Evidence from India shows that discussions between peers from the same majority-group that include topics involving transgender people can be effective at reducing anti-transgender discrimination.

Discrimination causes costly distortions in many economic domains – from school admissions and hiring decisions to the ability to rent a home (Hjort 2014, Hsieh et al. 2019, Christensen and Timmins 2023, Buchmann et al. 2024). It is typically considered to be hard to change, stemming from deep-seated prejudice or stereotypical negative beliefs about minorities. But sometimes societies do shift towards less discriminatory preferences: people have become more accepting of same-sex marriage, interethnic marriage, or women’s rights over the course of less than a generation. Many previous studies have examined whether such changes might be driven by social contact between a minority and a majority (Allport 1954, Rao 2019, Corno et al. 2022, Bursztyn et al. 2024). But in a world of homophily, where people mostly interact with others within their identity group, communication within the majority group may also be a powerful determinant of change.

In new research (Webb 2024), I examine whether ‘horizontal communication’ – peer-to-peer conversations among majority-group members about a minority – can affect discrimination. Why might such communication help? Perhaps through virtue signalling: if people do not want to appear to be discriminatory, they might communicate in a pro-minority manner in group settings and persuade others to discriminate less. Or perhaps who chooses to communicate in a group is important: if those who are more supportive of a minority are particularly vocal, they may persuade others to discriminate less.

I ran a field experiment in 2023 in urban Chennai in Tamil Nadu involving a sample of 3,397 individuals, examining discrimination against one of the most visible LGBTQ+ groups in India: a community of transgender women called thirunangai. This group has been historically marginalised, and they are both visually recognisable and vulnerable to extensive economic discrimination and violence.

Measuring how communication affects discrimination

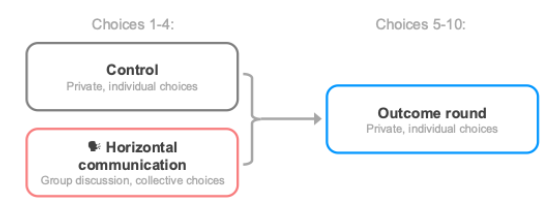

In my experiment, I measure discrimination against transgender workers by offering non-transgender participants a free grocery delivery and asking them to make a series of binary choices over which worker carries out the delivery. Participants can see photos of the potential workers and can thus discriminate against the visually recognisable transgender workers. To measure the effects of horizontal communication between participants, I randomise whether participants are earlier involved in a discussion with two of their neighbours (see Figure 1). In this discussion, participants are also shown a series of hiring options and asked to make collective choices over delivery options, including options involving transgender workers. Crucially, the only communication about transgender people in this discussion comes from the participants themselves, rather than from the discussion facilitator.

Figure 1: Experimental design

The effect of communication on discriminatory attitudes

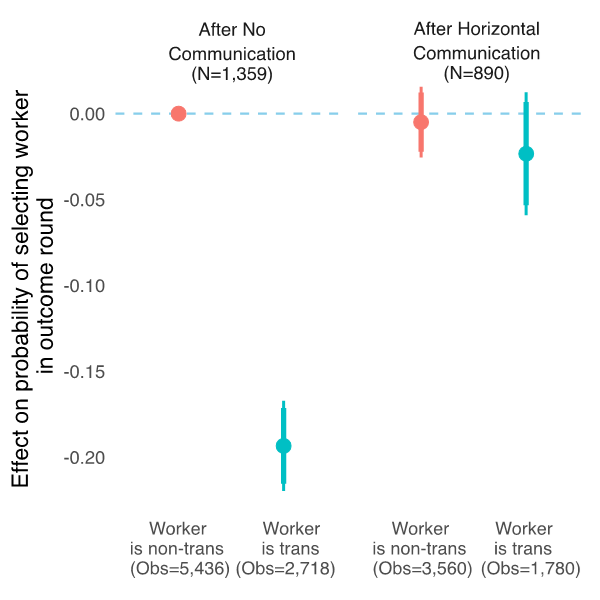

I first document that participants are highly discriminatory when making choices in private, on average. In the control group who do not engage in any communication, participants are 19 percentage points (32%) less likely to hire transgender workers than non-transgender workers (Figure 2, left panel). Their choices imply that they are willing to sacrifice grocery items worth 1.9 times the median daily food expenditure to avoid interacting with a transgender worker.

Figure 2: Effects on probability of hiring a transgender worker

Note: (i) Thick bars are 90% confidence intervals, thin bars are 95% confidence intervals. (ii) “Obs.” indicates the number of observations.

But horizontal communication between these discriminatory participants substantially reduces discrimination. The effects of the group discussion on discrimination are stark: even when people are making private, individual choices after the discussion has ended, they are 17 percentage points (42%) more likely to select a transgender worker than the control group (who were not involved in a discussion) (Figure 2, right panel). The level implies that there is no significant anti-transgender discrimination remaining, on average, in the discussion arm.

The discussion’s effects are substantially larger than a second form of communication about minorities that I test: communication about the legal rights of transgender individuals in India. I show participants a video that informs them about an Indian Supreme Court ruling that affirmed the fundamental rights of transgender persons. This reduces discrimination, but by only 59% as much as the discussion. The discussion’s effects are also partially persistent: when I re-survey participants around one month later, discussion participants are still 5 percentage points more likely to select transgender workers in a series of hypothetical hiring choices.

