Paying landowners to conserve their forested land is a leading approach to prevent deforestation. Evidence from Mexico shows that smarter contract design can more than quadruple cost-effectiveness.

Deforestation is a major source of the carbon emissions which drive climate change, and a cause of rapid biodiversity loss (Giam 2017). Today, deforestation rates are highest in developing countries. Often it occurs when households clear forest land they own to expand their farming activity or earn money by selling timber. Banning these families from deforesting would be beneficial for the planet but would deprive them of crucial income.

The importance of ‘Payments for Ecosystem Services’

Consequently, Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) has emerged as a key conservation policy in which landowners are offered payments in exchange for natural resources management activities such as forest protection (Brouwer et al. 2017). The payments offset the income that households forgo to keep their forest intact and because participation is voluntary, households in developing countries are not being asked to make an economic sacrifice for the sake of climate change mitigation.

However, a challenge with PES and, in fact, any financial incentive programme, is that some participants are paid for behaviour they would have undertaken even without an incentive. A PES programme’s benefits accrue when people undertake new conservation because of the programme, but this is only a subset of the conservation that occurs and is rewarded. If so-called “inframarginal payments” – payments for forest that would have been conserved anyway - are extensive, PES becomes a cost-ineffective way to protect forests.

Several studies have evaluated how much additional forest cover is generated by PES programmes (Alix-Garcia and Wolff 2014, Salzman et al. 2018). One of the most effective PES programmes that has been documented took place in Uganda (Jayachandran et al. 2017). One way the Uganda PES contract differed from standard practice in PES is that if a household participated, they had to enrol all the forest they owned.

In contrast, in most PES programmes, participants are allowed to choose which parcels of land to enrol in the programme. Savvy participants will enrol the parcels of land that they would have conserved anyway, leaving parcels they want to deforest out of the programme. If that occurs, many PES payments will be inframarginal.

Requiring full enrolment in a PES programme reduces landowners’ ability to enrol only those parcels they were already going to conserve

In a recent study, we tested how requiring participants to enrol all their forest – which we call “full enrolment” – changes the effectiveness of PES, using a randomised controlled trial in Chiapas, Mexico (Izquierdo-Tort et al. 2024). Study participants were randomly offered either a PES contract requiring full enrolment or a contract that allowed them to enrol the subset of their land of their choosing (“standard contract”). Mexico’s national PES programme, Pago Por Servicios Ambientales (PSA) uses the standard contract and research has documented high rates of deforestation on parcels that participants leave out of PSA (Izquierdo-Tort 2019).

In 2021, working in five communities, we contacted households that had applied to PSA but whose applications were turned down due to the programme’s limited funding. We mapped the landholdings of all of those interested in participating in the study. The average landholding was about 40 hectares, half of it forest cover. We also had access to the participants’ recent PSA applications, so we knew which subset of their land they would enrol if given the option to choose.

Then our implementation partner, Natura y Ecosistemas Mexicanos (Natura Mexicana), offered each participant the randomly assigned contract – either full enrolment, which covered all their landholdings, or the standard contract, which covered the parcels they submitted in their PSA application. The contract was for one year and paid at the same annual rate as PSA, MX $1000 (about US$50) per hectare.

The main goal of our study was to assess whether the two contract types lead to different amounts of deforestation. We measured forest cover using a remote-sensing based measure that we constructed by applying machine learning methods to Planet satellite imagery. We also combined the forest cover measure with administrative data on the payments made to assess cost-effectiveness, or hectares conserved per dollar spent.

How did adjusted contracts impact deforestation?

The study results were stark:

- As expected, full enrolment led to lower compliance with the contract terms (71% compliance in the full enrolment arm versus 91% in the standard contract arm). The provision made the programme requirements more stringent, so fewer people met them.

