A computer-assisted learning programme in Angola which places teachers at the centre of the learning experience and is tailored to students' needs improved teacher motivation and enhanced the overall classroom experience

Human capital is recognised as crucial for economic growth and human development. This consensus is evident in the global emphasis on achieving universal primary education and the subsequent focus on inclusive and equitable education quality as a key Sustainable Development Goal of the United Nations. Despite efforts to increase school enrollment and attendance, learning outcomes remain low in many developing countries, posing a challenge to improving education quality.

Many programmes have aimed to address this challenge using technology in the schools. However, experimental evidence from various parts of the world indicates that simply providing schools with computers is unlikely to improve children’s academic performance (Escueta et al. 2017), unless combined with a Computer-assisted Learning (CAL) software. CAL software has demonstrated clear positive impacts on student achievement, in particular when individual customisation of contents is possible (Muralidharan et al. 2019).

Important questions do however remain about how to link these CAL programmes to regular teachers and classroom dynamics. In particular, involving teachers could help a variety of outcomes including cognitive skills (Beg et al. 2023) and teachers’ school attendance.

An experimental design within the ProFuturo programme

In 2017 we implemented a randomised field experiment to test the impact of ProFuturo in Luanda, Angola (Cardim et al. 2023).

ProFuturo is one of the largest digital education initiatives in the world: it aims to target 25 million children in vulnerable areas by 2030. Today ProFuturo is present in 45 countries in Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, and Asia, having trained more than 1.4 million teachers and benefited 28 million children.

This programme offers schools a CAL tool that comes with two innovations. First, it places teachers at the center of the learning experience, as they are the ones managing the delivery of the programme in the classroom. This implies significant teacher training. Second, ProFuturo incentivises interaction in the classroom, between teacher and students, as well as between students. The programme includes the distribution of suitcases which include tablets, a computer for the teacher, and a projector. Each suitcase suits roughly one classroom, with sufficient tablets for all students. The programme runs offline. The software contents are interactive and are adapted for different countries in terms of language and cultural references. The contents of the software package include lectures on Language (Portuguese), Mathematics, Science, Technology, as well as Ethics and Citizenship. There are activities available at the end of each module to test students on what they learned. These activities give immediate feedback to students. The platform also allows teachers to have access to the progress of students. Teachers can then customise contents to be used according to the needs of individual students. Before implementation, ProFuturo trains school principals and teachers in the schools where the programme is introduced.

From the 42 primary schools that were selected to receive ProFuturo in Angola, 21 were randomised to receive it in the beginning of 2018 and 21 assigned to start using after 2019. The evaluation measures the impact of utilising ProFuturo during approximately one academic year. After schools were assigned to receive the programme in 2018, the school principals decided on which classes used ProFuturo. As it was recommended by the implementer, the majority of classes selected belonged to grades 4, 5, and 6, i.e., the highest grades of primary education in Angola.

On average, students from classes benefiting from ProFuturo were exposed to the programme about 130 minutes per week. Regarding the content, it is important to note that Science contents were the ones most frequently selected by teachers using the ProFuturo platform. Administrative data provided by the ProFuturo platform reports that 40% of all activities performed using ProFuturo in 2018 in treated schools were in Science, followed by Portuguese (23%) and Mathematics (16%). There was a clear emphasis on group work and active participation of students in classroom activities.

Findings

We find evidence that both students and teachers in ProFuturo schools are more likely to use technology, not only at school, as is the case for teachers during the classes they teach, but also at home, as is the case for students.

ProFuturo was effective at decreasing the absenteeism of teachers and increasing their motivation. The effects on teacher absenteeism are particularly clear, namely when employing administrative data, there were 0.59 standard deviations less days missed by teachers, which represents a 51% reduction. Regarding students, we find that the programme has some effects on increasing their motivation, namely on having a more positive attitude towards Mathematics, but we do not find significant impacts on students’ absenteeism.

We also measure the quality of teachers’ preparation of the classes they teach, their broader time allocation, as well as their behaviour in the classroom. We find higher quality in teachers’ preparation of their classes, which translates into more time devoted to teaching as reported by teachers. From direct observation of classroom activities, we find short-term effects on increasing passive teaching (e.g. monitoring), perhaps as compensation for classes employing ProFuturo teaching. However, these short-term effects do not last and are substituted by positive effects on active teaching, namely through practice and drill, and on improved knowledge of the subject taught.

Our findings on students’ behaviours at home and in school imply positive effects of ProFuturo on time devoted to reading by students and on shared time with their guardians using technology, possibly playing games. They are also suggestive that ProFuturo induces some movement towards pro-social interaction between students.

Finally, we find a positive treatment effect on the standardised test scores in Science. We do not find any significant effects on other subjects. Teachers report higher levels of knowledge in Science, which is consistent with higher test scores by students in that subject. This may be explained by the fact that this is the subject most frequently selected in classes employing Profuturo.

