Investment in amenities by large foreign companies induced by labour market competition can have persistent positive effects on local living standards

The United Fruit Company (UFCo) was one of the largest and most controversial multinational companies in history. Founded in 1899, the UFCo was engaged in the cultivation and commercialisation of tropical fruits in the so-called ‘banana republics’. During most of the 20th century, the UFCo built a profitable global business while operating in over a dozen Latin American countries (Bucheli 2005). While some commentators have admired the UFCo for organising centres of human activity with a well-organised plantation economy, the commonly accepted view of the company has blamed the UFCo of exploitative colonialism, responsible for perpetuating underdevelopment in the region. Understanding this company’s past can guide current policy debates on multinationals, large-scale foreign investments, and local economic development.

The United Fruit Company in Costa Rica

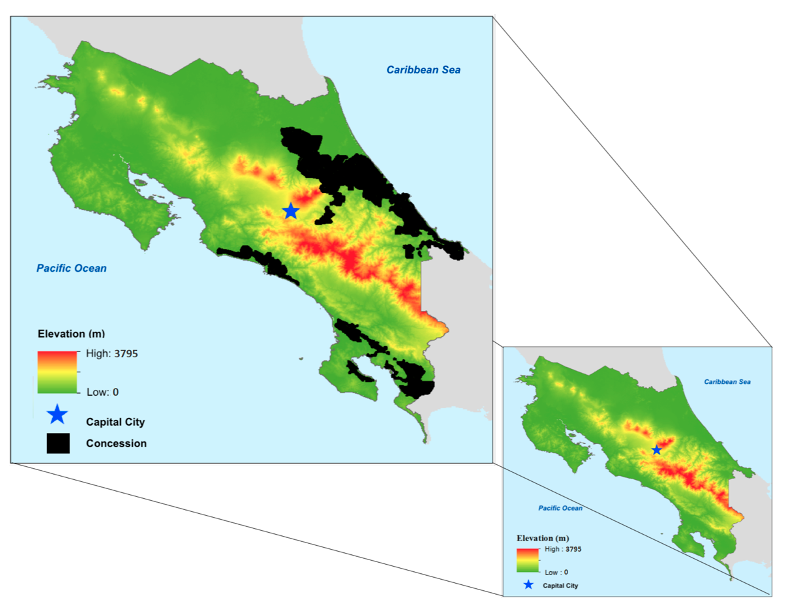

In Costa Rica, this American firm was given a large land concession, equivalent to almost 9% of the national territory (as shown in Figure 1), where it was virtually the only employer from 1899 until it left the country in 1984. Moreover, concerned about the spread of diseases like malaria and yellow fever, the firm required most of its workers to live within company lands, thereby potentially gaining more control over them (Chomsky 1996). However, our study shows that the company increased local living standards and that its effects were persistent over time.

Figure 1 Costa Rica and the UFCo's land concession

Better local living standards

The UFCo left Costa Rica in 1984. In our study (Méndez-Chacón and Van Patten 2021), we show that the UFCo had a positive and long-lasting impact on living standards in the regions where it operated. Using historical records along with detailed census data, and relying on a plausibly exogenous land assignment, we implement a geographic regression discontinuity design which shows that households living within former UFCo areas have had better economic outcomes – on measures including housing, sanitary conditions, education, and consumption – than households living in comparable locations in the country.

