Households in Bangladesh hold inaccurate beliefs about indoor air pollution and the effectiveness of air purifiers. Correcting both beliefs is necessary to increase the adoption and use of air purifiers.

High levels of ambient air pollution impose severe economic and welfare costs, especially in low-income countries (Oliva et al. 2019). Over five million people die annually from exposure to ambient air pollution, with South Asia alone accounting for 1.4 million deaths per year (GBD Risk Factors 2024). Despite persistently high pollution levels, the demand for private preventive technologies like air purifiers remains remarkably low (Greenstone et al. 2021, Greenstone and Jack 2015) - even among households that can afford them. For instance, fewer than 1% of middle-class households we contacted in Dhaka, Bangladesh - which is consistently ranked as one of the cities with the worst air pollution in the world (IQAir 2024) - own an air purifier.

Why don’t households, for whom air purifiers are affordable, adopt them despite extremely high ambient air pollution levels?

In Chowdhury et al. (2024), we show that households hold incorrect beliefs about the severity of indoor air pollution and the effectiveness of air purifiers - correcting both misconceptions is necessary to increase the adoption and use of air purifiers.

Fact 1: Households have inaccurate beliefs about indoor air pollution

First, using indoor air pollution monitors we installed in households, we show that during the winter months, pollution is staggeringly high, with an hourly average of 133 µg/m3, which is 9 times higher than the WHO's 24-hour average guideline of 15 µg/m3. However, while 76% of households believe that the ambient air in their area is severely polluted, they greatly underestimate the severity of indoor pollution, with the same percentage reporting that the air in their homes is only minimally to moderately polluted.

Fact 2: Households have inaccurate beliefs about air purifier effectiveness

Second, we find that households are uncertain about, and significantly underestimate, the effectiveness of air purifiers in removing indoor pollution. Fewer than half of the households had an opinion on purifier effectiveness, and less than a third believed that purifiers removed more than 25% of air pollution from the rooms where they were used, which contrasts sharply with the actual effectiveness of air purifiers - 80% in real-world household environments (Lu et al. 2024).

Overall, households have an extremely low willingness to pay (WTP) for air purifiers; the average household WTP was US$12.2, or 8.4% of the retail cost of air purifiers (US$150 or BDT 17,000).

Research design to correct misperceptions

To correct these misconceptions, we conducted a multi-phase field experiment providing air monitors and purifiers to households.

Phase 1: Household recruitment, baseline survey, and randomised assignment of indoor air pollution monitors in November 2023

In November 2023, we recruited 1,008 households from three large housing associations. Eligibility required a functioning WiFi connection and no existing air purifier - criteria met by 99% of interested households. These are middle-income households with an average annual household income above US$6,000 (Munir et al. 2015); 34% own an air conditioner, which costs at least twice as much as an air purifier and consumes substantially more electricity.

Immediately following recruitment, in November, we conducted a short Phase 1 survey on perceptions of indoor and outdoor air quality.

Then, 512 randomly selected households received an air quality monitor displaying real-time PM2.5 levels along with a chart that categorised these levels from “good” to “hazardous.” These monitors recorded and transmitted minute-by-minute data on indoor PM2.5 levels.

Phase 2: Midline survey and randomised assignment of indoor air purifiers in January 2024

In January 2024, two months later, we conducted the Phase 2 survey, gathering information on household beliefs about outdoor air pollution, indoor air pollution, and air purifiers' benefits. We used a modified Becker-DeGroot-Marschak (BDM) mechanism to elicit households' willingness to pay for air purifiers. Before the elicitation, we informed households that air purifiers remove indoor air pollution.

Subsequently, we randomly provided 345 households with a free air purifier. Each purifier was connected to a WiFi-enabled smart plug, allowing us to collect minute-by-minute usage data. We further randomly assigned these purifier-owning households to receive either no electricity compensation, compensation paid daily, or compensation paid monthly.

Phase 3: Endline survey in March 2024

In March 2024, we conducted the Phase 3 survey, collecting endline data on perceptions of air purifier benefits, households' willingness to pay for an additional purifier, and their willingness to accept cash to sell back their existing purifiers.

