A policy to pacify Rio de Janeiro’s favelas reduced murder and robbery, yet many other forms of crime increased

How does regaining control of lawless areas affect crime? In several developing countries, the absence of effective law enforcement has led to the emergence of ungoverned territories where criminal factions, including gangs and militias, have taken advantage of the situation to establish their own system of control (Blattman et al. 2022) This has resulted in a breakdown of law and order, leading to widespread insecurity and violence. While the government often believes that reasserting its physical presence is the key to resolving this issue, the impact of this approach is uncertain and could lead to either improved security or increased violence. Indeed, increasing law enforcement may incapacitate some criminals, but other mechanisms may counteract this effect. One such mechanism is the disruption of the governance previously provided by criminal gangs. In addition, changes in the overall cost of criminal activities or in the accessibility of weapons can lead to substitution effects, thereby undermining the intended impact of the policy.

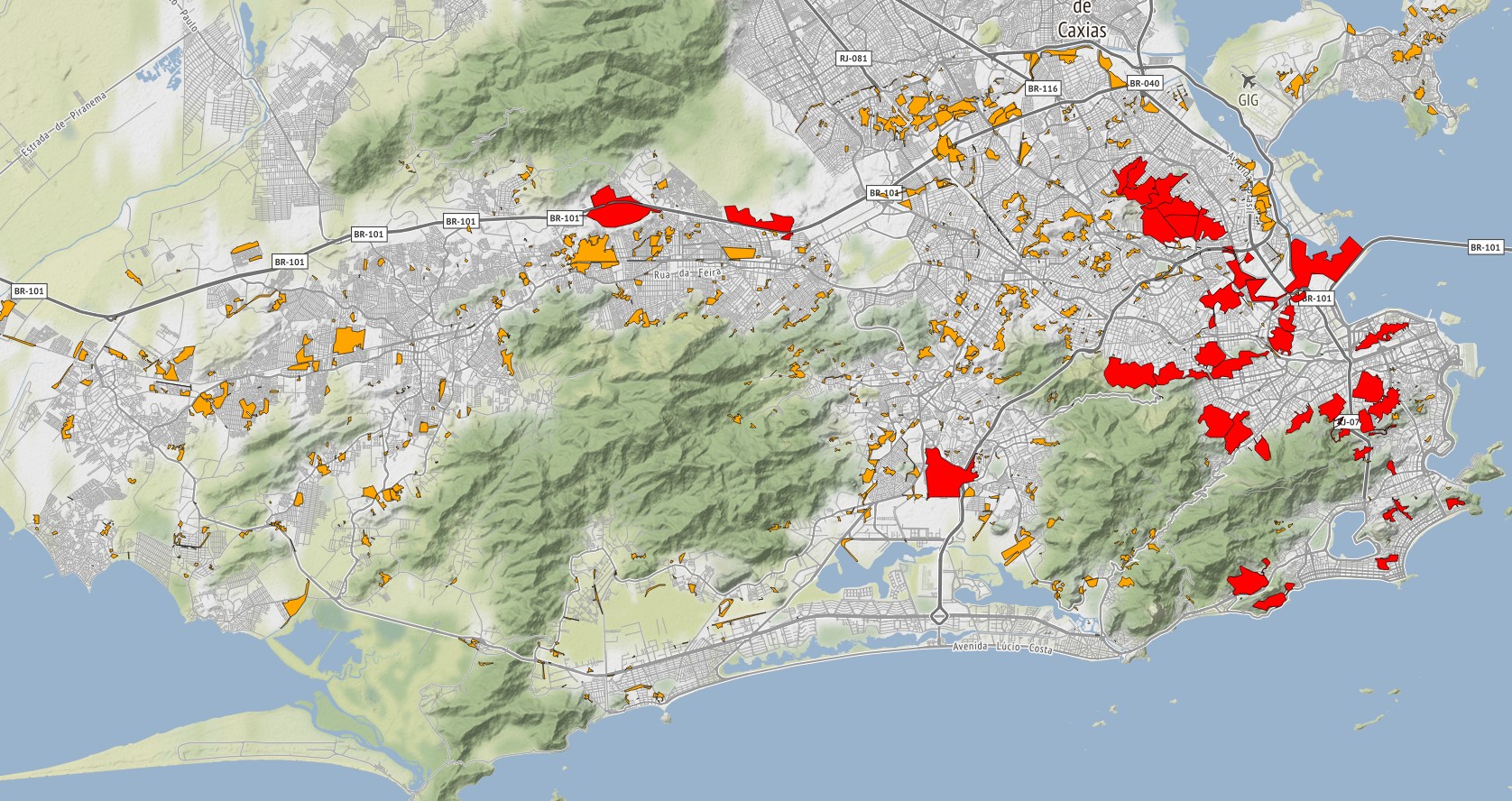

In a recent paper (Bellégo and Drouard 2023), we investigate this issue by examining the impact on crime of a pacification policy that was initiated in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro in 2008. This policy, which was progressive over time, consisted of sending a special police operations battalion (known as the BOPE) into groups of favelas to fight and drive away drug gangs, and subsequently install a new police station with a Pacifying Police Unit (UPP). By the end of 2014, 37 UPPs had been established in the city of Rio de Janeiro, covering 830 000 inhabitants (Figure 1). This major shock to law enforcement level provides an ideal setting for analysing the effects of policies fighting crime in lawless areas.