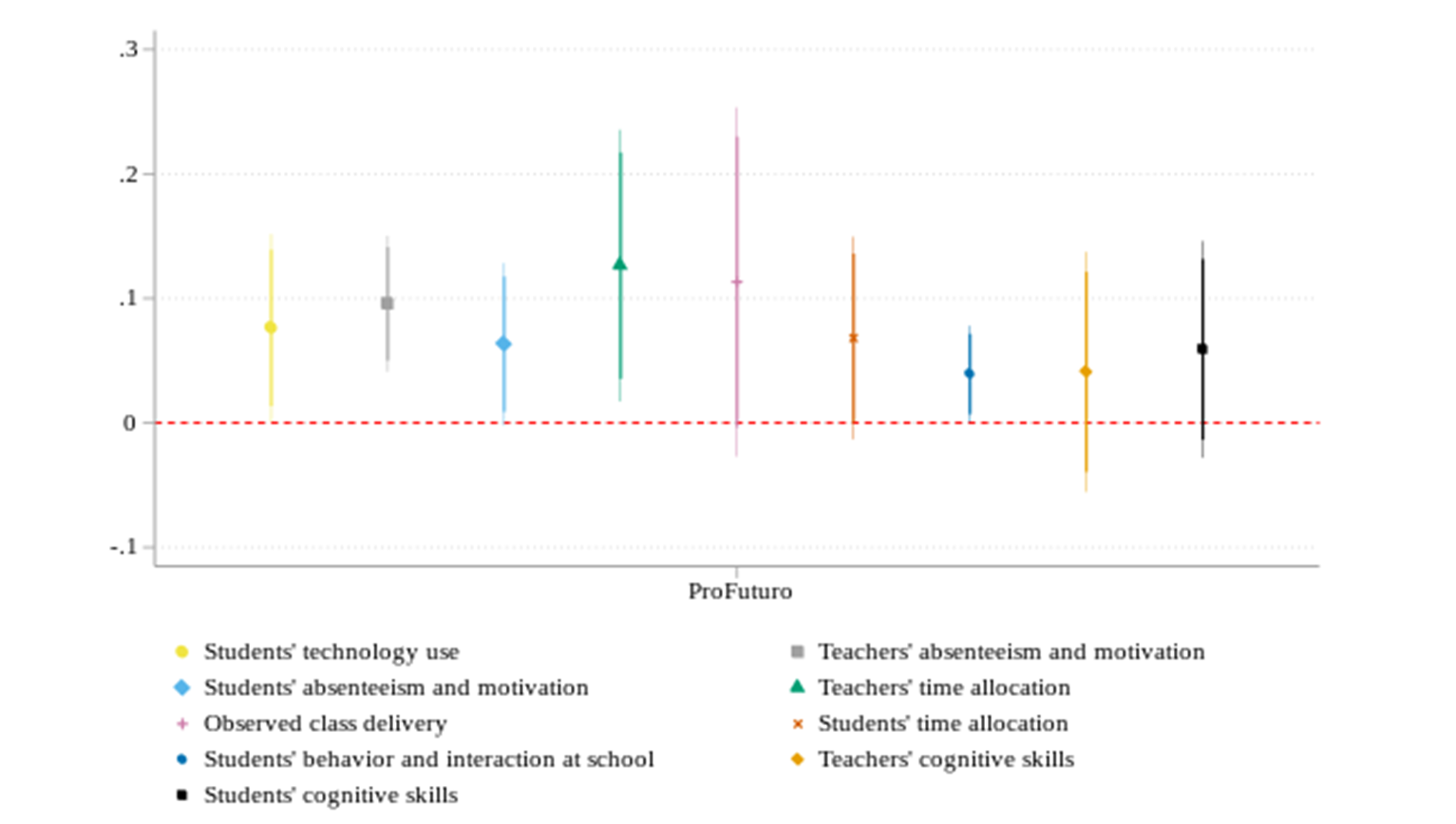

Figure 1 shows treatment effects on aggregate indices of outcomes at the school level.

Key takeaways

Overall, our findings show that despite the short time window of our programme evaluation, in some cases of less than one year from the beginning of treatment to endline measurements, and a relatively low intensity of weekly exposure to the programme, we are able to identify some encouraging findings.

First, we observe direct effects on familiarity with technology by both teachers and students. Second, we report on increased motivation of teachers, illustrated by a clear decrease on the number of days teachers missed school. Some evidence suggests that teachers improved class preparation and active classroom teaching, while students became more interested in reading at home and engaged in more altruistic interactions at school. Although we do not find significant impacts on test scores in Portuguese or Mathematics, we find positive effects of ProFuturo on students’ test scores for Science, which was the subject most frequently selected under the ProFuturo platform in our setting.

We estimate that the cost of increasing student’s test score (Science) by 0.1 standard deviation is USD 10 per student. This cost estimate per student places the ProFuturo programme in the lower half (McEwan 2015) and close to the median in terms of cost-effectiveness (McEwan 2015, Mbiti et al. 2019) of comparable interventions in schools of developing countries.

References

Beg, S, A Lucas, and U Saif (2023), “Engaging with teachers unlocks the potential of technology in schools: Evidence from Pakistan”, VoxDev.

Cardim, J, T Molina-Millán, and P C Vicente (2023), “Can technology improve the classroom experience in primary education? An African experiment on a worldwide program.” Journal of Development Economics 164: 103145.

Escueta, M, V Quan, A J Nickow, and P Oreopoulos (2017), “Education technology: An evidence-based review.” Technical Report, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Mbiti, I, K Muralidharan, M Romero, Y Schipper, C Manda, and R Rajani (2019), “Inputs, incentives, and complementarities in education: Experimental evidence from Tanzania.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 134(3): 1627–1673.

McEwan, P J (2015), “Improving learning in primary schools of developing countries: A meta-analysis of randomized experiments.” Review of educational research 85(3): 353-394.

Muralidharan, K, A Singh and A J Ganimian (2019), “Disrupting education? Experimental evidence on technology-aided instruction in India.” American Economic Review 109(4): 1426–1460.