We report three sets of findings:

Result 1: Access to monitors corrects beliefs about indoor air pollution but fails to increase demand for air purifiers

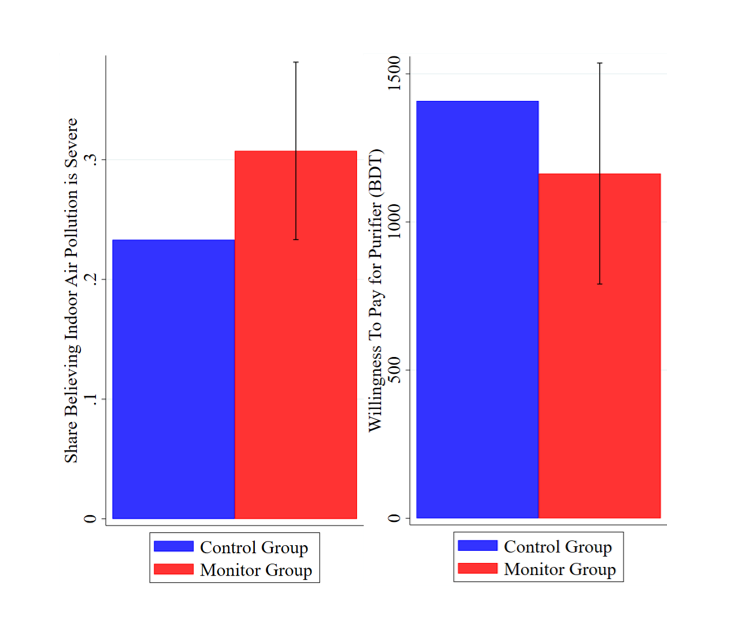

First, providing households with air pollution monitors has a large and statistically significant effect on correcting their perceptions of indoor air pollution and its health risks to adults and children (Figure 1). Households that received monitors were 7.4 percentage points more likely to believe that the air in their homes was severely polluted - a 32% increase compared to households without monitors. However, access to air quality monitors did not increase households' willingness to pay for an air purifier, even though they were informed about its purpose in removing indoor air pollution before elicitation.

Figure 1: Effect of monitors on air pollution beliefs and purifier WTP

Result 2: Experience with purifiers corrects beliefs about their effectiveness but households rarely use them

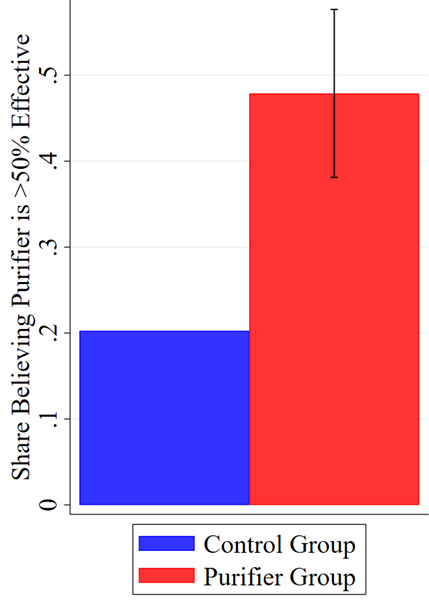

Second, although providing air purifiers corrected misperceptions about their effectiveness (Figure 2), households did not seem to value the devices, as they rarely used them - even when we compensated them for the electricity costs of operating them. Specifically, even with compensation, nearly two out of three households used the air purifier for less than 30 minutes per day (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Effect of purifiers on purifier effectiveness beliefs

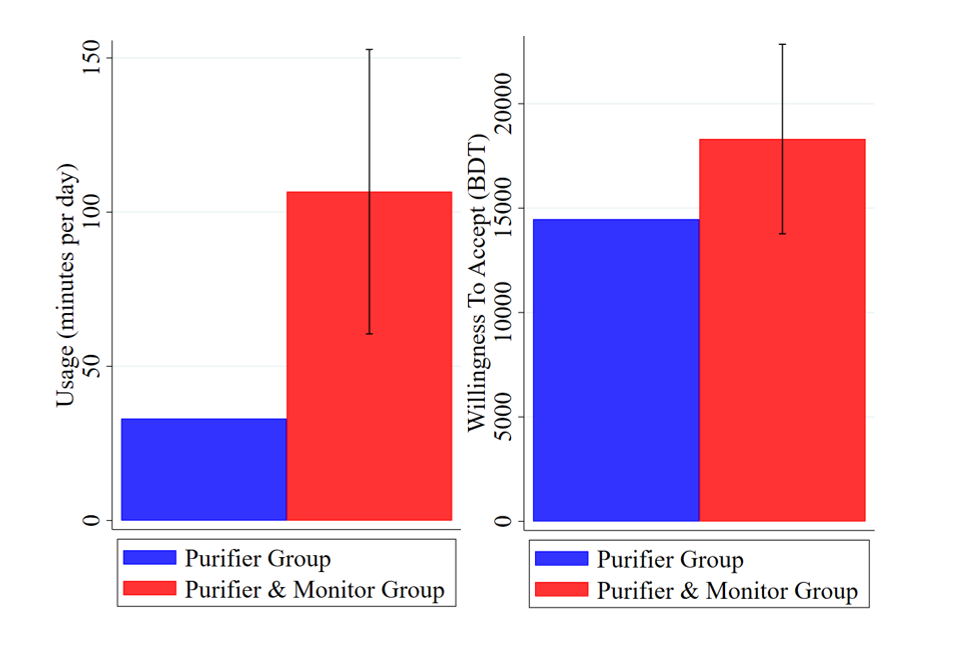

Result 3: Access to both monitors and purifiers increases usage and households’ valuation of purifiers

Third, we show that providing households with both monitors and purifiers increases both air purifier use and the valuation of the purifier relative to households that only receive a purifier (Figure 3). Data from smart plugs indicate that monitors increased purifier use by 270%, equivalent to an additional 74 minutes per day.

