Railways encouraged the growth of cities in colonial India and market access helps explain why

In 1960, one in five people in Asia lived in a city. Today, roughly half of the people in Asia live in cities (Henderson and Turner 2020). This rapid urbanisation poses several challenges, including congestion, contagion, and other issues related to density (Bryan et al. 2022). At the same time, many countries in the developing world are allocating significant resources to transportation infrastructure projects such as the ‘Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana’ highway programme in India. How are transportation infrastructure and the growth of cities in the developing world connected? Historical evidence allows us to address this question over a long time horizon.

In recent work (Fenske, Kala, and Wei 2021), we assemble a novel database on city populations in colonial South Asia. Combining these data with data on the spread of colonial railroads, we estimate the impact of railroad connectivity on city size. We use a range of complementary empirical methods, including fixed effects and an instrumental variables approach that exploits distance from least-cost paths connecting cities that predate the railroad. We find that cities that gained proximity to the railway increased in size in the period from 1881 to 1931. Market access – a measure of the connectedness of these cities to firms and consumers throughout the subcontinent – has substantial capacity to explain our results.

Urbanisation in colonial South Asia

Urbanisation in colonial South Asia – the countries that would later become Bangladesh, Burma, India, and Pakistan – was low in international comparison. Less than 10% of the population lived in towns above 5,000 persons in 1872 – a percentage surpassed in Western Europe centuries earlier (Visara and Visaria 1983, de Vries 1984). Urbanisation grew slowly, reaching 11% by 1931 (ibid.). In the colonial economy, cities were home to many small industries and almost all large industry, and were a significant source of consumer demand (Roy 2011, Tomlinson 2013). Many of the cities of South Asia that are larger today are those that were larger in 1931.

India’s colonial railways represented a significant colonial investment, spanning more than 40,000 miles by 1931 (Donaldson 2018). From 1853, railways in South Asia were built for several motives, including (Rothermund 2002, Bogart and Chaudhary 2015):

- gaining access to cotton

- unifying the colony

- responding to military threats

- preventing famine

- earning a commercial return

There is debate in the historical literature about the impacts of the colonial railways on the economy (Kuehlwein 2021, Parthasarathi 2011). More recently, economists have linked the railways to price convergence, rising agricultural income, and reduced famine risk (Andrabi and Kuehlwein 2010, Burgess and Donaldson 2010, Donaldson 2018).

