Mexico’s preschool mandate in 2002 shows significant, lasting benefits for cognitive skills and non-cognitive skills after six years, and educational outcomes nearly two decades later.

In the early 2000s, Mexico made a groundbreaking decision to make preschool education mandatory for all children. This bold move aimed to give every child a strong start in life by ensuring they attend three years of preschool before entering primary school. The reform was rolled out gradually, starting in 2004. The idea behind this initiative was simple: investing in early childhood education could have long-lasting benefits. By providing structured learning environments from a young age, the government hoped to improve children's cognitive skills, such as maths and language abilities, as well as noncognitive skills, such as attention and social behaviour.

Are the impacts of preschool long-lasting?

Spending on early childhood educational programmes and enrolment in preschool has grown across the developing world during the past two decades. However, whether such programmes have lasting impacts remains a matter of debate. A key concern has been ‘fade-out’, with many studies reporting initial improvements in learning outcomes but finding that the effects do not last, even through primary school (Duncan and Magnuson 2013). A few studies for high-income countries do however find longer-term positive effects of preschool on completed education, earnings and reduced participation in crime (see, for example, Currie and Thomas 1995, Heckman et al. 2010, Bailey et al. 2021).

A central policy question is whether the fade-out of initial test scores might imply that preschool programmes are ineffective (perhaps due to low quality) or whether other benefits might emerge over the longer-term. Unfortunately, most evidence focuses on universal preschool programmes in high-income country settings or on small field experiments (notable exceptions are Berlinski et al. 2008 and, Berlinski and Gertler 2009).Very little is known about the effects of larger universal preschool programmes in low- and middle-income country (LMIC) settings, where scaling up successful programmes may be challenging. Yet to improve child well-being around the world, evidence on effective universal and scaled-up programmes is urgently needed.

The universal preschool mandate in Mexico

In 2002, Mexico passed a law mandating three years of preschool education as part of the compulsory-education system. This legislation stipulated that parents have legal responsibilities to enrol their children in preschool. The reform was phased-in over several years, starting with mandatory attendance for five-year-olds in 2004 and extending to three- and four-year-olds by 2008. A UNICEF report (Yoshikawa et al. 2007) documents a significant initial surge in enrolment rates following the mandate.

Measuring the effects of the preschool mandate

In new research (Behrman et al. 2024), we study whether the preschool mandate led to sustained improvements in academic performance, noncognitive skills, student engagement, and overall educational attainment. We leverage the eligibility birthdate for enrolment into preschool turning age five before September 1st, 1998. We compare outcomes for children born right after this date (and thus subject to the preschool reform) with those born right before (and thus not subject to the reform). Using birth dates as an instrument for schooling outcomes was initially pioneered in Angrist and Krueger (1991).

However, because for many Mexican states, September 1st is also used as a cutoff birthdate for entering primary school, we compare discontinuities in outcome measures around the September 1, 1998 reform-eligibility threshold (the birth-date cutoff for the initial phase of the reform), to discontinuities in outcomes around September 1 of the preceding pre-reform year. We use a unique national longitudinal administrative test-score database, measuring student achievement in math and Spanish over a seven-year period, integrated with enrolment-roster information and data on students' school engagement/participation and noncognitive skills.

Key findings on the impact of preschool in Mexico

1. Improved cognitive skills persist beyond early years.

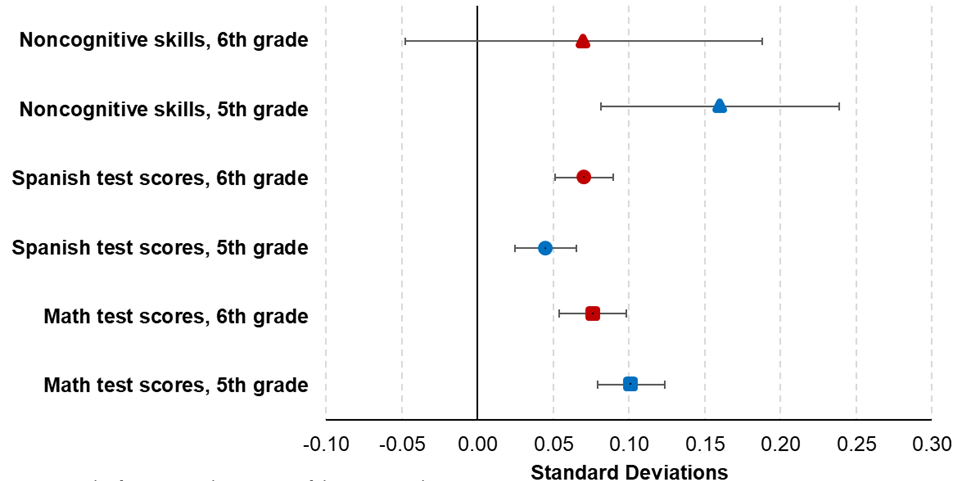

We find that the preschool mandate had positive impacts on students' academic performance 5-6 years later in primary school. Specifically, children who attended preschool under the mandate scored higher in fifth and sixth-grade maths and Spanish tests, with maths scores increasing by 0.08-0.10 standard deviations and Spanish scores by 0.04-0.07 standard deviations (Figure 1). These gains are notable because some studies based on developed countries indicate that the benefits of early childhood education often fade out by the second grade. However, in Mexico, the positive effects persisted into later primary school years.

Figure 1: Medium-term impacts of the preschool mandate on skill formation

Note: The figure considers 95% confidence intervals.

