As countries in Sub-Saharan Africa debate the costs and benefits of subsidising secondary education, a 15-year RCT in Ghana finds large multi-generation impacts.

Secondary education has become a greater priority for policymakers, as free primary education policies adopted over the past few decades have led to almost universal primary school enrolment in low-income countries today (World Bank 2023). Although UN Sustainable Development Goals call for “free, equitable, and quality primary and secondary education” by 2030, in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), upper secondary education completion is less than 33%.

In an effort to expand education beyond primary school, a number of SSA countries have introduced free secondary education. Currently, nearly half of SSA countries offer free lower secondary education (grades 6-9), while one-third offer free upper secondary (grades 10-12). This marks significant progress from the early 2000s when the first countries in the region began eliminating fees (Grujiters 2023). Fee elimination has been found to increase attendance and school completion considerably. For example, in Kenya, removing fees led to a 6-16 percentage point increase in total enrolment (Brudevold-Newman 2021). Likewise, in Gambia, fee elimination increased the number of girls taking the high school exit exam by 55% (Blimpo et al. 2016). Non-fee subsidies, such as those on uniforms, have also shown to have similar effects (Duflo et al. 2015).

Using an RCT to study the effectiveness of secondary school subsidies in Ghana

Despite its impact on enrolment, there continues to be debate over whether secondary education should be subsidised, given limited public resources and unclear broader outcomes. For instance, despite increasing national enrolment by almost 50% in one year, the free senior high school policy adopted by Ghana in 2017 has since been the subject of criticism. Opponents of the programme have cited concerns over high costs and the strain on schools as a result of increased enrolment, in addition to uncertainty on the quality and benefits of expansion (Grujiters 2023).

In 2008, Duflo et al. (2021) launched a randomised controlled trial (RCT) to better understand the benefits of subsidies for secondary education. The study took place in Ghana prior to the introduction of the free senior high school policy. Specifically, full scholarships were awarded to around 700 rural students to attend high school. Outcomes of recipients, alongside those of a control group of roughly 1,400 students, were tracked for the next 15 years. Both recipients and non-recipients were randomly selected from a group of students who had passed the senior high school (SHS) entrance exams and could not afford to attend their local secondary school.

This sample was distributed across 177 schools and 54 different districts (almost 25% of all SHSs in the country), evenly split between boys and girls. The study measured outcomes through a mix of in-person and phone surveys over 15 years, and had only ~5% total attrition until 2020 and <10% total in the three years following. In 2017, we started tracking outcomes for the children of both recipients and non-recipients (Duflo et al. 2024). This involved in-home visits to implement state-of-the-art cognitive tests at various stages of early childhood development.

The impact of high school scholarships is especially pronounced for girls

The results of this intervention are dramatic, providing convincing evidence on the benefits of secondary education expansion for recipients and their future generations, especially female recipients. Evidence suggests that scholarship benefits are also highly cost-effective, with a cost-benefit ratio of almost 1:30 (and potentially as high as 1:110).

In line with similar research on fee elimination, scholarship recipients were almost 30 percentage points more likely to graduate. This effect is similar for boys and girls. However, downstream impacts are heterogeneous by gender. Female recipients had nearly double the rate of tertiary school attendance vs non-recipients; by their late 20s, female recipients had 25-30% higher income than non-recipients. Neither of these downstream impacts are observed among males.

