Regime stability can affect the persistence or removal of harmful practices among different traditions, including FGM and child marriage

According to the WHO, more than 200 million living women and girls have undergone some form of female genital mutilation (FGM). Researchers study FGM in order to produce effective policies for its eradication. Some studied the origins of these cultural norms (e.g. Blaydes and Platas Izama 2015, Becker 2018 for FGM or Fan and Wu 2018 for footbinding). Other try to explore what socioeconomic factors can decrease FGM rates (e.g. Shell-Duncan et al. 2011, De Cao and La Mattina 2019). However, despite accumulation of a great amount of knowledge, millions of girls are still being in danger of being circumcised in the near future.

Is there a political economy story?

Why are some harmful, supposedly out-dated cultural traditions still practiced, while others have been eradicated? Why, for instance, has footbinding in China been abolished while female genital mutilation (FGM) and the wearing of neck rings are still widely practiced in many developing countries?

While harmful practices are cultural phenomena, scholars have demonstrated that culture itself might be linked to the economy and institutions. Boyd and Richerson (1995) and Nunn (2012) describe the evolution of culture as a heuristic process. What this means, is that cultures tend to discover or learn things from themselves, implying that traditions arise because people find them beneficial. Over time, these practices become deeply held traditional values and religious beliefs (Kahneman 2011). It stands to reason that if a tradition is no longer useful, a culture should dispose of it over time, also as a part of this process.

Does this process sometimes fail?

The Dagari ethnic group was artificially divided between Burkina Faso and Ghana by the colonial administration. Despite the similarity in these countries' socioeconomic characteristics, FGM rates differ significantly on either side of the border: 87% in Burkina Faso versus 51% in Ghana.

The question arises as to why, even within the same ethnic group partitioned by a national border, some ethnolinguistic groups keep their traditions and some do not. I contend that political institutions are crucial for changing traditions and beliefs. More precisely, the stability of the political regime matters.

The importance of regime stability

The presence of a durable regime means that government policy currently being enforced against tradition is unlikely to change in the long run. People will therefore benefit from abandoning the tradition. Conversely, the presence of a weak democracy or autocracy means that the political situation is unpredictable. In this case, it is better to stay with the status quo in order to reduce uncertainty and minimise the risks of interaction between people. Similarly, in the unusual case where a regime is de facto in favour of such harmful practices (e.g. Sierra Leone in the case of FGM), the effect of regime durability will be the opposite.

In most cases, people are willing to abandon FGM, with the understanding that government will enforce its abolition: “We were asked to abandon an age-old practice, and we accepted although we were never exposed to all the disadvantages everybody is talking about.” (UNICEF 2008). Nevertheless, since FGM is a deeply held status quo tradition, it may easily reappear if there are no consistent efforts aimed at eradicating it. To encourage eradication of FGM, the government should maintain its anti-FGM activities over long periods (Mackie and LeJeune 2009).

Local populations are aware that an NGO can arrive and stay, only if a country's political regime is sufficiently stable. In countries with unstable national regimes, people revert to their traditions. A striking example is Mali, where NGO activity in numerous villages has led to a dramatic decrease in FGM rates. However, following a coup in 2012, households began to circumcise girls again. Leimbach (2014) stated that there are “side effects of the political turmoil that struck the country in 2012 and continue today, making government attempts and commitments by non-profit groups to improve conditions for women a huge struggle.”1 Therefore, regime stability affects the persistence and decay of cultural norms and traditions, through people's expectations about the enforcement of its eradication.

Partitioned ethnicities and different institutional environments

To analyse this further, I looked at data of where FGM is practised (Poyker 2019). Following Michalopoulos and Papaioannou (2014), I exploit the fact that ethnic groups in Africa were artificially partitioned by national borders. Partitioning resulted in a situation where ethnic groups with similar cultural norms and traditions were ‘randomly’ assigned to different institutional environments.

