The caste system in India discriminates against lower-ranked castes, reducing their access to finance and dampening their entrepreneurial potential. This social norm imposes significant macroeconomic costs, ultimately impeding economic development.

A key feature of economic development is the transition from small, unproductive firms to large, efficient organisations. However, developing countries often encounter significant challenges in this regard. One major issue is the rampant misallocation of resources, which hinders productive firms from growing while allowing unproductive ones to persist, perpetuating low aggregate productivity levels (Banerjee and Duflo 2005, Restuccia and Rogerson 2008, Hsieh and Klenow 2009).

Several market-oriented distortions, such as financial frictions, labour market regulations and subsidies, among others, have been proposed as being responsible for resource misallocation. However, developing economies also feature informal institutions that may exacerbate resource misallocation by favouring certain segments of society and taking resources away from groups that could use them more efficiently. In my research (Goraya 2023), I investigate the caste system in India and document how it may hinder economic development.

The caste system in India and entrepreneurship

Caste is inherited at birth and determines one’s social identity. Historically, caste norms have restricted inter-caste interactions and promoted discrimination against lower-ranked castes while favouring higher-ranked castes. Firm creation was reserved for higher-ranked castes, while lower-ranked castes were relegated to menial tasks. Even today, these disparities persist. Although lower-ranked castes constitute around 29.5% of the population, they own less than 15% of the firms. However, the economic costs of these disparities remain unclear.

My research explores the hypothesis that "birth, not worth"—i.e. caste rather than individual productivity—determines resource allocation in the economy. The resulting economic losses from such disparities are significant on a macro scale.

Measuring firm ownership by caste in India

Using detailed microdata (Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises MSME survey of 2006-07) with information on caste of firm owners, I provide evidence that is consistent with the presence of high levels of caste-driven resource misallocation. I summarise the findings in four headline points.

The distribution of production, capital and credit across castes

At the aggregate level, firms owned by lower-ranked castes produce 8% of the total output, own 5.4% of the total capital and get 4.7% of the total credit. On the contrary, firms owned by higher-ranked castes produce 60% of the aggregate output, own 70% of the total capital and get 75% of the total credit. Two thing stands out here:

- Lower-ranked castes’ share of credit is only one-sixth of their population share.

- Lower-ranked caste firms’ output-to-credit ratio is twice as high as firms owned by higher-ranked castes.

So, why do LC-owned firm use less credit? I find that it is partly driven by lower-ranked castes’ limited access to credit.

Relative productivity and size of low-caste entrepreneurs

Firms owned by lower-ranked castes have 25-30% higher average revenue product of capital (ARPK)1 respectively, relative to firms owned by higher-ranked castes within a narrowly defined sector and region. Simultaneously, firms owned by lower-ranked castes are characterised by lower capital intensity relative to higher-ranked caste firms. A higher ARPK may represent high marginal cost of capital for firms owned by lower-ranked castes that forces them to use sub-optimally low-level of capital relative to labour.

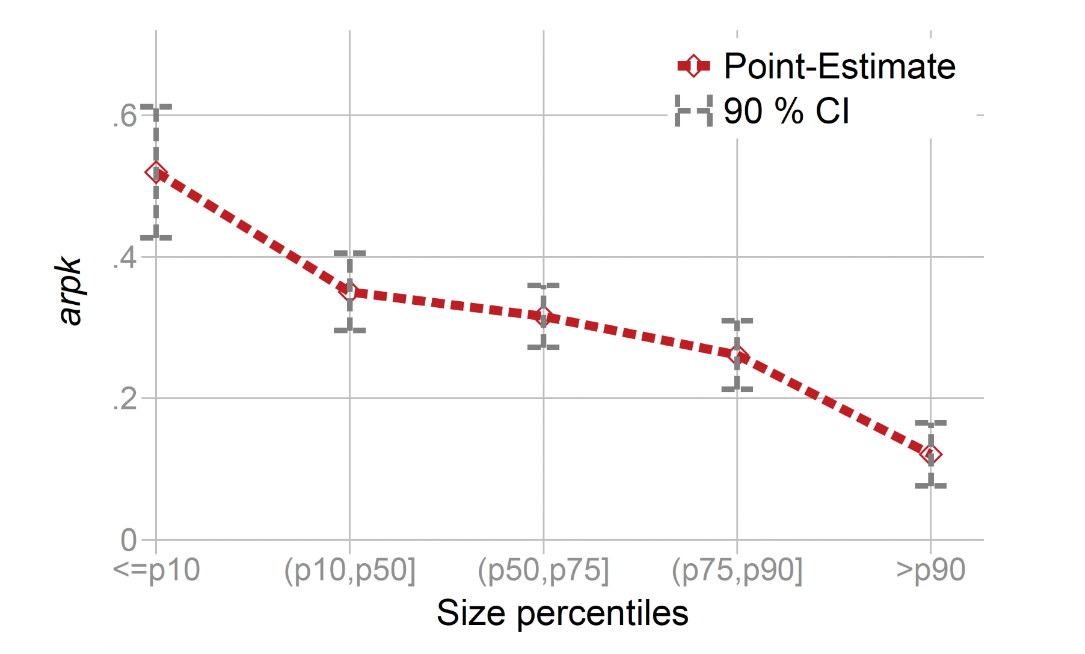

Most of the cross-caste dispersion in ARPK is driven by small firms. Moving from the smallest to the largest firms in the economy, ARPK for lower-ranked caste firms declines from being 52% higher than that of higher-ranked caste firms for the smallest entrepreneurs, to approximately 12% higher for the largest entrepreneur (see Figure 1). This finding is in line with a vast literature that finds that small firms are more likely to financially constrained than large firms.

