Are flexible cash grants or earmarked grants for technical training and consulting services more suitable to boost profits, employment and survival of small firms? New evidence from Burkina Faso that directly compares both types of support shows that flexible cash grants are more effective and cheaper to implement, especially in a fragile context.

Creating new jobs is one of the biggest socio-economic challenges in low- and middle-income countries. Since a large chunk of employment is in small firms, many governments target entrepreneurship and provide support in form of training, microcredit, cash grants, individual or group advisory services, or a combination of these to enhance the creation of new jobs - so far with mixed results. In fact, most interventions fail to generate transformative effects at a large scale due to poor targeting, too little flexibility, and the limited size of the support (Cho and Honorati 2014, Grimm and Paffhausen 2015, McKenzie 2020). An unresolved policy question is whether support in form of grants should be flexible (“cash grant”) and its exact use left to the discretion of the beneficiary or whether it should be earmarked and accompanied by strict procurement rules and possibly an own contribution (“matching grant”).

The rationale for providing cash grants is to relax capital market constraints and to free up resources for investment in machines, tools, infrastructure, and inventory. This could be especially important in sectors with substantial entry barriers (De Mel et al. 2008). The assumption is that firms know best what they need and in which items to invest. In contrast, providing earmarked support assumes that firms are often unaware of the returns on various investments and that uncontrolled support may ultimately end up in inefficient investments, household consumption or even be ‘taxed’ by relatives and friends in need. This might especially be a concern in fragile countries where firm owners might be reluctant to invest in risky activities for which returns may take time to materialise (McKenzie et al. 2017). Yet prescribing support for specific inputs and actions might be seen as paternalistic and depriving entrepreneurs of their own agency, suggesting a potential suspicion that they could misuse or simply use grants dishonestly.

Comparing flexible cash grants with grants earmarked for technical training and consulting services

To shed light on that question, we conducted a randomised controlled trial (RCT) in Burkina Faso to compare 400 firms that received flexible cash grants with 400 firms that received subsidies earmarked for investments in individualised technical training and consulting services (Grimm et al. 2024). The aim of the earmarked (or “matching”) grants was to enhance innovative and risky activities such as developing new products or implementing new production processes to increase productivity. A third group of 400 firms received no support and served as a control group. All firms were selected using a business plan competition. Firms in both treatment arms could qualify for support of up to US$8000. Firms that were assigned to earmarked grants were matched with service providers and had to make an own contribution of 20% toward the total costs. The grants followed strict procurement rules, and their use was closely monitored. In contrast, cash grants could be used for any type of investment including machines, tools, livestock, construction, land, inventories, and technical and management training as well as consulting services. Cash grants came with only light procurement rules.

Firms were randomly assigned into one of the three treatment arms using a public lottery and were followed for two years after they had received their grants. The experiment was implemented in the Southeast of Burkina Faso, largely in rural or semi-urban areas. 62% of all firms were in agriculture, 25% in manufacturing, and 13% in services. 87% of all firms were already operating at baseline and 13% were planned firms. On average, the former had been in business for eight to nine years and made monthly profits of about US$500. About 40% of the owners were female. The average value of the capital stock was $3,700, about a fifth of all firms reported no capital, and firms had on average less than three employees.

The country context over the period of observation was difficult because of the COVID-19 pandemic, related workplace and border closures, an economic recession, and a steadily rising number of terrorist attacks, yet these attacks happened largely outside the study region.

If firms can choose, only few opt for technical training and consulting services

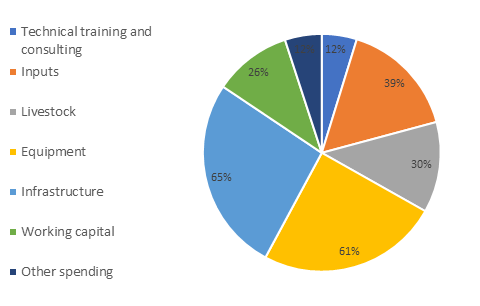

Interestingly, only 12% of all beneficiaries of cash grants chose technical training and consulting services, most of them spent their grant on capital goods, inputs, and livestock. Beneficiaries of earmarked grants used their subsidy in almost all cases on technical training, but many complemented this with general business training or, more specifically, on training in financial management and accounting, or in marketing.