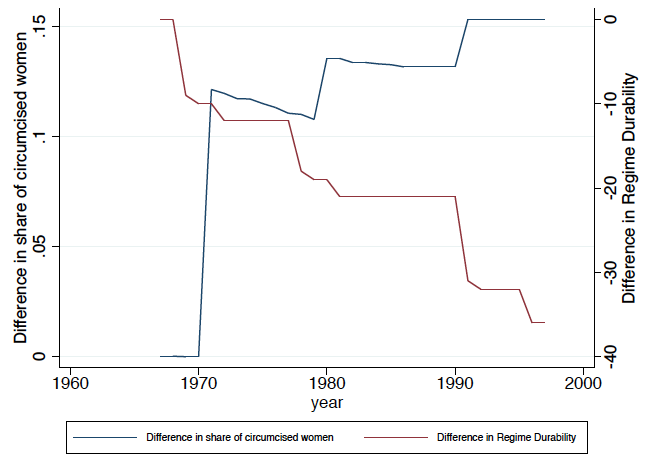

To summarise my hypothesis concerning durability of political regime and FGM rates, Figure 1 presents the FGM prevalence of the Akan ethnic group, which is divided between Ghana and Ivory Coast. Both subgroups started with similar FGM rates and the same regime durability. However, starting in 1966, Ghana experienced a period of political unrest, while Ivory Coast remained under stable authoritarian leadership. We can see that the difference in the FGM rates following shocks to regime durability, creating a situation in which FGM is more prevalent among Akan people in Ghana than among Akan people living in Ivory Coast. This case shows how ethnic groups arbitrarily divided by state borders with the same cultural norms, can change over time due to regime durability.

Figure 1

Evidence of the effect of political regime durability on FGM

I find that ethnic groups that are exposed to higher regime durability experience lower rates of FGM prevalence, conditional on the presence of an anti-FGM policy. To test the channel of the effect of regime durability, I demonstrate that it affects FGM only in an interaction with the anti-FGM policy. I also show that regime durability positively affects FGM rates in countries that de facto support FGM. This suggests that populations in durable regimes that do not conduct anti-FGM policy expect the tradition to persist and thus choose to keep the status quo.

Additionally, following Kudamatsu (2012), I show that the results hold when we compare daughters of the same mother that were subject to different regime durability at the same age. Following Jones and Olken (2005), I also document substantial increases in FGM prevalence after the death of a national leader.

Policy implications

My results suggest that a consistent anti-FGM policy from stable regimes is the key to ending FGM in developing countries. I find similar results for the tradition of child marriages suggesting that the same mechanism might work for other harmful practices as well. Traditions are malleable, but only if it the benefit from abandoning harmful practices is clear.

References

Becker, A (2018), “On the economic origins of constraints on women’s sexuality.”

Blaydes, L and M Platas Izama (2015), “Religion, patriarchy and the perpetuation of harmful social conventions: The case of female genital cutting in Egypt”, Mimeo

Caldwell, J, I Olatunji Orubuloye and P Caldwell (2000). “Female genital mutilation: Conditions of decline”, Population Research and Policy Review 19(3): 233–254.

De Cao, E and La Mattina, G, (2019), “Does maternal education decrease female genital cutting?”, AER Papers and Proceedings, 109: 100-104.

Fan, X and L Wu (2018), “The economic motives of foot-binding”.

Jones, B, and B Olken (2005), “Do leaders matter? National leadership and growth since World War II”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120(3).

Kudamatsu, M (2012), “Has democratisation reduced infant mortality in sub-Saharan Africa? Evidence From Micro Data”, Journal of the European Economic Association, 10(6): 1294–1317.

Leimbach, D (2014), “With Mali in political turmoil, high FGM rates persist.” Passblue

Mackie, G, and J LeJeune (2009), “Social dynamics of abandonment of harmful practices: A new look at the theory”, Special series on social norms and harmful practices.

Michalopoulos, S and E Papaioannou (2014), “National institutions and subnational development in Africa”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(1): 151–213.

Nunn, N (2012), “Culture and the historical process”, Economic History of Developing Regions, 27(sup1): S108–S126.

Poyker, M, (2019), “Regime stability and the persistence of traditional practices”, Columbia Business School Research Paper.

Shell-Duncan, B, K Wander, Y Hernlund and A Moreau (2011), “Dynamics of change in the practice of female genital cutting in Senegambia: Testing predictions of social convention theory”, Social Science & Medicine, 73(8): 1275–1283.

UNICEF (2008), Long-term evaluation of the Tostan Programme in Senegal: Kolda, Thies, Fatick Regions, Statistics and Monitoring Section, New York: UNICEF.

Endnotes

[1] Similarly, in Caldwell et al. (2000): ``Many mothers who continue to 'circumcise' their daughters say that they would desist if only that message were much stronger, thus guaranteeing that uncircumcised girls were in the majority. They feel that it is unfair of the government to promote change without doing it very loudly and clearly.”