Sierra Leone's civil war not only left a legacy of lost lives and damaged infrastructure, but changed the way trust is formed, showing how early-life trauma can shape long-term economic decision making.

Trust underpins economic transactions, social interactions, and the overall cohesion of communities. But what happens to trust when it’s shaken by something as devastating as a civil war? Sierra Leone, a country that endured one of the most brutal civil conflicts in recent history, bears not only physical scars but psychological ones as well. These psychological legacies can impact economic decision making and we show that in our context it amplified a more cautious form of trust.

Conflict and its complex aftermath in Sierra Leone

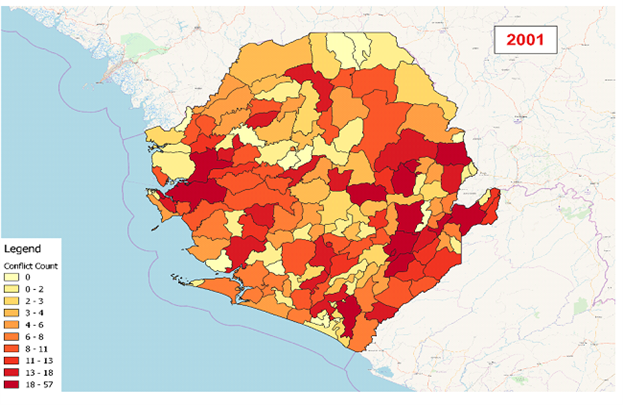

Sierra Leone’s civil war, which lasted from 1991 to 2002, was marked by indiscriminate violence and a general breakdown of social order that affected people in all parts of the country, as shown in Figure 1. In such an environment, trusting others outright may seem risky. Conventional wisdom might also suggest that war would erode trust. Our work challenges this notion.

Figure 1: Cumulative fighting intensity, by Chiefdom

We use data from nearly 4,000 young girls and women born during the Sierra Leonean civil war, whom we survey 14 years later. Alongside self-reported victimisation, we measure exposure to conflict by collecting detailed migration journals and mapping each woman to all episodes of violence that took place in the Chiefdoms in which she resided during the war. This approach can provide new and useful insights given that 46% of respondents chose not to answer questions about victimisation during the war.

How did civil war in Sierra Leone affect trust?

Our sample’s early experience with conflict has profoundly influenced how they trust others today. Instead of outright trust or distrust, the majority of these women have developed what we call conditional trust: 11% of our respondents say ‘no’ when asked if others can be trusted, 37% say ‘yes’, and 51% say ‘it depends’. The latter group is cautious, indicating that they need to know more about the other person. This can either be through:

- Fixed characteristics that signal trustworthiness.

- Malleable characteristics that suggest they are open to act cooperatively through persuasion or negotiation.

Women who resided in the direct proximity of active conflict are 7.6 percentage points more likely to opt for conditional trust, at the expense of both outright trust and distrust.

Women exposed to conflict develop higher degrees of self-efficacy

A key factor driving this shift towards conditional trust is the development of self-efficacy. In our context, self-efficacy is an individual’s belief in their ability to influence others and to steer interactions in a positive direction. The psychology literature helps explains this link through the notion of post-traumatic growth that describes a positive psychological change such as increased appreciation for life and increased perceived personal strength in the wake of highly challenging life circumstances. In short, exposure to conflict can lead, potentially through a process of post-traumatic growth, to greater self-efficacy.

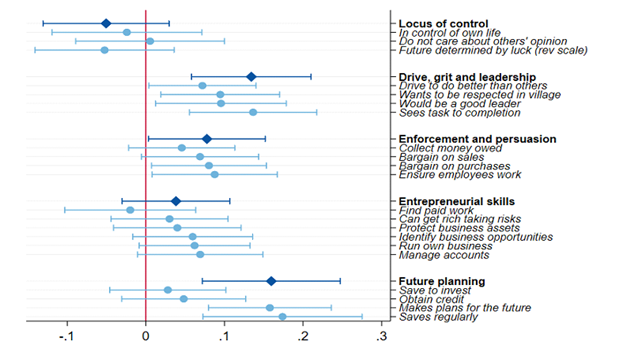

We find that women who were exposed to conflict developed higher degrees of self-efficacy on average, especially for traits connected to drive, grit and leadership and those related to enforcement and persuasion and to future planning (Figure 2). Moreover, self-efficacy directly affects conditional trust, even when controlling for conflict exposure. A one standard deviation increase in our aggregate index of self-efficacy increases conditional trust by 5.3 percentage points.

Figure 2: Exposure to conflict and self-efficacy

Note: The figure shows OLS estimates and 90% confidence intervals. These are estimated regressing indices for each sub-dimension of our self-efficacy index and separately regressing each of their components on whether the individual was ever exposed to conflict.

The influence of proximity to conflict on women’s self-efficacy

At a final stage of analysis, we explore how different experiences of conflict shape self-efficacy and hence trust preferences. Not all women in our study had the same experiences during the conflict—for example, some were directly exposed to violence, while others only heard about incidences through stories and narratives passed down by family.

Similarly high levels of self-efficacy are found among women who were in the proximity of conflict before the age when memories form and do not recall the war, likely because their parents/guardians shielded them from the narrative of these events. The group with the lowest level of self-efficacy, instead, are the socialised: those who were not in the proximity of conflict but recall victimisation, likely due to narratives being passed down to them.

This variation highlights the complexity of how conflict influences psychological development and trust formation. It also underscores the importance of considering individual experiences when designing policies for post-conflict recovery.

Implications for policy during post-conflict recovery

Our findings have important implications for how we think about the rebuilding of trust in post-conflict societies. Trust preferences are an important determinant of how our social interactions are shaped and therefore affect economic development, political stability, and social cohesion. The presence of conditional trust suggests that even in the aftermath of war, people are still open to forming connections with others—they’re just more careful about it. This finding is significant because it provides evidence of people’s psychological resilience that could be crucial for post-conflict recovery.

Moreover, understanding that trust after conflict is not necessarily binary, i.e. just to trust or not to trust, can lead to more nuanced approaches in post-conflict interventions. It is important to recognise that trust can evolve and adapt, taking on new forms that reflect the lived experiences of those who have been through trauma. These insights may be applicable in other contexts, for example, when considering behavioural responses to traumatic life events across the life cycle, such as job loss, parental loss, and violent crime.

A new perspective on the psychological legacies of conflict

The legacy of Sierra Leone’s civil war is not just one of destruction and loss. It’s also a story of resilience and adaptation. The emergence of conditional trust among women who grew up during the conflict offers a new perspective on how trust can adapt and survive in the aftermath of war. As we continue to explore the long-term effects of conflict on societies, these findings remind us that people are not merely shaped by their environments—they actively shape how they engage with the world.

References

Buehren, N, M Goldstein, I Rasul, and A Smurra (2024), “Legacies of conflict: Self-efficacy and the formation of conditional trust,” Working Paper.