2. Enhanced school engagement and reduced failure rates.

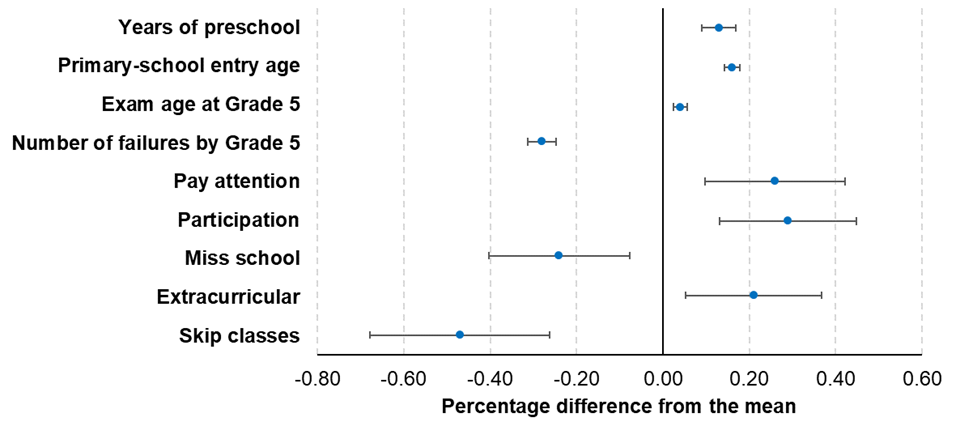

The mandate led to higher levels of school engagement among students. Children who attended preschool were more likely to pay attention in class, participate in school activities, and complete their homework. These behaviours are likely essential for academic success and overall development. Our research found that the mandate reduced the likelihood of children skipping classes and increased their participation in extracurricular activities, which are important for social and emotional development. Children subject to the mandate also had lower failure rates in primary school. As a result, they progressed more smoothly through grades (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Medium-term impacts of the preschool mandate on 5th grade school engagement and performance

Note: The figure considers 95% confidence intervals.

3. Improved non-cognitive skills.

In addition to academic performance, the preschool mandate also improved noncognitive skills, known to be critical predictors of long-term success, according to existing literature (Heckman et al. 2013). Noncognitive skills include traits like conscientiousness, attention, and social behaviours. The study used a summary index to measure these skills and found that the mandate increased noncognitive skills by 0.07-0.16 standard deviations.

4. Beyond primary-school ages: Preschool’s long-term educational outcomes.

We also examined the long-term impacts of the preschool mandate on educational attainment. Using data from the National Survey of Employment and Occupation (ENOE), we found that the mandate increased the likelihood of completing high school and enrolling in college. Specifically, the probability of finishing high school increased by 8.7 percentage points, and the likelihood of attending some college increased by 11.1 percentage points. These findings suggest that the benefits of preschool education extend well through adolescence and into young adulthood.

What do we learn from the Mexican preschool mandate?

The policy implications from our research (Behrman et al. 2024) are significant and multifaceted, underscoring the importance of investing in early childhood preschool education. Mexico’s preschool mandate provides valuable lessons for other LMICs looking to improve their educational systems. Unlike in some HIC contexts, where cognitive gains from early education diminish over time, this study suggests that universal preschool policies can have sustained effects on cognitive and non-cognitive outcomes when implemented at scale.

The broader implications extend beyond education alone. By fostering early cognitive development and engagement in school, preschool programmes can help reduce inequality, improve long-term educational outcomes, and ultimately contribute to human-capital formation in developing countries. Policymakers in LMICs should consider scaling up investments in preschools, especially in contexts where access to preschool remains limited for disadvantaged populations.

Nearly two decades after its implementation, Mexico’s universal preschool mandate continues to yield significant educational benefits. These findings challenge the notion of cognitive fade-out and emphasise the importance of preschool investments. By improving both cognitive and non-cognitive skills, the preschool mandate set a strong foundation for children’s long-term success, making it a model for other countries to follow.

References

Angrist, J D, and A B Krueger (1991), “Does compulsory school attendance affect schooling and earnings?” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(4): 979–1014. https://doi.org/10.2307/2937954.

Bailey, M J, S Sun, and B Timpe (2021), “Prep school for poor kids: The long-run impacts of Head Start on human capital and economic self-sufficiency,” The American Economic Review, 111(12): 3963–4001.

Behrman, J, R Gomez-Carrera, S Parker, P Todd, and W Zhang (2024), “Starting strong: Medium- and longer-run benefits of Mexico's universal preschool mandate,” Mimeo. Available here.

Berlinski, S, S Galiani, and M Manacorda (2008), “Giving children a better start: Preschool attendance and school-age profiles,” Journal of Public Economics, 92(5-6): 1416–1440.

Berlinski, S, and P Gertler (2009), “The effect of pre-primary education on primary school performance,” Journal of Public Economics, 93(1-2): 219–234.

Currie, J, and D Thomas (1995), “Does Head Start make a difference?” The American Economic Review, 85(3): 341–364.

Duncan, G, and K Magnuson (2013), “Investing in preschool programs,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27(2): 109–32.

Heckman, J, R Pinto, and P Savelyev (2013), “Understanding the mechanisms through which an influential early childhood program boosted adult outcomes,” The American Economic Review, 103(6): 2052–2086.

Yoshikawa, H, K McCartney, R Myers, K Bub, J Lugo-Gil, M A Ramos, and F Knaul (2007), “Early childhood education in Mexico: Expansion, quality improvement and curricular reform,” Innocenti Working Paper, UNICEF.