Using census data to track urbanisation in India

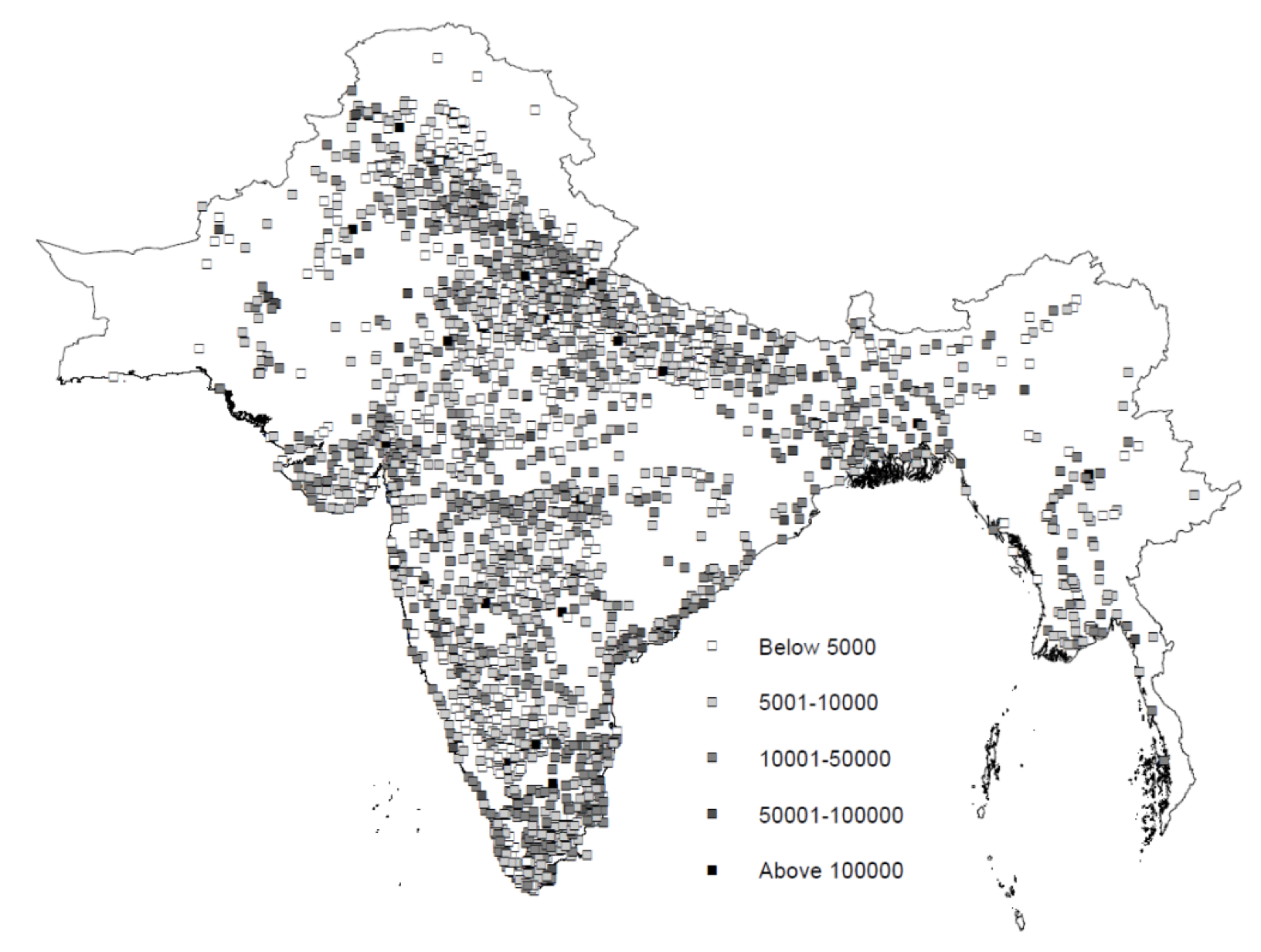

We introduce a new dataset that includes the populations and geographic coordinates of every city with at least 1,000 people in colonial South Asia. We map this during six points in time – 1881, 1891, 1901, 1911, 1921, and 1931. Our underlying source here is the 1931 census which reports retrospective city populations in census years and maps these into the districts that existed in 1931 (see figure 1). We have made these data available online. We then reconstruct shapefiles of the railway network in every census year using the 1934 edition of History of Indian Railways Constructed and In Progress.

Figure 1 City populations in 1931

Note: Baseline data is from the 1931 census which reports retrospective city populations to the districts which existed in 1931.

