The National Greening Program, a large-scale tree planting programme in the Philippines, not only contributes to carbon sequestration but also promotes poverty reduction and job creation.

Addressing dual global challenges of climate change and poverty

The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals emphasise that ecosystem services and biodiversity conservation are essential to human well-being and have thus defined a dual agenda where development targets for people and planet sit alongside each other in a unifying framework (United Nations 2015). As countries around the world seek solutions to both climate change and poverty, nature-based solutions, such as tree planting programmes, are gaining attention. These programmes offer the potential to not only sequester carbon, but also create jobs and transfer productive forestry assets to receiving individuals or communities, aligning environmental and development targets.

In our research (Pagel and Sileci 2024), we explore whether tree planting can be used as a poverty alleviation instrument by studying the Philippines’ National Greening Program (NGP), a large-scale tree planting initiative. We conduct a nationwide evaluation linking NGP tree planting projects with two granular development indicators: official small area poverty estimates and a novel measure of extreme poverty based on the proportion of built settlements associated with no nighttime luminosity, extending work by McCallum et al. (2022) to a panel setting. We find that treated municipalities experience a decrease in poverty of 6 percentage points and a decrease in the share of unlit settlements of 8 percentage points.

The National Greening Program: A policy for climate and poverty

Launched in 2011, the NGP is primarily a reforestation initiative aimed at planting 1.5 billion trees across 1.5 million hectares and increasing forest cover by 11.4% from the 13.2 million hectares of natural forest recorded in 2010 (Global Forest Watch 2023). However, the programme is designed to achieve more than just reforestation and carbon sequestration. The NGP pays local organisations for three years for seedling production, site preparation, and maintenance. After a three-year period dedicated to the establishment of the plantation, the local organisation assumes full managerial control of the plantation assets and retains all generated proceeds.

From 2011 – 2016, with a budget of over $700m, the NGP implemented 80,522 localised projects across the Philippines, planted hundreds of thousands of hectares, generated hundreds of thousands of jobs, and empowered local communities. Figure 1 shows that the majority of the tree planting sites were agroforestry or reforestation.

Figure 1: Classification of tree planting sites

Key findings: Positive socioeconomic and environmental impacts of the National Greening Program

To assess the impact the NGP has on socioeconomic outcomes, we implement a dynamic difference-in-differences identification strategy that compares the pre-planting and post-planting periods between earlier treated NGP municipalities and a pool of municipalities who have either ‘not-yet’ been treated by the time of the programme implementation, or are never treated throughout the duration of the panel. Figure 2 presents a map illustrating the phase-in design for when municipalities received the NGP.

Figure 2: NGP timing of treatment pool

Next, figure 3 presents the main results from our research. It shows that municipalities that participated in the programme experienced a 6 percentage point reduction in poverty (Top) and an 8 percentage point reduction in the share of unlit settlements (Bottom). Both figures illustrate the persistence of the estimated effects, with statistical significance preserved up to 7 years after the NGP roll-out and without any reversal towards zero in terms of levels.

Figure 3: Impact of NGP on socio-economic measures

Spillover effects: Regional and local economic benefits of the National Greening Program

The net impact of a forest policy encompasses effects within the spatial unit boundary, as well as spillover effects outside, referred to as policy-induced leakage effects (Börner et al. 2020). To understand whether the NGP led to economic spillovers into surrounding villages, we take advantage of the high-resolution village level data. We exploit 32,472 control villages and compare villages that have a neighbour who is treated earlier by the NGP to a pool of villages who have ‘not-yet’ had a neighbour treated by the time of the treatment, or to control villages that never have a neighbour treated by the NGP.

We find evidence of spillovers, with neighbouring control villages experiencing a 4.5 percentage point reduction in the share of unlit settlements when a neighbour receives the tree planting programme relative to control villages who do not have a treated neighbour.

Suggestive evidence that the National Greening Program led to structural transformation

We then analyse whether the NGP had broader sectoral changes in the distribution of employment and labour supply as two forms of structural change. We first show that the NGP spurred structural shifts in employment, reducing agricultural employment by 3.8%, while boosting jobs in unskilled labor by 5.6% and services by 2.6%.

Additionally, we find no evidence that the NGP led to changes in the labour supply through either population growth or migration. Taken together, this provides evidence that the tree planting programme itself generated economic activity rather than economic activity being spurred on by changes in the labour supply or inducing migration.

Environmental gains: More than just carbon

In total, we estimate that the NGP sequestered was between 71.4 - 303 MtCO2 over 10 years. Using the lower bound estimate, this is equivalent to the greenhouse gas emissions from 16,993,330 gasoline-powered passenger vehicles driven in one year or the CO2 emissions from 18.4 coal-fired power plants in one year. For policymakers focused solely on reducing carbon emissions, we then calculate the cost per ton of carbon abated, finding that the NGP lowers CO2 emissions at a cost between $2 and $10 per ton.