Mechanisms for reducing discrimination

Why do participants who are so discriminatory in private convince each other to stop discriminating, instead of just reinforcing the existing levels of discrimination? I show evidence that virtue signalling is not sufficient for explaining the effects, but persuasion is.

Virtue signalling: The results do not seem to be explained by a simple story of virtue signalling. If participants had social image concerns and did not want to appear discriminatory in a group setting, they may have acted more favourably towards transgender persons in a group setting, in turn persuading others to be more pro-transgender. I test this channel using an additional ‘public’ variation in which participants do not discuss with each other, but instead make individual hiring choices that they know will be revealed to other members of their group. This has no effect on discrimination, suggesting that participants are not trying to “show off” that they are not discriminatory.

Persuasion: By contrast, persuasion does seem to explain the effects of the discussion. To show that persuasion occurs, I add a variation in which one participant silently listens to two other people who have a discussion. The effect on these ‘listeners’ is just as large as on people who actively participate in a discussion when they make private choices after the discussion, and the effects also persist in the 1-month follow-up. People are thus being persuaded by their group to change their private behaviour towards transgender workers. But why do participants persuade each other to be more pro-transgender, rather than more anti-transgender? I show suggestive evidence that pro-transgender participants are more vocal in the discussions: they are more likely to speak first and dominate a discussion, specifically when discussing a transgender worker. They also use highly pro-social arguments that might be especially persuasive – for example, arguing that discrimination is wrong, or that transgender people should be given equal opportunity.

Leveraging the insights to reduce discrimination

Under the right conditions, horizontal communication between discriminatory individuals can substantially reduce discrimination in the short-term. I show this can occur when there are persuasive arguments against discriminating and a subset of people who are willing to speak out in favour of a minority even within a discriminatory group. While I focus on a specific setting – anti-transgender discrimination in India – further research should examine how such results apply in other contexts.

The study provides a proof-of-concept that could be applied to policies. First, we could design policies that create discussions at scale to change anti-minority attitudes. Previous work shows that one can change discriminatory attitudes by leading discussion-based interventions in schools (Dhar et al. 2022) or by door-to-door canvassing (Broockman and Kalla 2016). My results suggest that discrimination can be reduced without even having to lead a discussion; instead, just creating a scenario where minorities are naturally discussed can be sufficient.

We could also use policies that identify and amplify the voices of “positive deviants” – those who are willing to speak out against a norm of discrimination – and encourage them to persuade their peers to discriminate less. This tactic has shown promise in addressing a different harmful norm, namely, the taboo that surrounds menstruation (Macours et al. 2024) and could be applied in other settings.

A version of this article first appeared on the World Bank Development Impact Blog and Ideas for India.

References:

Allport, G W (1954), The Nature of Prejudice, Oxford, England: Addison-Wesley.

Bahar, D, B Cowgill, and J Guzman (2023), “Refugee entrepreneurship,” American Economic Association Papers Proceedings.

Buchmann, N, C Meyer, and C D Sullivan (2024), “Paternalistic discrimination,” Unpublished manuscript.

Broockman, D, and J Kalla (2016), “Durably reducing transphobia: A field experiment on door-to-door canvassing,” Science, 352(6282): 220–24. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad9713.

Bursztyn, L, T Chaney, T A Hassan, and A Rao (2024), “The immigrant next door,” American Economic Review, 114(2): 348–84. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20220376.

Christensen, P, and C Timmins (2023), “The damages and distortions from discrimination in the rental housing market,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 138(4): 2505–57. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjad029.

Clemens, M A (2021), “The fiscal effect of immigration: Reducing bias in influential estimates,” CESifo Working Paper No. 9464.

Clemens, M A, and H Hunt (2019), “The labor market effects of refugee waves: Reconciling conflicting results,” Industrial Relations Research Association, 72(4): 818–857.

Corno, L, E La Ferrara, and J Burns (2022), “Interaction, stereotypes, and performance: Evidence from South Africa,” American Economic Review, 112(12): 3848–75. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20181805.

Dhar, D, T Jain, and S Jayachandran (2022), “Reshaping adolescents’ gender attitudes: Evidence from a school-based experiment in India,” American Economic Review, 112(3): 899–927. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20201112.

Hjort, J (2014), “Ethnic divisions and production in firms,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(4): 1899–1946. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qju028.

Hsieh, C-T, E Hurst, C I Jones, and P J Klenow (2019), “The allocation of talent and U.S. economic growth,” Econometrica, 87(5): 1439–74. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA11427.

Ibáñez, A M, S V Rozo, and D Bahar (2021), “Empowering migrant women,” World Bank, Policy Research Working Paper No. 9833.

Macours, K, J Vera Rueda, and D Webb (2024), “Menstrual stigma, hygiene, and human capital: Experimental evidence from Madagascar,” Unpublished manuscript, 29 March 2024.

Rao, G (2019), “Familiarity does not breed contempt: Generosity, discrimination, and diversity in Delhi schools,” American Economic Review. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20180044.

Rozo, S, R Quintana, and A Urbina (2023), “The electoral consequences of easing the integration of forced migrants,” World Bank, Policy Research Working Paper No. 10342.

Trejo, G, and S Ley (2020), “Why cartels went to war: Subnational party alternation, the breakdown of criminal protection, and the onset of inter-cartel wars,” in Votes, Drugs, and Violence: The Political Logic of Criminal Wars in Mexico, pp. 69–112, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Webb, D (2024), "Silence to Solidarity: How Communication About a Minority Affects Discrimination," Working Paper