colombia in 2005. The reform introduced an admission exam for all public teachers. This reform represented a bold attempt to overhaul its public school system by introducing a centralised, merit-based hiring system for teachers. The reform aimed to professionalise teaching and eliminate the politicised practices that had characterised hiring decisions in the past. It sought to identify and recruit more academically skilled educators, replacing the previous decentralised hiring system that often lacked transparency and consistency.

Under the new system, teacher candidates were evaluated based on their performance on a standardised national exam designed to measure cognitive skills, subject-specific knowledge, and teaching aptitude. Successful candidates were ranked based on their scores, and vacancies were filled by allowing top-ranked applicants to select from available positions. While this approach prioritised fairness and sought to attract more qualified candidates, it heavily weighted exam scores over other factors, such as teaching experience. Additionally, the reform increased starting salaries for teachers to make public school teaching positions more attractive.

The Colombian policy reform attracted ‘more qualified’ teachers but sacrificed experience

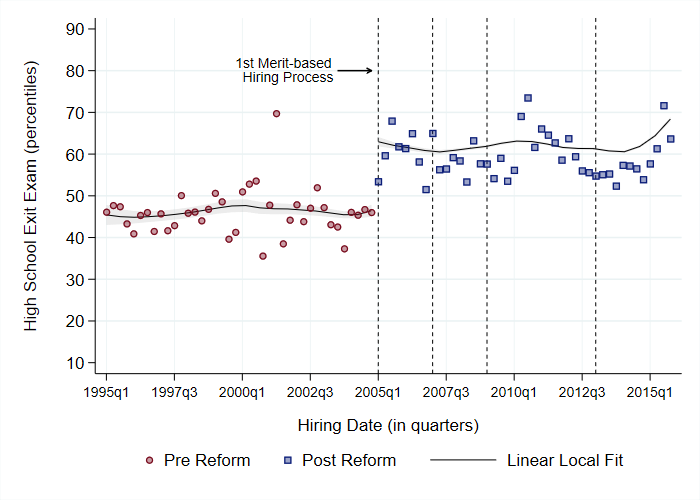

The policy led to a drastic change in the pool of candidates recruited to fill the teaching positions. Newly hired teachers seemed to be more qualified as they scored, on average, 17 percentile points higher on pre-college test scores, a measure of cognitive abilities. At first glance, this approach seemed like a positive step for Colombia’s public education.

Figure 1: The reform hired teachers with better cognitive abilities

However, the reform had significant unintended consequences. Within a few years of implementation, the merit-based hiring system led to the replacement of many experienced contract teachers with novice teachers who had higher test scores but little to no classroom experience. By 2007, nearly 40,000 experienced contract teachers—roughly 13% of all public school teachers—had been replaced by newly hired educators. This rapid turnover of teaching staff caused a sharp decline in the overall level of teaching experience across public schools. The proportion of teachers with fewer than five years of experience tripled, rising from 10% in 2004 to 30% by 2008. This loss of experienced teachers had significant implications for students’ academic outcomes.

The hiring reform had negative effects on students’ learning in Colombia

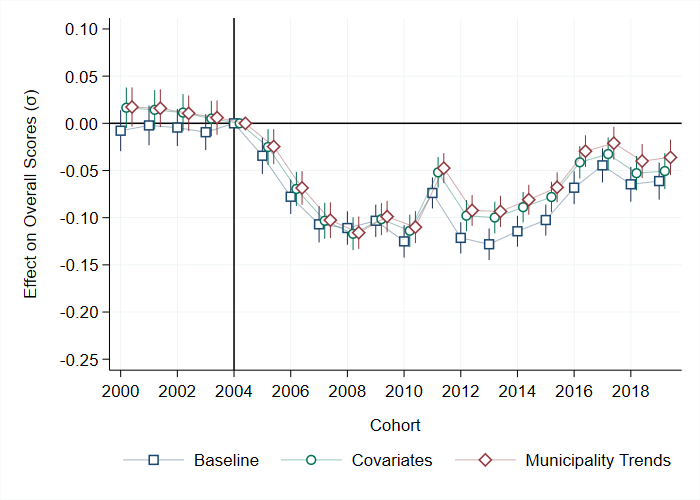

The reform led public school students to experience an average decline of 8% of a standard deviation in their standardised test scores, with particularly large drops in mathematics and English. These declines were comparable to the negative effects associated with being taught by a first-year teacher or a one-standard-deviation decrease in teacher quality, as documented in global education research.

