Some families delay or abstain from cutting their daughters during a drought, but the opposite can happen too–it depends on local traditions

More than 60% of women in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), as well as many in the Middle East and Asia, undergo some type of non-medical procedure collectively called “female genital cutting” (FGC). Along with other “harmful traditional norms,” FGC can impede the socio-emotional development of girls and carry long-term health consequences (Esho 2012, Wagner 2015). In extreme cases, FGC causes serious complications during childbirth, even maternal and neonatal death (Jones et al. 1999, Banks et al. 2006), likely perpetuating poverty across generations.

FGC remains common even after countries impose legal bans. Similarly, local and international non-governmental organisations have campaigned against it for decades, but there is very little existing evidence that interventions successfully curb the practice (Novak & Bussberg 2023).

So, the practice of FGC persists, despite the high price families often pay for the procedure, legal prohibitions, pain, and potentially life-threatening health complications. This custom has persisted for hundreds or thousands of years (La Ferrara et al. 2020)—in many communities, families describe FGC as an important marker of group belonging, womanhood, and/or preparation for marriage. Our study shows that a family’s economic situation can affect their decisions to practice this long-held tradition.

In a recently published article (McGavock and Novak 2023), we show that droughts—which proxy for economic shocks in Sub-Saharan Africa—cause families to delay or even abstain from FGC for 7% of girls at risk of FGC, on average. The costliness of FGC is the most likely driver of these changes: ethnographers document that families sometimes pay for FGC with large sums of money, livestock, or portions of harvests (Shell-Duncan and Hernlund 2000, Mgbacko et al. 2010). Thus, our study provides compelling evidence that FGC decisions could be responsive to some policy lever. However, we also show that families in some ethnic groups are induced to cut their daughters in response to droughts, underscoring the importance of considering local traditions when designing interventions or policies.

How and why do droughts affect FGC decisions?

Droughts—abnormally low levels of rainfall relative to a location’s typical experience—cause poor harvests and lower household expenditure for a large share of families in SSA (Corno et al. 2020, Burke et al. 2015), where rainfed agriculture accounts for the livelihoods of nearly two-thirds of the population (FAO 2021). Since families have no control over their experience of droughts, numerous studies use their occurrence to identify the causal impact of economic shocks on various outcomes. For example, Corno et al. (2020) demonstrate that droughts increase the probability of marriage for adolescent girls in SSA–likely due to the widespread practice of brideprice, a monetary transfer from the groom’s family to the bride’s at the time of marriage.

We leverage a similar methodology. Using data from adult women who were cut before age 18, we find that droughts during their childhood caused their families to delay the FGC procedure. We estimate that droughts delay FGC for more than 2% of girls who are at risk of being cut, likely reducing myriad health complications (Shell-Duncan and Hernlund 2000, Ch. 12).

We then turn to analysing whether other families abstained from FGC altogether for their daughter as a result of a drought. For this analysis, we faced a new challenge: we first needed to identify the years in a girl’s life when her family was likely to be considering FGC. That is, since the traditional age at FGC varies substantially—with some communities cutting girls as infants and others closer to marriage—it would be misleading to examine the impact of droughts outside of the “usual” window of ages for a girl to be cut.

Ethno-local traditions affect FGC practices and the impact of droughts

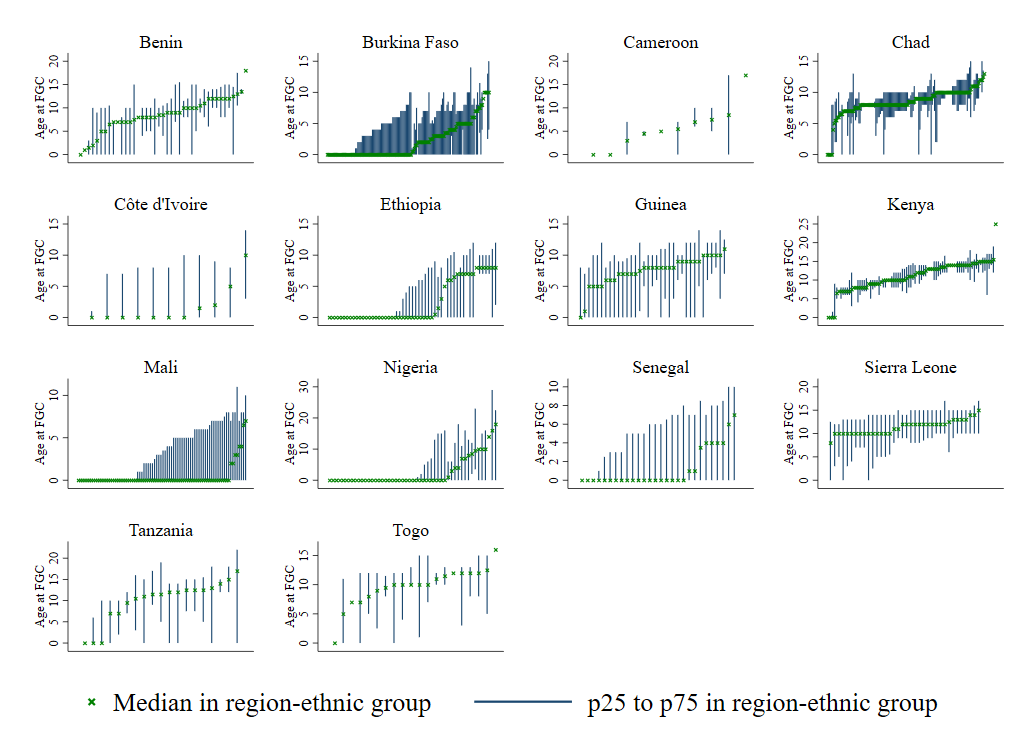

We first documented the significant variation in the age at which girls undergo FGC, both between ethnic groups as well as within ethnic groups across different communities (see Figure 1). In some cases, for example, FGC traditions vary along national boundaries among members of the same ethnic group, perhaps because some political regimes enforce bans better than others (Poyker 2023).