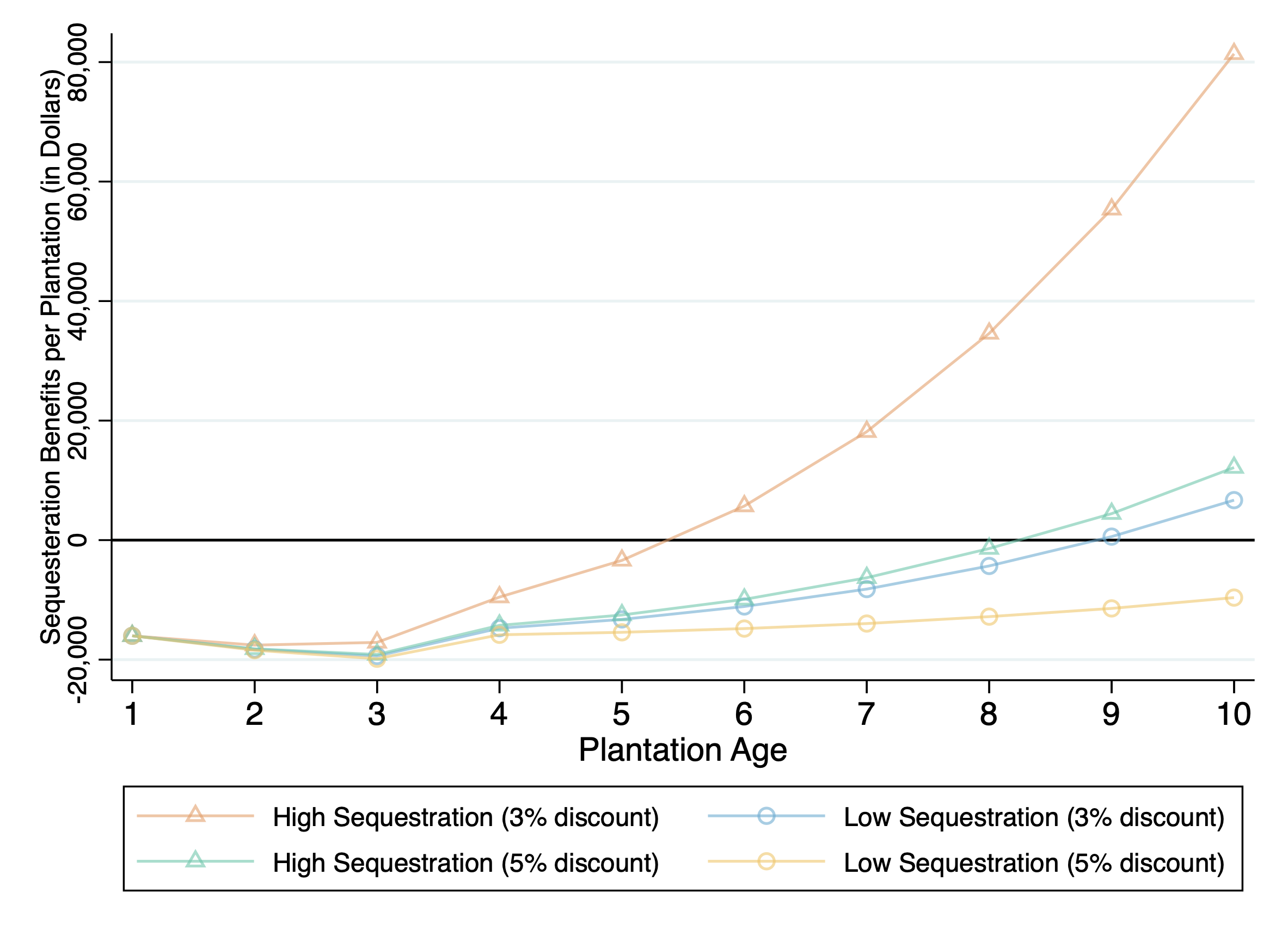

Lastly, we estimate that the NGP sequestered CO2 was valued between $163 million and $9.57 billion and find at the plantation level (Figure 4) that the average sequestration benefits surpass the implementation costs between years 6 and 9.

Figure 4: Carbon sequestration benefits per plantation

Policy implications: Designing effective multi-objective programmes

The success of the NGP demonstrates the potential of nature-based solutions to address both environmental and socioeconomic challenges. However, the programme's design elements were crucial to its success. Payments to local communities, structured over several years, and managerial control created long-term incentives for plantation maintenance and care. Additionally, the transfer of tree plantation assets to local organisations ensured that the economic benefits of the programme were sustained beyond the initial planting phase.

Policymakers in other countries can learn from the NGP’s experience. First, ensuring high survival rates for planted trees was a critical hurdle. While the NGP achieved an average survival rate of 83%, maintaining this level required continuous monitoring and support from both government extension officers and local organisations. Second, tree planting programmes, when designed with strong community involvement and financial incentives, can achieve multiple objectives. Importantly, such programmes should not be viewed solely as environmental interventions but as comprehensive development strategies that can generate lasting economic and social benefits.

Conclusion: Scaling up nature-based solutions

The Philippines’ National Greening Program offers a compelling example of how tree planting can contribute to both climate mitigation and poverty alleviation. By sequestering carbon at a low cost and creating economic opportunities for poor communities, the NGP shows that nature-based solutions can be an effective tool for achieving sustainable development.

As countries look to scale up their climate actions in the coming years, programmes like the NGP should be considered not only for their environmental benefits but also for their potential to drive economic transformation and reduce poverty. Integrating these dual goals into future policies will be essential for addressing the interconnected challenges of climate change and development.

References

Börner, J, D Schulz, S Wunder, and A Pfaff (2020), “The effectiveness of forest conservation policies and programs,” Annual Review of Resource Economics, 12: 45–64.

Global Forest Watch (2023), “Tree cover loss in the Philippines,” GFW. Accessed on 11/04/2023 from www.globalforestwatch.org.

McCallum, I, C C M Kyba, J C L Bayas, E Moltchanova, M Cooper, J C Cuaresma, and S Fritz (2022), “Estimating global economic well-being with unlit settlements,” Nature Communications, 13(1): 2459.

Pagel, J, and L Sileci (2024), “More than just carbon: The socioeconomic co-benefits of large-scale tree planting,” Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment Working Paper No. 410.

United Nations (2015), Sustainable Development Goals.