Evidence from Taliban-controlled Afghanistan shows that digital aid is a cost-effective, credible, and efficient way to reach vulnerable populations, in this case poor, tech-illiterate, female-headed households, in fragile states.

Many contemporary food crises, including those in Sudan, Myanmar, Somalia, Northern Nigeria, Yemen, and Taliban-controlled Afghanistan (the focus of our study), are marked by conflict, instability, repression of vulnerable groups, and fears that aid could be misappropriated by hostile actors. These cases reflect a tragic global trend: humanitarian aid needs are at their highest since 1945 (FCDO 2023). And aid budgets are failing to keep pace. Between 2018 and 2021, humanitarian food security budgets fell 40% in relative terms, from US$85 per person in 2018 to $51 per person (Food Security Information Network 2023). Growing needs and falling budgets raise the importance of cost-effectiveness.

Hunger is also concentrating in fragile and conflict-affected states. In such settings, where oppressive actors control resource flows and restrict access to vulnerable populations, humanitarians face a dilemma: deliver aid and risk supporting hostile actors and fuelling conflict (Nunn and Qian 2014) or halt aid despite acute need. This only compounds the severe logistical challenges in these countries.

The promise of digital humanitarian aid

Delivering assistance as digital aid - assistance provided through digital payments rather than as physical cash or food - presents a potential solution. Many development programmes have used digital payments to alleviate poverty (Muralidharan et al. 2016, Suri et al. 2023). Digital aid can have significant advantages relative to the status quo options of in-kind food aid or physical cash payments, including scalable technology and the integration of private firms on a common platform to reduce delivery costs. From the beneficiary's perspective, digital payments also reduce coordination costs and delays, utilise local supply chains, and increase privacy including from local authorities (Byrd 2023), a valuable feature in fragile states with oppressive regimes.

However, there is limited empirical evidence of the efficacy of digital payments in providing immediate humanitarian relief during the type of crises that are increasingly common in fragile states. This knowledge gap may increase reluctance to adopt potentially useful but untested technologies, especially in countries facing conflict, high food insecurity, and active governmental oppression. To explore this, we surveyed experts prior to the release of our results about the anticipated impacts of our study. They predicted that only 43% of the intended beneficiaries would be able to use the digital aid and that 40% of beneficiaries would report attempts to tax or divert the payments. Are their predictions accurate? Can digital aid be accessed and used by tech-illiterate households? Can it deliver immediate humanitarian relief to vulnerable, hard-to-reach populations? And can it help reduce diversion by hostile actors? Our study (Callen et al. 2024) aims to answer these questions.

The humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan and our intervention

We conducted a randomised controlled trial in Taliban-controlled Afghanistan from November 2022 to February 2023. Afghanistan was then, and still is, in a deep humanitarian crisis. In 2021, the Taliban seized control of the government. Following this, the country experienced a severe economic collapse. The GDP of Afghanistan contracted by 30-35%, and Afghan citizens have since been at an ongoing risk of famine. In 2024, 23.3 million people in Afghanistan are in urgent need of humanitarian aid, with more than half of them being children (UNICEF 2024). In 2022, the Taliban banned women from NGO work, drastically reducing aid to women and children, with 94% of NGOs halting or scaling back services (UN Women 2023). In August 2024, the Taliban reinforced their commitment to gender apartheid by issuing a decree mandating that women must veil in front of male strangers, are prohibited from singing or reading in public, and are barred from interacting with or even looking at men not related by blood or marriage. In this context, we experimentally evaluated a digital aid programme developed in partnership with community, nonprofit and private organisations. The intervention transferred digital value vouchers to beneficiaries' mobile phones through HesabPay, an Afghan digital payment platform. These were redeemable at any of HesabPay's network of enrolled local merchants. We collaborated with locally elected Community Development Councils (CDCs) in Kabul, Herat, and Mazar--i-Sharif to identify a sample of 2,409 poor, tech-illiterate, female-headed households. None of our participants had smartphones or experience with digital payment platforms. To help with this, we conducted onboarding sessions to help each woman open an account with HesabPay and complete a test purchase with a nearby merchant.

We then randomly assigned 1,208 households to the "early" group (treatment), each receiving a digital aid transfer of USD 45 (4,000 AFN) every two weeks for two months from November 6 to December 31, 2022. The remaining 1,201 households formed the "late" group (control), receiving the same aid from January 1 to February 28, 2023. We compare the outcomes of the two groups during the two months in which only the early group was receiving digital aid to assess the impact of the humanitarian assistance. This is a setting where consumption smoothing is not feasible, with our sample being severely credit-constrained (only 0.29% of the sample indicated they could borrow). This ensures that any differences between the treatment and control groups can be attributed to our intervention and not due to any consumption-smoothing behaviour by the households.

Figure 1: Interventions and results

The impact of digital humanitarian aid in Afghanistan

The study has four key findings. First, tech-illiterate women can use digital transfers. Almost all of them (99.75%) used these payments and 20.9% used them across multiple merchants indicating that the beneficiaries understood that they could use any participating merchant. At the end of the study, 80% of them also preferred them over the costlier “aid as cash” option in a hypothetical exercise. These results are striking in this context, where our sample has low-education levels (63.3% are unschooled) and no experience with mobile money.