Figure 1: Choices of beneficiaries of flexible cash grants

Notes: Inputs refer to the purchase of livestock used in production (for example, donkey), livestock for breeding, and other production inputs. Equipment refers to the purchase of machines, production materials etc. Infrastructure refers to the construction of a warehouse, wall, hangar, cowshed, piggery, pond, or farmland (multiple answers possible).

Impacts of grants on business outcomes in Burkina Faso

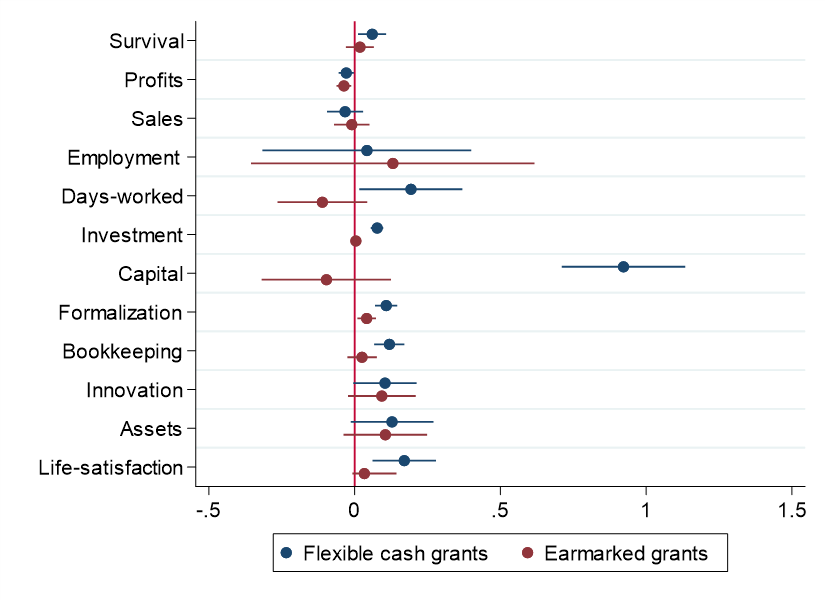

Two years after implementing the interventions, beneficiaries of cash grants showed higher survival rates, improved business practices, more formalisation, and more innovation activities compared to beneficiaries of matching grants and firms in the control group. However, neither cash nor matching grants significantly increased profits, sales, and employment relative to the control group. Only the smaller share of beneficiaries of cash grants in industry and services saw a slight increase in their profits.

Figure 2: Treatment effects of flexible cash grants and earmarked matching grants (vs. control)

Notes: Treatment effects for survival, formalization, and bookkeeping are measured in percentage point changes (if multiplied by 100). Treatment effects for profits, sales, investment, and capital are in percent (if multiplied by 100). Treatment effects for employment and days worked are measured in absolute changes. Treatments effects for motivation, assets and life-satisfaction are measured in changes of index values.

Still across almost all outcomes, beneficiaries of cash grants outperformed those receiving matching grants. The impacts of matching grants were generally small and often statistically insignificant. Unlike matching grants recipients, cash grant beneficiaries increased investment, saw greater growth in capital stocks, and were more resilient to the COVID-19 crisis, which could boost profits, sales, and employment in the longer term. We also found small positive impacts on household asset ownership and self-reported life satisfaction.

Overall, there was little evidence of fraud or misuse, even for the more flexible cash grants. Although matching grant beneficiaries appreciated the quality of training and consulting services, they complained about complex procurement rules and their need for capital.