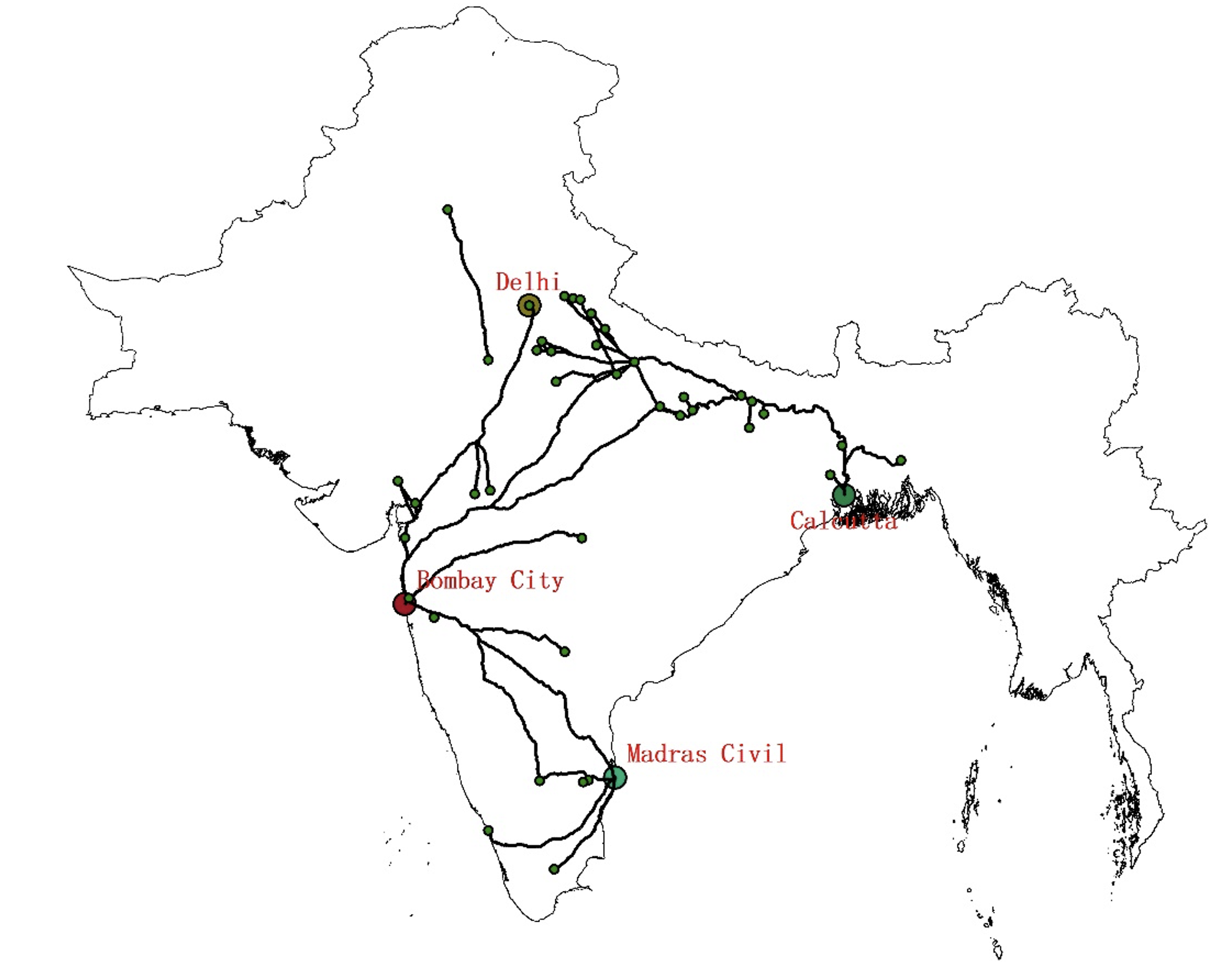

In our baseline regression estimation, we regress the log of a city’s population in a given census year on its log distance from the railway network. We also include city fixed effects and year fixed effects. We add geographic controls interacted with year fixed effects and cluster standard errors by city. To generate exogenous variation in railway placement, we follow a procedure like that in Bogart et al. (2022). This involves constructing hypothetical paths to connect large cities that predate the railway. The paths also minimise construction costs predicted by terrain slope. We use what Redding and Turner (2015) call an “inconsequential place” approach, in which we remove the nodes of these paths from the sample in order to focus on towns that were connected earlier to the railroads due to their location along a path connecting other, larger cities.

Figure 2 Least cost paths

Our baseline fixed effects estimates put the elasticity of city size with respect to distance from a railway at a modest, though not insignificant, -0.017 to -0.019. Our instrumental variables estimates are much larger, ranging from -0.113 to -0.191. Alternatively, being ‘connected’ to a railway, i.e., having a line within 2 km, raises log city size by 7.1 log points in our baseline specification. This effect is small when compared with other work in contexts such as England, Ghana, Nigeria, and Sweden (Berger and Enflo 2017, Bogart et al. 2022, Jedwab and Moradi 2016, Okoye et al. 2019). The gap between our instrumental variables and fixed effects estimates may be driven by negative selection, for example, of cities connected in famine-prone areas. The gap may also be driven by greater impacts on more isolated cities only incidentally connected by their proximity to the least cost path, or by by physical distance being only an imperfect measure of the link between railways and city size.

Market access as a measure of connectedness

This potential limitation of physical distance as a measure motivates our use of an alternative measure of railroad connectedness – market access. This is a measure of how connected a location is to other economies. In several models of economic geography, market access emerges as a sufficient statistic for the economic impact of transportation infrastructure (Donaldson and Hornbeck 2015, Eaton and Kortum 2002, Redding and Sturm 2008). With this measure, the gap between our fixed effects and instrumental estimates is much smaller. The elasticity of city size with respect to market access ranges from 0.385 - 0.628 in our fixed effects estimations to 1.028 - 1.370 using our instrument. Our results are similar when focusing on access to more distant markets.