Figure 1: The evolution of ARPK of LC-owned firms relative to HC-owned firms over enterprise size

Notes: This figures plots the evolution of ARPK of LC-owned firms relative to HC-owned firms over enterprise size. The size bins are defined as follows: (i) p10: enterprises below the 10th percentile, (ii) p10-p50: enterprises between the 10th and 50th percentile (iii) p50-p75: enterprises between the 50th and 75th percentiles, (iv) p75-p90: enterprises between the 75th and 90th percentile, and (v) p90: enterprises above the 90th percentile.

Additionally, regional financial development may affect firms owned by lower-ranked castes, as they may be more sensitive to institutional finance due to lacking access to informal credit networks. The cross-caste ARPK differences negatively correlate with regional financial development. Firms owned by lower-ranked castes have an ARPK that is double the value of firms owned by higher-ranked casted in the states with the lowest financial development (such as Bihar, Jharkhand, and Uttar Pradesh), whereas no such differences are observed in states with better-functioning financial markets.

How does caste impact access to finance in India?

I use a model of entrepreneurship where entrepreneurs face caste-specific borrowing constraints (Buera et al. 2015) to estimate the extent of caste disparities in access to credit. The estimated disparities are substantial, with financial constraints being almost twice as stringent for firms owned by lower-ranked castes relative to firms owned by higher-ranked castes. The model is able to replicate the empirical regularity that the regions with better functioning financial markets disproportionately benefits credit constrained low-ranked caste firms.

The model indicates that strict financial constraints not only impede the performance of firms owned by lower-ranked caste households but also influence their occupational choices. The lower-ranked caste households are more likely to become workers rather than entrepreneurs because they cannot scale their businesses to an optimal level, which results in lower income from entrepreneurship. Moreover, the model shows that a significant portion of the income and wealth inequality between different castes can be attributed to unequal access to finance. These borrowing constraints significantly reduce the income and wealth of lower-ranked caste households compared to higher-ranked caste households. However, within higher-ranked caste households, there is relatively much higher income and wealth inequality. This disparity arises because financial constraints disproportionately affect high-productivity individuals in lower-ranked castes (those at the right end of the productivity distribution), who are the ones more likely to establish firms. As a result, income and wealth inequality within lower-ranked castes households is suppressed.

The macroeconomic costs of caste-specific distortions

This entrepreneurship model helps me to estimate the aggregate cost of caste-specific borrowing constraints. It finds that when firms owned by lower-ranked castes have a borrowing capacity that is similar to their higher-ranked caste counterparts, the output per worker increases by 5.6%. Further, the model is used to decompose output gains at the extensive and intensive margins. At the intensive margin, the reallocation of capital from unproductive firms owned by higher-ranked castes to more productive firms owned by lower-ranked castes increases the allocative efficiency of capital in the economy; therefore, as a result, cross-caste ARPK differences fall to zero, and the overall dispersion in ARPK declines substantially. These changes result in a 3.1% rise in TFP.

At the intensive margin, the reduction in borrowing constraints induce the entry of more firms owned by lower-ranked castes as entrepreneurship is relatively more profitable when borrowing constraints are less binding. Moreover, the influx of entrepreneurs increases the demand for capital and labour. This implies an increase in the cost of productive inputs, which further leads to the exit of unproductive entrepreneurs (more likely to be wealthy and firms owned by higher-ranked castes). This improvement further increases TFP by 2.5%.

Conclusion and scope for further research on caste in India

My work suggests that the caste system in India exacerbates resource misallocation and create significant economic losses that are relevant at the macro scale. Improving access to finance for lower-ranked castes would trigger an expansion of productive firms owned by lower-ranked castes, and spur savings and wealth creation. This, in turn, would increase labour demand and create more jobs in the economy. This is particularly relevant in the case of India; where labour markets are segmented by caste lines, with 75% of employees within a firm belonging to the same caste as the owner (Goraya and Ilango 2024). Thus, to improve labour market outcomes of lower-ranked caste households, their entrepreneurial constraints need to be relaxed as well. Given the findings of this study, an important next step would be to pin down the exact reasons for low credit allocation to lower-ranked castes.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article appeared on Ideas For India.

References

Banerjee, A and E Duflo (2005), "Growth theory through the lens of development economics," in P Aghion and S Durlauf (eds.), Handbook of Economic Growth, Volume 1.

Buera, F, J Kaboski, and Y Shin (2015), "Entrepreneurship and Financial Frictions: A Macro development Perspective," Annual Review of Economics, 7(1): 409-36.

Hsieh, C and P Klenow (2009), "Misallocation and manufacturing TFP in China and India," The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(4): 1403-1448.

Goraya, S S (2023), "How does caste affect entrepreneurship? Birth versus worth," Journal of Monetary Economics, 135: 116-33.

Goraya, S S and A Ilango (2024), "Identity, Market Access, and Demand-led Diversification," Unpublished manuscript.

Restuccia, D and R Rogerson (2008), "Policy distortions and aggregate productivity with heterogeneous establishments," Review of Economic Dynamics, 11(4): 707-20.