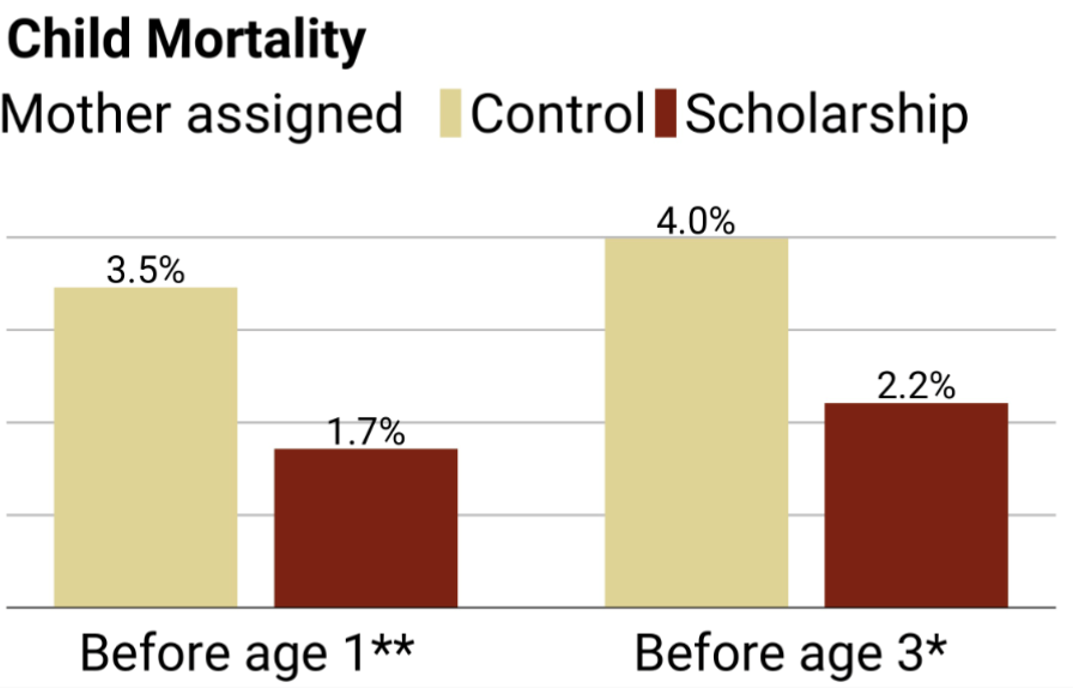

The long-run effects on family formation and outcomes also differ markedly by gender, however. Female recipients had nearly 15% fewer unplanned pregnancies, 15% fewer children, along with a significantly delayed age at first childbirth and marriage, unlike their male counterparts. These impacts on family structure are consistent with those of a recent study providing girls scholarships in Niger (Giacobino et al. 2024). However, the effects on female recipients did not stop there. Over time, their offspring’s outcomes improved dramatically as well: children had 45% lower under-3 mortality rates (Figure 1), as well as significantly improved cognitive scores once of school age.

Figure 1: Child mortality rates of recipients vs. non-recipients

High school scholarships can be a cost-effective human capital policy with benefits extending multiple generations

To measure child development, the Harvard Laboratory for Development Studies spent time in Ghana developing a broad set of tests. These involved in-person interactive games testing language, memory, executive function, numerical and spatial reasoning, and social-cognitive skills. Tests were administered based on child’s age every 12 to 24 months. By age 5 and 7, improvements in performance on these tests were comparable in magnitude (if not greater) to recipient mothers’ own learning gains from attending secondary school. Tests also point to the cause of these effects by measuring children’s linguistic environments, which showed that recipient mothers and children spoke more frequently than children of male recipients and those in the control group. We expect results did not hold for male recipient families as (1) men were rarely primary caretakers, and (2) the children of male scholarship recipients had mothers no more likely to have received secondary education than those in the control group.