Figure 1: Age at FGC varies across and within ethnic groups

So, we used the members of a woman’s ethnic group who also reside within the same region to construct a reference group for each woman (where region is the first sub-national unit of geography). This helped us approximate, for each woman, a window of ages during childhood when her parents were most likely considering cutting her.

We find that, in addition to the 2.3% of girls whose families delayed FGC as a result of droughts, an additional 4.2% of girls who were at risk of FGC were never cut, preventing many potential health issues (Esho 2012, Wagner 2015, Jones et al. 1999). While these numbers may seem small, they are larger than all other estimated effects to date of what can prevent the practice of FGC, and we include statistical simulations demonstrating that our estimates are very conservative.

It is important to consider also whether ethno-local group traditions can lead to different types of impacts of droughts, depending on the age at which girls typically undergo FGC. The average impacts described thus far apply to families in groups that practice FGC at young ages (median age at FGC is 6 or younger). By contrast, families in groups with a relatively wide and older range of customary ages that are acceptable for practicing FGC are actually more likely to practice FGC when droughts occur. We hypothesise that this could be for preparing the girl for an earlier marriage in order to receive her brideprice (see Corno et al. 2020).

Policies and evaluations should be tailored to local norms and be aware of unintended consequences

FGC is costly for families, for women's health, and for society, but efforts to induce abandonment of the practice have been largely unsuccessful. Most of these interventions have focused on legal bans, which have been difficult to enforce, or programming that informs families of the risks of FGC. Our estimated effects are larger than existing results from any intervention, emphasising that a family’s economic condition affects their decision about whether and when a daughter will undergo FGC. However, the evidence base remains limited due to a lack of data on details surrounding families’ decision-making processes.

Our analysis suggests important considerations for policymakers. First, our results highlight that policymakers should carefully consider the timing of interventions. Changing parents' intentions to practice FGC may be most successful during economic downturns, when they are already considering abandonment. Further, we show that since responses to droughts differ by ethno-local norms, understanding local families’ decision-making processes is essential for policymakers and researchers evaluating interventions.

Additionally, policymakers should be cognisant of possible unintended consequences of unconditional cash transfers: they may enable otherwise resource-constrained families to practice FGC. In theory, stricter enforcement of FGC bans–or harsher monetary penalties–would make FGC costlier on average and have similar effects to droughts, but these should also be considered cautiously. Stricter enforcement could unintentionally increase health risks as families may be more likely to practice FGC in secret and/or avoid seeking medical care for health complications. On the other hand, conditioning cash transfers on delaying marriage in communities where FGC is a marriage prerequisite could also cause families to delay or even skip FGC.

Bibliography

Banks, E, O Meirik, T Farley, O Akande et al. (2006), “Female genital mutilation and obstetric outcome: WHO collaborative prospective study in six African countries.” Lancet 367(9525): 1835.

Burke, M, E Gong, and K Jones (2015), “Income shocks and HIV in Africa.” Economic Journal 125(June): 1157–1189.

Corno, L, N Hildebrandt, A Voena (2020), “Age of marriage, weather shocks, and the direction of marriage payments.” Econometrica 88 (3), 879–915.

Esho, T, E Komba, F Richard, and B Shell-Duncan (2021), “Intersections between climate change and female genital mutilation among the Maasai of Kajiado County, Kenya.” Journal of Global Health 11: 04033.

Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) (2021), “Sub-Saharan Africa: Strengthening resilience to safeguard agricultural livelihoods.” Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb8098en

Jones, H, N Diop, I Askew, and I Kabore (1999), “Female genital cutting practices in Burkina Faso and Mali and their negative health outcomes.” Studies in Family Planning 3(30): 219–230.

La Ferrara, E, L Corno, and A Voena (2020), “Female Genital Cutting and the Slave Trade,” CEPR Discussion Paper No. 15577. https://cepr.org/publications/dp15577.

McGavock, T and L Novak (2023), “Now, Later, or Never? Evidence of the effect of weather shocks on female genital cutting in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Journal of Development Economics 165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2023.103168.

Mgbako, C, M Saxena, A Cave, and N Farjad (2010), “Penetrating the silence in Sierra Leone: A blueprint for the eradication of female genital mutilation.” Harvard Human Rights Journal 23: 111.

Novak, L, C Bussberg (2023), “The Complexities of Female Genital Cutting: Understanding Maternal Influence, Stated Benefits, and Policy Design.” Working paper, Reed College.

Poyker, M (2023), “Regime Stability and the Persistence of Traditional Practices.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 105(5): 1175–1190. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_01078

Shell-Duncan, B, Y Hernlund (2000), Female Circumcision in Africa: Culture, Controversy, and Change. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Wagner, N (2015), “Female genital cutting and long-term health consequences–nationally representative estimates across 13 countries.” Journal of Development Studies 51(3), 226–246.