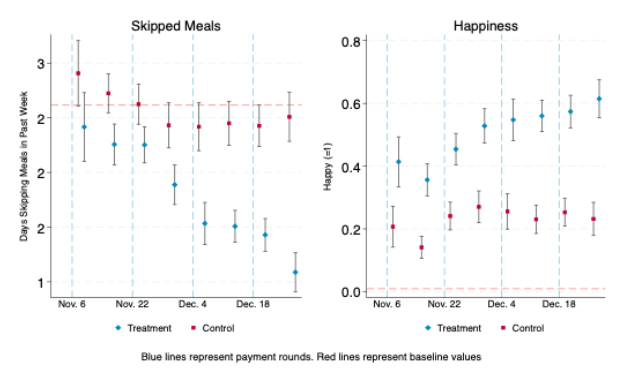

Second, digital aid improves food security and nutrition. Beneficiaries skipped meals 0.76 fewer days per week. Children were 11.7 percentage points less likely to skip meals over the past week. The percentage of households where everyone ate regularly increased by 9.3 percentage points. Beneficiaries reduced meals of only bread and tea by 1.61 meals each week. It also led to more diverse diets.

Figure 2: Effect on skipped meals and happiness over the entire programme

Third, digital aid improves mental well-being. The treated group was 33.5 percentage points more likely to report an improvement in their economic situation, compared to a base of just 4.8% in the control group. The treated group was also 28 percentage points more likely to be very or quite happy, relative to the control group. Overall, our index of prespecified mental wellbeing measures improved by 1.5 standard deviations, although from a very low base. These results are meaningful in a setting like Afghanistan, which has consistently ranked as the country with the lowest levels of happiness since the Taliban takeover in 2021 (Gallup 2024).

Fourth, digital aid was not diverted by local authorities. We rigorously checked every point of potential leakage:

- The beneficiaries were selected without interference from the Taliban.

- The digital payment platform automatically cross-checked beneficiary names with sanctions lists to prevent funds from reaching hostile actors.

- Surveys confirmed that neither the beneficiaries nor the merchants were taxed in either cash or kind.

- Utilisation of a blockchain algorithm allowed for records of all transactions on an immutable ledger, enabling tracking and transparency.

Delivering humanitarian aid digitally in fragile contexts – policy implications

The study has two main policy implications. Firstly, digital aid appears cheaper than cash alternatives and adds transparency. Providing a dollar of digital aid is estimated to cost 1.4 cents. Our more conservative estimated cost, which includes the costs of recruitment and facilitation is 6.7 cents. This represents a 40% savings compared to the 17 cents average costs across the World Food Programme’s cash-based transfer programmes (WFP 2023). To put the cost-savings into perspective, if in 2022, the WFP had delivered all of its $357 million in cash-based assistance digitally, the savings could have supported an additional 77,000 households or 538,075 individuals during the four-month lean season.

Additionally, policy makers have stressed transparency in digital aid deployment (ODI 2015). Digital transfers leave a trail of end-to-end transactions data. Through this, donors and humanitarian agencies gain increased transparency and operational flexibility.

Secondly, contrary to expert predictions, digital aid can be delivered without diversion and used by the tech-illiterate. We surveyed international experts explaining the intervention and the context. Respondents predicted 43% of women would use digital payments, but 99.75% actually did. They expected the local authorities to tax or divert aid from roughly 40% of the beneficiaries, but less than 2% reported any attempts. The wide variance in predictions suggests scepticism, possibly explaining reluctance to adopt high-stakes innovations. This is worsened by a lack of high-quality studies of humanitarian interventions, especially in fragile states. Digital aid has exceeded expectations in its empirically evaluated performance. It provides proof-of-concept that digital aid can be a cost-effective complement to the status quo.

In 2022, 11 conflict-affected countries, including Afghanistan, accounted for over 50% of the quarter billion people facing acute hunger and potential starvation (Food Security Information Network 2023). Our study shows that digital aid is a cost-effective, credible, and efficient way to reach vulnerable populations in fragile states. Further research on digital aid in fragile contexts could involve examining the timing and amount of digital aid, its cost-efficiency vis-à-vis cash through experimental methods, its ability to reduce risky physical contact between humanitarians and beneficiaries, and its robustness (especially to avoiding diversion) when scaled up.

References

Byrd, W (2023), “Afghanistan’s crisis requires a coherent, coordinated international response,” United States Institute of Peace.

Callen, M, M Fajardo-Steinhäuser, M G Findley, and T Ghani (2024), “Can digital aid deliver during humanitarian crises?” Working Paper.

Food Security Information Network (2023), “2023 global report on food crises.”

Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (2023), “International development in a contested world: Ending extreme poverty and tackling climate change: A white paper on international development.”

Gallup (2024), “World Happiness Report.”

Muralidharan, K, P Niehaus, and S Sukhtankar (2016), “Building state capacity: Evidence from biometric smartcards in India,” American Economic Review, 106(10): 2895–2929.

Nunn, N, and N Qian (2014), “US food aid and civil conflict,” American Economic Review, 104(6): 1630–1666.

Overseas Development Institute (2015), “Doing cash differently: How cash transfers can transform humanitarian aid.”

Suri, T, J Aker, C Batista, M Callen, T Ghani, W Jack, L Klapper, E Riley, S Schaner, and S Sukhtankar (2023), “Mobile money,” VoxDevLit, 2(2): 3.

UNICEF (2024), “Humanitarian action for children 2024 overview,” UNICEF.

UN Women (2023), “Gender alert no. 3: Out of jobs, into poverty: The impact of the ban on Afghan women working in NGOs,” UN Women.

World Food Programme (2023), “Cash-based transfers empower people while building resilience.”