Moreover, households that received both monitors and purifiers increased the price they were willing to accept to sell back the air purifiers by BDT 3,800 ($32), a 26% increase, compared to households that received only the purifier. Lastly, households provided with both a monitor and a purifier increased their WTP between Phase 2 and Phase 3 for a second purifier by 52.7%, although this estimate is underpowered. In contrast, households that received only a purifier saw a much smaller and statistically insignificant 11.7% increase in WTP for a second purifier. Similarly, households that received only a monitor exhibited a small and statistically insignificant 8.1% increase in WTP for the first air purifier.

Figure 3: Effect of monitors and purifiers on purifier usage and valuation

Why are preventive technologies not used for air pollution?

Our results help reconcile seemingly disparate findings about the under adoption of preventive health technologies against ambient air pollution. When individuals have accurate beliefs about the effectiveness of a preventive health technology - such as face masks in South Asia - but lack a full understanding of the severity of the underlying health risk, providing information about the risk can lead to increased adoption of the technology (Baylis et al. 2024, Ahmad et al. 2023). Conversely, when people are familiar with the effectiveness of the preventive measure - like air purifiers in China - simply informing them about the severity of the health risk may be sufficient to boost adoption (Ito and Zhang 2020, Barwick et al. 2024). However, if individuals lack accurate beliefs about both the underlying health risk and the effectiveness of the preventive measure - as is the case with air purifiers in South Asia - correcting beliefs about only one of these factors will not increase adoption (Greenstone et al. 2021). Therefore, to shift from an equilibrium with incorrect perceptions to one with correct perceptions, a sufficient number of households must change their beliefs about both the health risk and the effectiveness of the preventive measure.

References

AQLI (2023), “The Air Quality Life Index.”

Ahmad, H F, M Gibson, F Nadeem, S Nasim, and A Rezaee (2023), “Forecasts: Consumption, production, and behavioral responses,” Mimeo.

Barwick, P J, S Li, L Lin, and E Y Zou (2024), “From fog to smog: The value of pollution information,” American Economic Review, 114(5): 1338–1381.

Baylis, P M, K Greenstone, K Lee, and H Sahai (2024), “Is the demand for clean air too low? Experimental evidence from Delhi,” Mimeo.

Chowdhury, A, T Garg, M Jagnani, and M Mattsson (2024), “Dual misbeliefs and preventive technology adoption and use: Evidence from air purifiers in Bangladesh,” Mimeo.

GBD Risk Factors (2024), “Global burden and strength of evidence for 88 risk factors in 204 countries and 811 subnational locations, 1990-2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021,” Lancet (London, England), 403(10440): 2162–2203.

Greenstone, M, and B K Jack (2015), “Envirodevonomics: A research agenda for an emerging field,” Journal of Economic Literature, 53(1): 5–42.

Greenstone, M, K Lee, and H Sahai (2021), “Indoor air quality, information, and socioeconomic status: Evidence from Delhi,” AEA Papers and Proceedings, 111.

IQAir (2024), “World's most polluted cities, 2017-2023,” Accessed on 19 September 2024. Available at: https://www.iqair.com/sg/world-most-polluted-cities?srsltid=AfmBOopc6dqbGQGOf6VqMLr6bmRlGKbClVSnpEvl7uLXSr492dHIQm-E.

Ito, K, and S Zhang (2020), “Willingness to pay for clean air: Evidence from air purifier markets in China,” Journal of Political Economy, 128(5): 1627–1672.

Lu, F T, et al. (2024), “Real-world effectiveness of portable air cleaners in reducing home particulate matter concentrations,” Aerosol and Air Quality Research, 24(1).

Munir, Z, O Muehlstein, and V Nauhbar (2015), “Bangladesh: The surging consumer market nobody saw coming,” Boston Consulting Group. Available at: https://www.bcg.com/publications/2015/bangladesh-the-surging-consumer-market-nobody-saw-coming.

Oliva, P, M Alexianu, and R Nasir (2019), “Suffocating prosperity: Air pollution and economic growth in developing countries,” International Growth Centre: Growth Brief.

World Health Organisation (2019), “Air pollution,” 4(18).