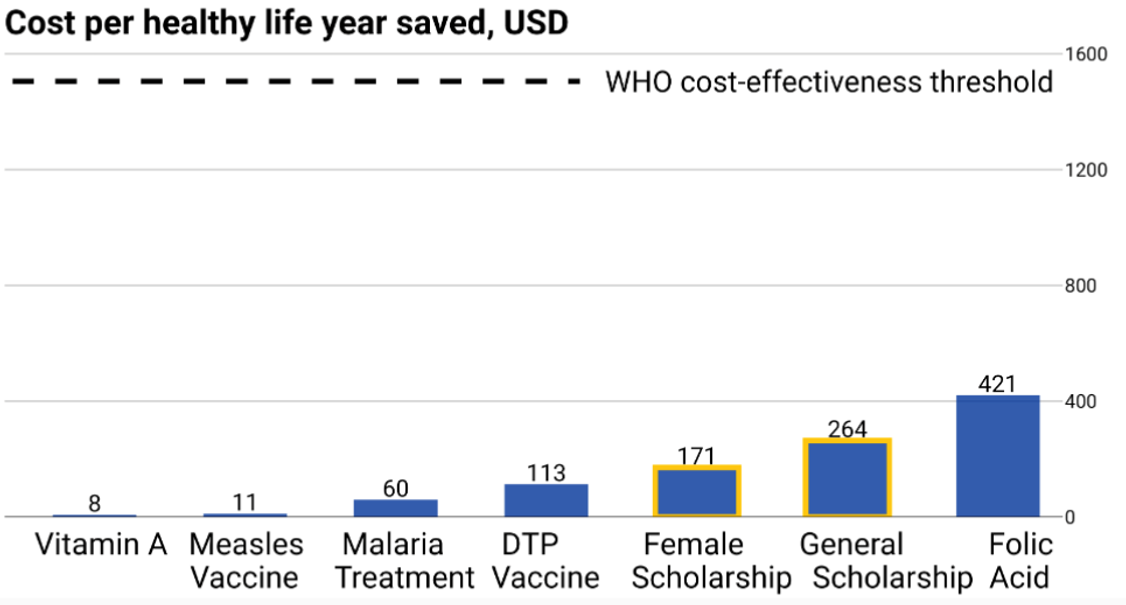

Combining these multigenerational benefits demonstrates very high cost-effectiveness. The intervention yielded benefits ranging from 6 to 56 times its costs overall, and from 10 to 110 times when targeted at girls specifically. Isolating impacts on infant mortality, the intervention costs $170-260 per life-year saved (depending on whether targeting only to girls), making it a competitive public health policy by WHO standards (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Cost per healthy life year saved of health interventions

Notes on scholarship interventions: Source is data collected by authors. Scholarships assumed to be means-tested. The total cost of 4 years of senior high school is estimated to be $505 for women, including forgone wages. Estimates assume 89 healthy life years for newborns. Notes on other interventions: Source is Stenberg et al. (2021). All selected interventions recommended by the WHO. Estimates based on treating a population of 1 million people in East Sub-Saharan Africa and an 80% coverage rate. Folic acid includes daily supplements during pregnancy. Vitamin A includes supplements for children aged 6 to 4. DPT vaccine includes three doses and measles vaccine includes two doses. Malaria treatment is for pregnant women.

Altogether, our results provide convincing evidence in favour of expanding free access to secondary education. Although the study does not alleviate concerns that expansion would need to be accompanied by increased school capacity, it demonstrates that the benefits of free secondary education are likely to justify the necessary investments over time. Further research is necessary to validate the external validity of these findings, in order to assess the impact of this intervention at scale and identify additional ways to maximise its benefits.

Key takeaways for secondary education subsidy policy

There are three key takeaways from this study policymakers should keep in mind when assessing the value of secondary education:

- The potential benefits of subsidised secondary education for girls are sizable and extend to future generations, even in environments without high-quality schooling.

- Education policy is intricately tied to health and family policy.

- Targeting populations in areas with a large male-female enrolment gap, high secondary education drop-out rates, and high infant mortality can increase the impact of school expansion.

References

Blimpo, M P, I Gajigo, and T Pugatch (2016), “Financial constraints and girls’ secondary education: Evidence from school fee elimination in The Gambia,” World Economic Review.

Brudevold-Newman, A (2021), “Expanding access to secondary education: Evidence from a fee reduction and capacity expansion policy in Kenya,” Economics of Education Review.

Duflo, E, P Dupas, and M Kremer (2015), “Education, HIV, and early fertility: Experimental evidence from Kenya,” American Economic Review.

Duflo, E, P Dupas, and M Kremer (2021), “The impact of secondary school subsidies on career trajectories in a dual labor market: Experimental evidence from Ghana,” NBER Working Paper 28937.

Duflo, E, P Dupas, E Spelke, and C Walsh (2024), “Intergenerational impacts of secondary education: Experimental evidence from Ghana,” NBER Working Paper 32742.

Giacobino, C, E Huillery, M Michel, and C Sage (forthcoming), “Schoolgirls, not brides: Education as a shield against child marriage,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics.

Martin, J, L Sprague, E Rose, A Raub, B Bose, P Bhuwania, R Kidman, A Nandi, J R Behrman, and S J Heymann (2023), “The intergenerational effect of tuition-free lower-secondary education on children’s nutritional outcomes in Africa,” Global Public Health.

Grujiters, R (2023), “Free secondary education in African countries is on the rise—but is it the best policy? What the evidence says,” The Conversation.

World Bank (2023), “School enrollment, primary (gross %),” World Bank.