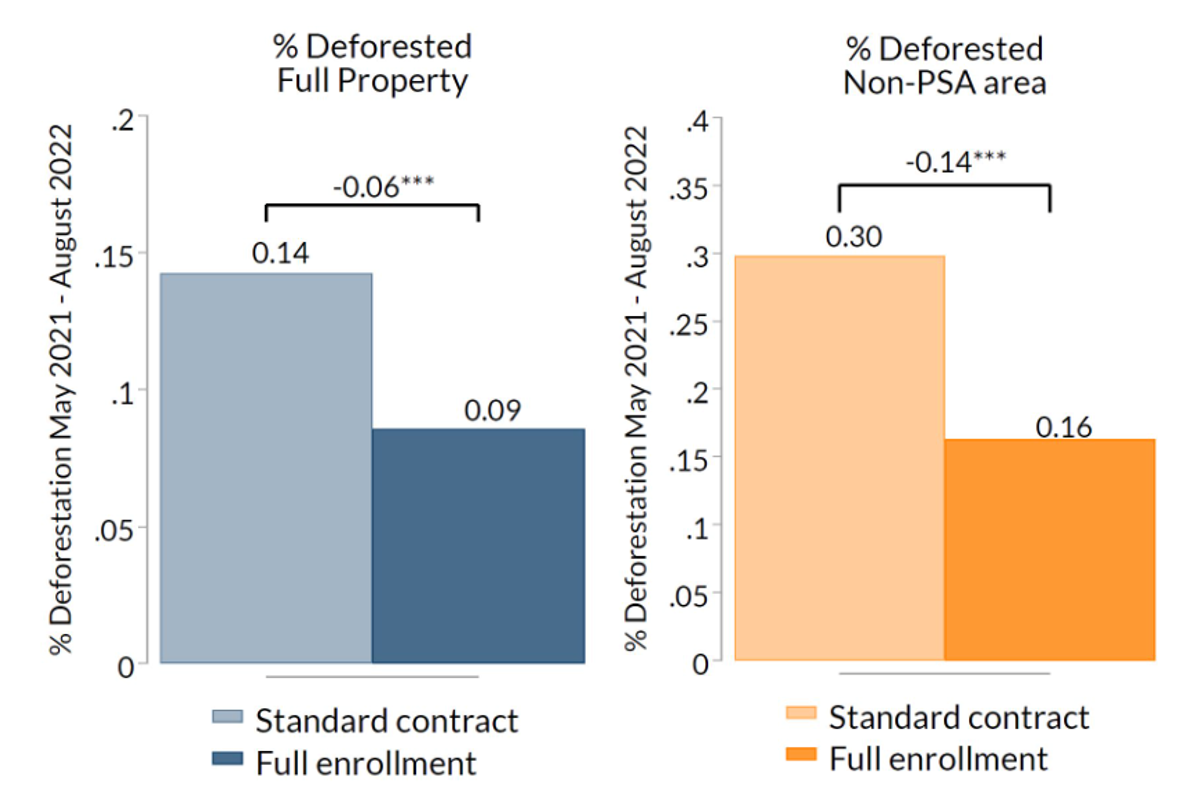

- Despite lower compliance, full enrolment led to a 41% decrease in total deforestation compared to standard PES (Figure 1a). This was driven entirely by increased conservation of parcels that would not have been enrolled under a standard PES contract (Figure 1b).

- Full enrolment was 4.8x as cost-effective, meaning it led to 4.8 times as many hectares of avoided deforestation per dollar spent as the standard contract did. (The study did not include a pure control group, so we use prior studies of PSA to assess the effectiveness of the standard contract, relative to no PES programme existing.)

- The cost of averted carbon through full enrolment PES is US$4.76 per metric ton, well below current average net carbon prices globally (World Bank 2024).

Figure 1 (a,b) (Izquierdo-Tort, Jayachandran and Saavedra 2024)

Environmental budgets can achieve a lot more environmental protection via smarter contract design

Given growing concerns about effectiveness and equity in environmental protection policies, there is a strong case for giving landholders in developing countries some room for maneuver when engaging with programmes like PES. Yet, all freedom of choice is not equivalent. Landowners should be given the choice of whether to participate in a PES programme so that conservation efforts do not exacerbate poverty. However, letting them choose which subset of their forest to enrol is a give-away to them that undermines the cost-effectiveness of PES.

Making forest protection more cost-effective is important in the context of PSA, which saw a 70% budget cut between 2015 and 2019. Moreover, globally there is limited funding for climate change mitigation. Using smarter contract design to achieve greater cost-effectiveness could help the world achieve more conservation even without increased funding.

Thanks to Natura y Ecosistemas Mexicanos, A.C. and Innovations for Poverty Action for collaboration on the project. This project was funded by the King Climate Action Initiative at J-PAL.

References

Alix-Garcia and Wolff (2014), “Payment for Ecosystem Services from Forests”, Annual Review of Resource Economics. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-resource-100913-012524

Audy, De Latt, Jayachandran, Lambin, Stanton, and Thomas (2017), “Cash for carbon: A randomized trial of payments for ecosystem services to reduce”, Science. Available at: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aan0568

Bennett, Carroll, Goldstein, Jenkins, and Salzman (2018), “The global status and trends of Payments for Ecosystem Services”, Nature. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-018-0033-0

Brown, Harris, Morel, and Saatchi (2011), “Benchmark map of forest carbon stocks in tropical regions across three continents”, PNAS. Available at: https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1019576108

Brouwer, Engel, Ezzine-de-Blas, Muradin, Pascual, Pinto, and Wunder (2018). “From principles to practice in paying for nature’s services”, Nature Sustainability. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-018-0036-x

Giam (2017), “Global biodiversity loss from tropical deforestation”, PNAS. Available at: https://www.pnas.org/doi/abs/10.1073/pnas.1706264114

Izquierdo-Tort, Ortiz-Rosas, and & Vázquez-Cisneros (2019), “‘Partial’ participation in payments for environmental services (pes): Land enrolment and forest loss in the Mexican Lacandona rainforest”, Land Use Policy 87. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0264837718316788

Izquierdo-Tort (2020), “Payments for ecosystem services and conditional cash transfers in a policy mix: Microlevel interactions in Selva Lacandona, Mexico”, Environmental Policy and Governance. Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/eet.1876

Izquierdo-Tort, Jayachandran, and Saavedra (2024), “Redesigning payments for ecosystem services to increase cost-effectiveness”, Nature Communications. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-024-53643-1

World Bank (2024), “State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2024”. Available at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/b0d66765-299c-4fb8-921f-61f6bb979087