Figure 1: Location of pacified favelas covered by UPPs and other favelas in Rio de Janeiro

Notes: The figure plots the favelas in orange and the territory covered by UPPs, in red.

Mixed crime dynamics in pacified territories

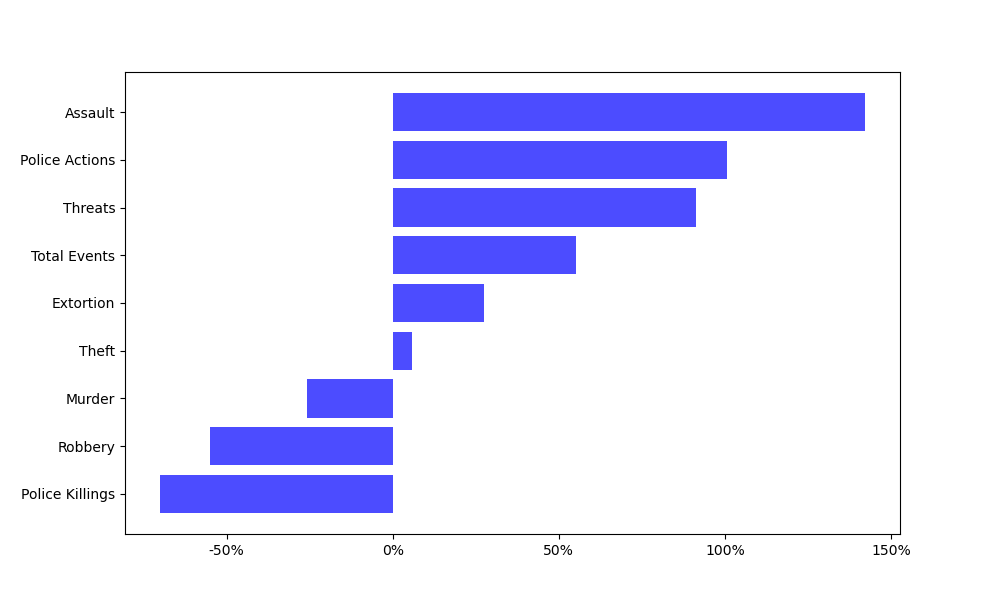

This type of policy may well have varying effects on different types of crime because the policy did not target all crimes with the same intensity and because other mechanisms leading to secondary effects may have been overlooked. Therefore, while analysing lethal violence provides some insight, it may not provide the whole picture in terms of the effects of pacification policy on crime in these areas. Descriptive statistics (Figure 2) for the different crime variables before and after pacification show a fall in the reported number of some crimes (murders, police killings and robberies) but an increase in the reported number of other crimes (assaults, thefts and threats). In addition, the total number of crimes seems to have risen sharply over the period. These descriptive statistics suggest different developments in the dynamics of crime following the pacification programme in selected favelas.

Figure 2: Percentage change in crime and police indicators before and after pacification

Notes: Percentage change in crime before (2007-2008) and after (2015-2016) pacification based on the annual mean value per 100,000 inhabitants of crime indicators obtained from monthly crime data for the favelas covered by the 37 UPPs installed in Rio de Janeiro.

The causal effect of the policy on several crime indicators

The empirical approach appeals to the geographical and time variations in the pacification of the favelas, which was progressive over time due to limited capacity and funding. The pacified areas were presumably not chosen randomly, as enforcement usually targets areas with higher crime. We therefore compare before and after crime figures in favelas that were pacified at different dates. While lethal violence is perfectly observed, pacification may lead to an increase in the reporting of non-fatal crimes by favela residents, as they may be less afraid of officially reporting a crime. Using two innovative statistical methods to correct the bias resulting from unobserved changes in crime reporting following pacification, we estimate the causal effect of the policy on different types of crime, improving our understanding of crime overall. The first method uses the number of reported accidents as a proxy for the individual reporting rate, while the second method relies on assumptions about the size of the increase in reporting.”