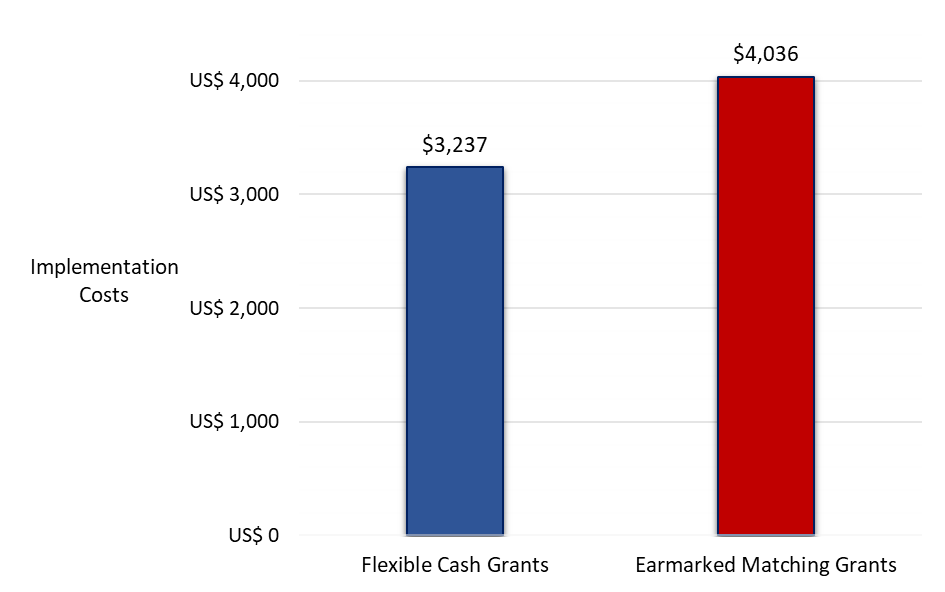

Cost-effectiveness of the flexible versus earmarked grant

On average, including the grants, the cost per beneficiary was $6,658 for cash grant recipients and $7,135 for recipients of matching grants. Excluding the grant itself, firms in the cash grant group generated costs roughly equivalent to the average grant size of $3,237. Due to stricter procurement rules, matching grants were 25% more expensive to implement, yet did not lead to better outcomes.

Figure 3: Earmarked grants are more expensive to implement

The capital stock of cash grant beneficiaries increased by about $2,500 on average over two years compared to the control group, implying a cost of $3.33 to increase the capital stock by one dollar. In context, to increase firms’ self-assessed survival chances for the coming 12 months by one percentage point would cost US$1,715. More broadly however, whether these margins are cost-effective will obviously depend on their longer-term effects on profits and employment.

Flexible grants seem to be particularly beneficial for firms in a crisis-prone and unstable business environment

The findings of the study suggest that matching grants do not seem to be able to unleash particularly risky activities with high returns. Cash grants, on the other hand, seem to be a more promising alternative, especially if survival rather than innovation is key and given that they are also cheaper to implement. Yet, the study also confirms a general lesson that many other experiments of this type have shown before, namely that increasing profits and sales sustainably and creating employment is, in general, a challenge. Yet in a fragile and unstable context, improving investment, business practices, and survival should not be underestimated. A flexible cash intervention therefore can be a worthwhile policy option in other fragile contexts with weak institutions and low-skilled workers.

References

Cho, Y, and M Honorati (2014), “Entrepreneurship programs in developing countries: A meta regression analysis,” Labour Economics, 28(C): 110–130.

Grimm, M, and A L Paffhausen (2015), “Do interventions targeted at micro-entrepreneurs and small and medium-sized firms create jobs? A systematic review of the evidence for low and middle income countries,” Labour Economics, 32: 67–85.

Grimm, M, S Soubeiga, and M Weber (2024), “Supporting small firms in a fragile context: Comparing matching and cash grants in Burkina Faso,” Journal of Development Economics, 171: 103344.

De Mel, S, D McKenzie, and C Woodruff (2008), “Returns to capital in microenterprises: Evidence from a field experiment,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(4): 1329–1372.

McKenzie, D (2020), “Small business training to improve management practices in developing countries: Reassessing the evidence for ‘training doesn’t work’,” Policy Research Working Paper Series 9408, The World Bank.

McKenzie, D, N Assaf, and A P Cusolito (2017), “The additionality impact of a matching grant programme for small firms: Experimental evidence from Yemen,” Journal of Development Effectiveness, 9(1): 1–14.