Heterogeneous responses to railway proximity tell a similar story. It is the smallest, most initially isolated cities that grew the most in response to the railways. This implies that railways did not reinforce agglomeration. Rather, they allowed smaller cities to grow. We similarly do not find robust evidence of network externalities – cities that already had prior access to trade via medieval ports (Jha 2013) or proximity to a river do not grow more in response to railways.

Implications of transportation infrastructure on development

Our findings speak to the literatures on the economic effects of transportation infrastructure and on the long-run sources of India’s comparative development. There is a large literature on transportation infrastructure, some of which has focused on cities (e.g., Baum-Snow 2007, Baum-Snow et al. 2020), including in the past (e.g., Jedwab et al. 2017). We add evidence from a novel developing country context, using panel data spanning fifty years, in which cities are observed at several points in time, and in which we can assess the role of market access. Our smaller effects than in similar work on Africa suggest an important role for pre-rail population density and, unlike past work, we find little evidence of spillovers that reinforced the relative sizes of cities. Our results are evidence that railways did have impacts on the colonial Indian economy, including outside of the agricultural sector.

References

Andrabi, T and M Kuehlwein (2010), “Railways and price convergence in British India”, The Journal of Economic History 70(02):351–377.

Berger, T and K Enflo (2017), “Locomotives of local growth: The short-and long-term impact of railroads in Sweden”, Journal of Urban Economics 98:124–138.

Bogart, D, X You, E Alvarez, M Satchell and L Shaw-Taylor (2022), “Railways, population divergence, and structural change in 19th century England and Wales”, Journal of Urban Economics 128(103390):1–23.

Bogart, D and L Chaudhary (2015), “Railways in Colonial India: An Economic Achievement?”, in Chaudhary, L, B Gupta, T Roy and A V Swamy, (eds), A New Economic History of Colonial India, pp. 140–160.

Bryan, G, E Glaeser and N Tsivanidis (2020), “Cities in the developing world”, Annual Review of Economics 12: 273–97.

Burgess, R and D Donaldson (2010), “Can openness mitigate the effects of weather shocks? Evidence from India’s famine era”, American Economic Review 100(2): 449–53.

de Vries, J (1984), European Urbanization, 1500-1800, Routledge.

Donaldson, D (2018), “Railroads of the Raj: Estimating the impact of transportation infrastructure”, The American Economic Review 108(4-5):899–934.

Donaldson, D and R Hornbeck (2016), “Railroads and American economic growth: A “market access” approach”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 131(2):799–858

Eaton, J and S Kortum (2002), “Technology, geography, and trade”, Econometrica 70(5):1741–1779.

Fenske J, N Kala and J Wei (2021), “Railways and cities in India”, CAGE, Working Paper No. 559.

Henderson, J V and M A Turner (2020), “Urbanization in the developing world: too early or too slow?”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 34(3): 150-73.

Jedwab, R. and A Moradi (2016), “The permanent effects of transportation revolutions in poor countries: evidence from Africa”, Review of Economics and Statistics 98(2):268–284.

Jedwab, R, E Kerby and A Moradi (2017), “History, path dependence and development: Evidence from colonial railroads, settlers and cities in Kenya”, The Economic Journal 127(603):1467–1494.

Jha, S (2013), “Trade, institutions, and ethnic tolerance: Evidence from South Asia”, American Political Science Review 107(4): 806–832.

Kuehlwein, M (2021), “Railroads and Trade in 19th-Century India”, in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History.

Okoye, D, R Pongou and T Yokossi (2019), “New technology, better economy? The heterogeneous impact of colonial railroads in Nigeria”, Journal of Development Economics 140: 320–354.

Redding, S J and D M Sturm (2008), “The costs of remoteness: Evidence from German division and reunification”, The American Economic Review 98(5): 1766–97.

Redding, S J and M A Turner (2015), “Transportation costs and the spatial organization of economic activity”, Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics 5: 1339-1398.

Rothermund, D (2002), An economic history of India, Routledge.

Roy, T (2011), “Economic History of India, 1857-1947”, OUP Catalogue.

Tomlinson, B R (2013), The economy of modern India: from 1860 to the twenty-first century, Cambridge University Press.

Visaria, L and P Visaria (1983), “Population (1757-1947)”, in Kumar, D and M Desai, (eds), The Cambridge Economic History of India, Cambridge University Press, pp. 463–532.