Figure 2: The reform decreased student test scores

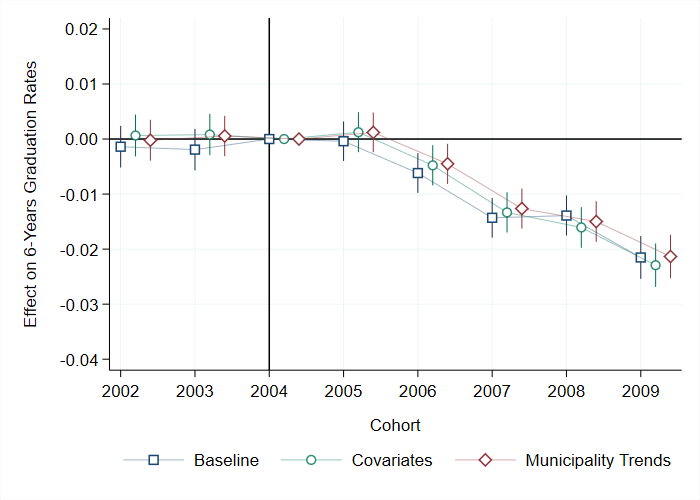

The consequences were not limited to test scores. The reform also reduced college enrolment and graduation rates among public school students. College enrolment dropped by 3.3 percentage points, representing a 21% decrease in the likelihood that public school students would pursue higher education. Among those who did enrol, the likelihood of graduating from college fell by nearly 10%. These declines were likely driven by the lower test scores, as many Colombian universities use standardised test performance as a key criterion for admissions.

Figure 3: The reform decreased college graduation

Negative student outcomes were related to increased exposure to novice teachers

While the reform succeeded in attracting teachers with higher academic credentials, it failed to account for the importance of teaching experience. Research consistently shows that teachers are less effective during their first few years in the classroom, as they lack the practical skills and classroom management strategies that come with experience. The reform’s focus on cognitive skills and test scores overshadowed this critical dimension of teacher quality. Schools with a higher proportion of novice teachers— those in urban areas or with higher pre-reform test scores—experienced more severe declines in student performance, indicating that the influx of inexperienced educators was a primary driver of the negative effects.

The reform also created instability within the public school system. The large-scale replacement of experienced teachers with novice teachers disrupted continuity in the classroom. Moreover, the centralised nature of the hiring system made it difficult to fill all vacancies, particularly in remote or low-income areas. As a result, these schools often relied on temporary contract teachers, exacerbating turnover and further reducing the overall stock of teaching experience. The reform’s implementation was also uneven, with delays in public calls for new hires creating gaps in staffing and increasing reliance on less experienced contract teachers in the interim.

Teacher experience, retention, and implementation challenges should not be overlooked

The experience of Colombia’s reform offers critical lessons for policymakers. First, it highlights the risks of over-relying on standardised test scores as a measure of teacher quality. While cognitive skills are an important component of effective teaching, they are not sufficient on their own. Teaching is a complex profession that requires a combination of subject knowledge, pedagogical skills, and experience. Policymakers should adopt a more holistic approach to teacher recruitment that balances cognitive measures with other indicators of teaching potential, such as classroom performance and prior experience.

Second, the reform underscores the importance of teacher retention and stability. High turnover rates disrupt schools and negatively impact student learning. Policies that replace experienced teachers with novice educators may undermine efforts to improve education quality, even if the new hires have stronger academic credentials. Ensuring job stability and creating clear career pathways for teachers can help retain experienced educators and reduce turnover.

Third, the Colombian case illustrates the importance of considering implementation challenges in education reforms. The centralised hiring system introduced significant logistical and administrative complexities, including delays in filling vacancies and uneven distribution of teachers across schools. Policymakers should prioritise efficient implementation and ensure that reforms are designed to minimise disruptions to the education system.

Despite its challenges, the reform was well-intentioned and aligned with global efforts to professionalise the teaching career, select teachers through objective standards, and improve education quality. Similar merit-based hiring systems have been adopted in other countries, including Chile, Mexico, and Ecuador, with mixed results. The Colombian experience underscores the need for careful design and evaluation of such policies to avoid unintended consequences.

References

Busso, M, S Montaño, J Muñoz-Morales, and N Pope (2024), “The unintended consequences of merit-based teacher selection: Evidence from a large-scale reform in Colombia,” Journal of Public Economics, November 2024, 105238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2024.105238.

Chetty, R, J Friedman, and J Rockoff (2014), “Measuring the impacts of teachers II: Teacher value-added and student outcomes in adulthood,” American Economic Review, 104(9): 2633–2679.

Cruz-Aguayo, Y, D Hincapie, and C Rodríguez (2020), “Testing our teachers: Keys to a successful teacher evaluation system,” Inter-American Development Bank. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.18235/0002149.

Hanushek, E, and S Rivkin (2006), “Teacher quality,” in Handbook of Economics of Education, pp. 1051–1078, Elsevier.

Harris, D, W Ingle, and S Rutledge (2014), “How teacher evaluation methods matter for accountability: A comparative analysis of teacher effectiveness ratings by principals and teacher value-added measures,” American Educational Research Journal, 57(1): 73–112.

Rivkin, S, E Hanushek, and J Kain (2005), “Teachers, schools, and academic achievement,” Econometrica, 73(2): 417–458.

Robalino, M, and A Korner (2007), Evaluación del desempeño y carrera profesional docente: Un estudio comparado entre 50 países de América y Europa, UNESCO, Oficina Regional de Educación para América Latina y el Caribe.

Rockoff, J, B Jacobs, T Kane, and D Staiger (2011), “Can you recognize an effective teacher when you recruit one,” Education Finance and Policy, 6(1): 43–74.