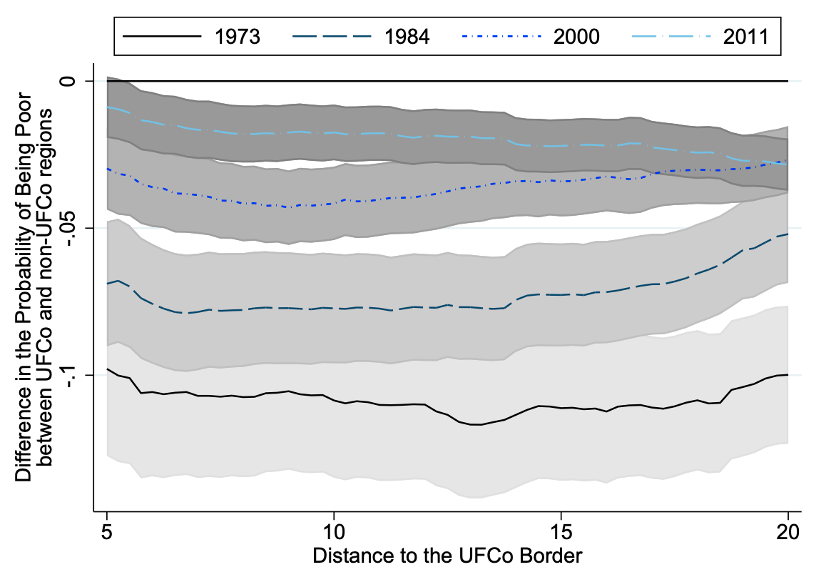

For instance, households within UFCo areas were 33% less likely to be poor in 1973 compared to those outside the UFCo area, with only 59% of this income gap closing over the following four decades. Figure 2 shows how this result holds even when conducting the analysis along UFCo’s entire border and at different distances from the boundary. It also showcases the convergence across regions over time. Moreover, satellite data shows that regions within the concession’s boundary are more luminous at night – which is associated with 6.37% higher income levels – than those outside the UFCo region, even today.

Figure 2 Difference in the probability of being poor between UFCo and Non-UFCo regions along UFCo’s entire border

Fruitful investments

Historical data hand-collected from primary sources suggests that investments in local amenities carried out by the UFCo – hospitals, schools, roads – are the main drivers behind its positive effects. For instance, investments per student and per patient in UFCo-operated schools and hospitals were significantly larger than in local schools and hospitals run by the government, and sometimes even twice as large.

Why were these investments in local amenities higher than outside the concession region? Evidence from archival company annual reports suggests that these investments were induced by the need to attract and maintain a sizable workforce, given the initially high levels of worker turnover that it faced. High turnover was the result of high competition in the labour market. For instance, the 1922 UFCo Annual Report (UFCO 1923: 75-76) contains a section highlighting the constant overturn of labour and describes that “[the workers’] migratory habits do not permit them to remain on one plantation from year to year, but as soon as they become physically efficient and acquire a little money they either return to their homes or migrate elsewhere and must be replaced by new labourers.”

While the company might have invested in hospitals to have healthier workers, making other investments, such as in schools, was identified as a solution to retain workers. The 1925 UFCo Annual Report (UFCo 1925: 185) pointed out that “an endeavour should be made to stabilise the population...We must not only build and maintain attractive and comfortable camps, but we must also provide measures for taking care of the families of married men, by furnishing them with garden facilities, schools and some forms of entertainment. In other words, we must take an interest in our people if we may hope to retain their services indefinitely.”

Empirically, we use an instrumental variables strategy to document that, among UFCo landholdings, those closest to areas where agricultural workers could earn high wages while the company was operating have a lower incidence of poverty even three decades after the UFCo left the region. This difference in economic outcomes can be attributed to higher UFCo investments to retain workers in these locations. Structurally, a model based on the UFCo’s setting and estimated on historical data shows that the company’s effect on living standards depends crucially on workers’ mobility, which was relatively high for Costa Rican workers. In fact, we show via counterfactual exercises that the UFCo would have decreased well-being had workers been half as mobile.

Conclusion

Understanding the implications of large-scale foreign investments is particularly relevant today. Just in the last two decades, foreign private investors have acquired more than 64 million acres of land via leases (of up to 99 years) or purchases of farmland for agricultural investment in the developing world (Cotula et al. 2009). The experience of the UFCo in Costa Rica highlights the crucial role of labor mobility and worker outside options in determining the effects of these projects on local living standards, and documents how persistent these effects can be over time.

References

Bucheli, M (2005), Bananas and Business: The United Fruit Company in Colombia, 1899-2000, New York University Press.

Chomsky, A (1996), West Indian Workers and the United Fruit Company in Costa Rica, 1870-1940, Louisiana State University Press.

Cotula, L, S Vermeulen, R Leonard, and J Keeley (2009), Land Grab or Development Opportunity? Agricultural Investment and International Land Deals in Africa, IIED/FAO/IFAD, London/Rome.

Méndez-Chacón, E and D Van Patten, (2021) “Multinationals, Monopsony, and Local Development: Evidence from the United Fruit Company”, Working Paper.

UFCo – United Fruit Company (1922), Medical Department Eleventh Annual Report, Boston.

UFCo (1925), Medical Department Fourteenth Annual Report, Boston.