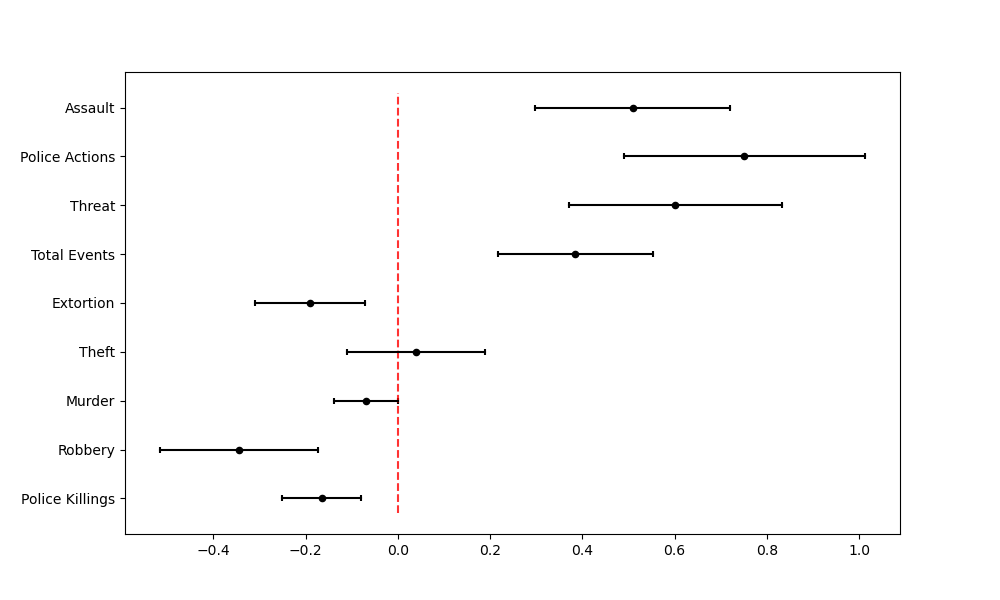

Figure 3: Estimates of the effect of pacification on crime

Notes: Estimated treatment effects and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals for various crime indicators, using regressions that controlled for UPP fixed effects, month fixed effects, and linear time trends specific to each UPP. Reporting bias was corrected using reported accidents as a proxy for the individual reporting rate for all indicators except murders, police actions, and police killings. The effects need to be exponentiated to be interpreted.

We find that pacification reduced the murder rate by 7%, while the assault rate rose by 66% (Figure 3). We also find that the number of robberies and people killed by the police fell by 29% and 15%, respectively, but that threats rose by 82%. The fact that there was a heterogenous effect of the pacification policy on different categories of crime could partly explain why the policy was not necessarily well-received by favela inhabitants (Musumeci 2017, Ribeiro and Vilarouca 2018). Indeed, while the murders were primarily targeted at gang members, the increase in less violent crime was probably felt by all residents.

The mechanisms: Gang governance and crime substitution

One clear goal of pacification was to break the control of gangs using weapons of war. By eliminating some part of the gang’s organisation and confiscating weapons in circulation, the policy should have produced a less-criminogenic environment and a general fall in crime. However, whilst certain gang-related crimes have decreased, such as murders and robberies, other offenses, including assaults and threats, have strongly increased. Two mechanisms can explain the increase in some crime indicators.

First, drug gangs that controlled favelas pre-pacification are known to provide security for their “turf” (Lessing 2012), so that driving them out could trigger a proliferation of crime unless replaced with an alternative form of security. Using differences in the style of gang governance between drug gangs, we show that pacification was indeed more harmful in areas that were controlled by a gang that was better-known for providing security to the inhabitants. This provides evidence that gang governance plays an important role in dissuading other favela residents from committing crimes.

Second, one clear objective of the policy was to remove weapons from favelas. With fewer firearms in circulation, criminals will be less well-armed and so more likely to substitute away from more violent crimes. Furthermore, in cases where there were disputes during other forms of crime, these were less likely to end up in murder. We find that weapon confiscations increased by about 50% during BOPE’s intervention to fight and drive out drug gangs, and then dropped by about 50% immediately thereafter, both relative to pre-pacification confiscations. This suggests a lower quantity of firearms in circulation after pacification. Firearm confiscations, resulting in a substitution effect between crimes, may thus at least partly explain why some crimes increase (assaults, threats) while others decrease (murders, robberies).

Policy implications

Our research highlights the challenges of implementing crime policies in lawless areas while avoiding unintended consequences. The intervention of law enforcement agencies to re-establish peace, combined with the seizing of firearms, weakens the power of local gangs and reduces the incidence of the most serious violent crimes. However, policymakers should remember not to neglect other less violent forms of crime which we show may increase in the wake of policies to wrest control of areas from criminal gangs. This is especially true given these pettier crimes can affect a larger proportion of the population.

References

Bellégo, C and J Drouard (Forthcoming), "Fighting Crime in Lawless Areas: Evidence from Slums in Rio de Janeiro", American Economic Journal: Economic Policy. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3326563

Blattman C, G Duncan, B Lessing, and S Tobon (2022), “State-building on the margin: An urban experiment in Medellín”, VoxDev, Available here.

Lessing, B (2012), "The Logic of Violence in Criminal War: Cartel - State Conflict in Mexico, Colombia, and Brazil." PhD diss. University of California, Berkeley.

Musumeci, L (2017), "UPP: Última Chamada. Visões e Expectativas Dos Moradores de Favelas Ocupadas Pela Polı́cia Militar Na Cidade Do Rio de Janeiro", Rio de Janeiro: CESeC.

Ribeiro, L and M G Vilarouca (2018) "Bad with it, worse without it: The will for continuity of the UPPs (pacifying police units) beyond the Olympics", Brazilian Journal of Public Administration 52(6): 1155–1178.